Grace

By Brian Eggert |

After two failed pregnancies and three years of trying to conceive with her husband, Madeline Matheson (Jordan Ladd) has tried everything to become pregnant. Finally, her wish has come true. She practices alternative medicine, so while she takes meticulous care of her unborn child, she also refuses to visit a hospital, despite the arguments of her overprotective mother-in-law, Vivian (Gabrielle Rose). Madeline chooses a midwife instead, for a natural birth. She has limitless love for her child, enough to will the still-born baby girl out of death and eagerly nourish its growing bloodlust.

First-time director Paul Solet wrote Grace without a hint of campy horror-movie flair. His film takes itself seriously, and it’s all the more horrific for its dedication. Shot with a next-to-nothing budget, the result moves slowly, looks grainy, but makes wonderful use of its minimalism. It’s about the powerful drive of motherly love and how easily a concerned parent can become an obsessed fanatic. The characters are described using subtle dialogue and Solet’s observant camera, and through a rather terrifying psychological progression—or perhaps breakdown is a better word—bodily horror develops as the story does, never resorting to over-the-top shocks to jolt the audience.

Consider the first scene, which depicts the baby’s conception. It’s an emotionless moment where Madeline stares off, waiting for her husband to finish so she can curl into a fertilization pose. Eight months later when her husband dies in a car accident, so does the baby, but Madeline refuses to let anyone remove the child from her womb. During her eventual birth, everyone chalks up the baby’s unexpected life to a miracle, hence naming her Grace. Madeline shuts herself off after that. She doesn’t believe in conventional doctors, and there’s a past personal gripe with her concerned midwife (Samantha Ferris), so she’s all alone with her undead baby.

Some might wonder what Grace is, some sort of zombie or vampire maybe? Why explain away some pointless detail when the real monstrosity resides in those willing to feed such a creature? The movie doesn’t ask how far a mother will go for her grotesque child (which is played by an incredibly cute baby, and occasionally a hideous rubber stand-in doll) but rather how far a mother will go to feed her own maternal instinct. Madeline clearly loves her baby, enough so that Grace’s rejection of milk and unexplained hunger for blood presents only the problem of where to find blood, whereas another parent might worry that they’ve given birth to a monster.

Crazed mothers. Madeline isn’t the only one. Her mother-in-law yearns to be a parent again, particularly after losing her son. A troubling scene involves Vivian coaxing her husband to breastfeed during sex to satisfy her own need to feel like a new mother. In a way, she’s just as disturbed as her daughter-in-law. Later she hires a doctor to persuade Madeline into a medical examination, from which he’s going to determine that she’s an unfit parent, leaving Vivian the child. When the doctor arrives, he couldn’t possibly understand what’s happening with Grace, so Madeline must protect her child. In doing so, she creates a handy source of fresh blood. How convenient.

Obvious influence comes from Roman Polanski, as Solet adopts a tone reminiscent of Rosemary’s Baby, replicating its themes of isolation, paranoia, and derangement regarding motherhood. There’s something so innocent, yet chillingly morbid, about the way Madeline asks her baby from across the room, “Are you ready for a snack?” And when she ignores the baby’s rotten smell and hangs flypaper around the crib to keep buzzing flies away, one can’t help but recall the slowly rotting uncooked rabbit from Polanski’s Repulsion. Then again, Solet’s approach to physical horror is pointedly Cronenbergian, even if his badly animated CGI flies don’t compare to the tangible makeup in The Fly. Here, the blood has a very real, squirmy, painful effect on the viewer; we cringe at the physical lengths Madeline will go to for Grace, including a number of breastfeeding scenes where it’s evident the baby wants more than milk.

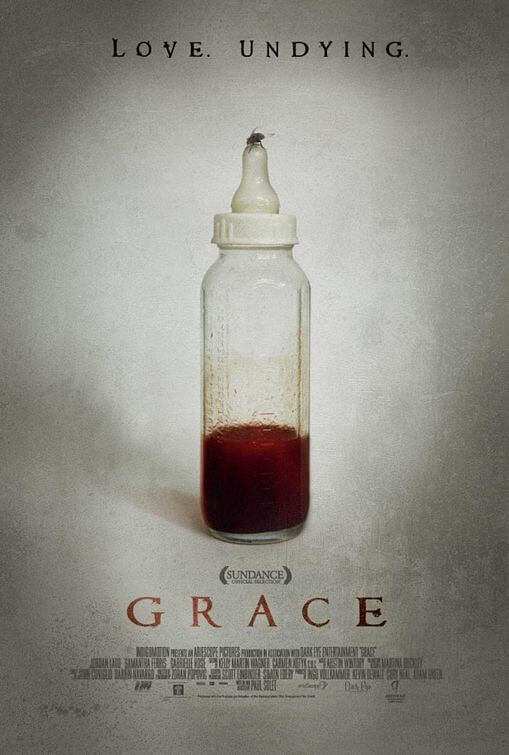

Grace, like last year’s Teeth, was screened at the Sundance Film Festival and distributed theatrically in a limited release, so it’s almost predestined to become a cult classic on-home video. Audiences shouldn’t expect typical genre tricks and cheap scares or a darkly comic satire on motherhood. At first glance, the poster or DVD cover may appear cheesy for showcasing a blood-filled baby bottle—indeed, in the hands of another filmmaker, the result might’ve been something more like Basket Case or It’s Alive. But every time Solet’s horror movie setup has an opportunity to twist into something corny, the director avoids clichés and furthers his nightmarish pitch. Its subject notwithstanding, this is an unsettling, uncomfortable, horrifying, and classy film that’s not to be missed.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review