Wall Street

By Brian Eggert |

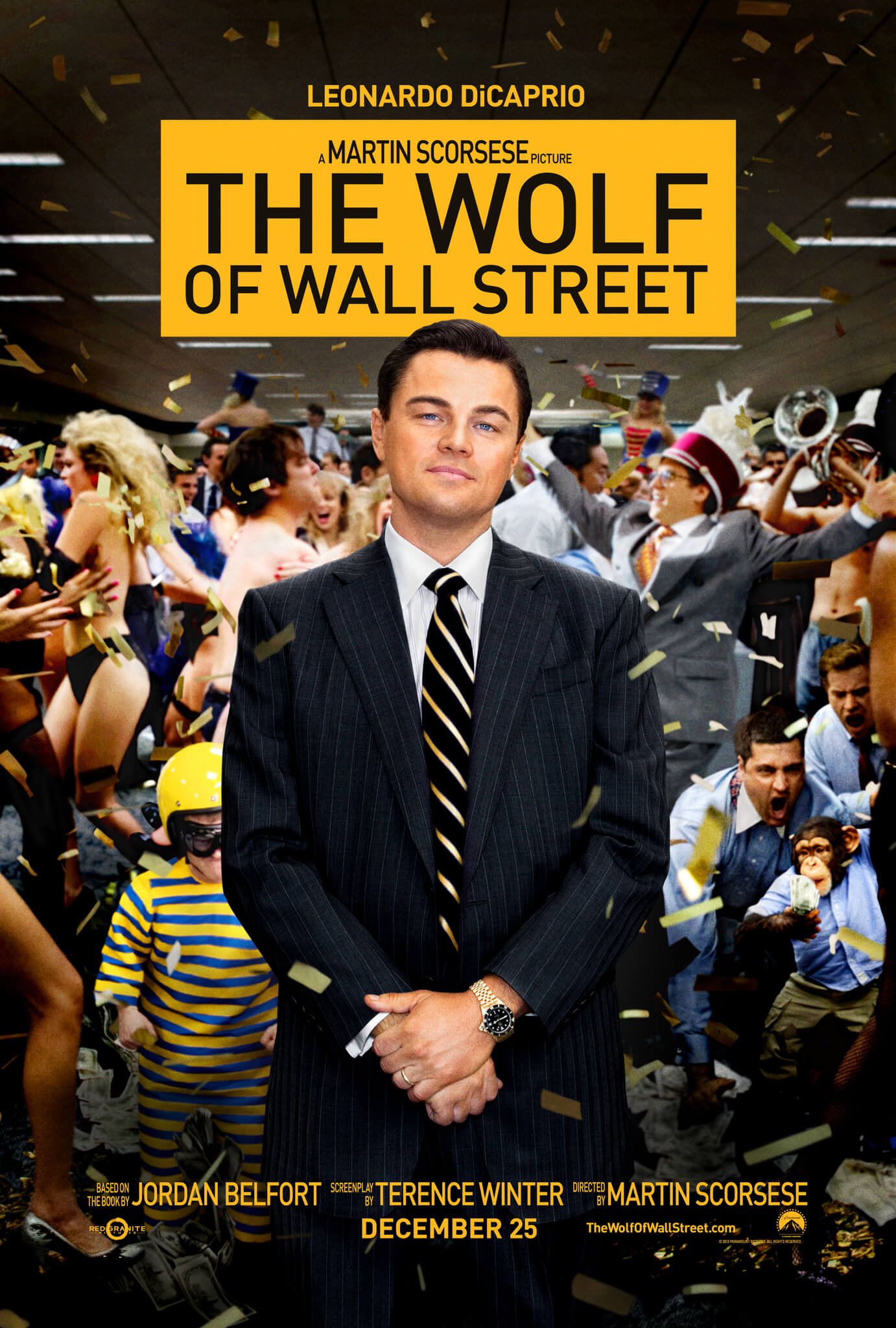

After releasing Platoon in 1986, Oliver Stone received rampant praise. It was his third attempt at directing and his second critical breakthrough after Salvador, released the same year. It earned eight Oscar nominations and won four, including awards for Best Picture and Best Director. Stone’s name was all over Hollywood; he received offers to direct from every major studio. And though he could have made bigger pictures, he chose to pursue a passion project about the world of Wall Street power brokers as a dedication to his father, an honest stockbroker years before. Stone and co-writer Stanley Weiser blasted through their eternally quotable script, originally titled Greed. And with the release of Wall Street, Stone continued with his impressive and unthinkable streak of one film per year that lasted him well into the 1990s.

When researching his subject, Stone visited stock floors and dwelled on the details of how brokers speak and the technology used. He met with actual Wall Street power brokers whose lives he discovered were filled with the excesses—the sex and parties and drugs—that would eventually be depicted in the film. Consultants such as former deputy mayor Ken Lipper and David Brown, a broker convicted of insider trading, lent the details. Still, Stone quickly realized that he was more interested in the father-son relationship at the core of his narrative. His relationship with his own father had been filled with admiration and regret; through several films, his relationship with his father served as inspiration. Thus, Wall Street became a personal project about a father-son relationship, about a boy resenting his father and searching for another father figure, only to be betrayed, bringing him closer to his birth father.

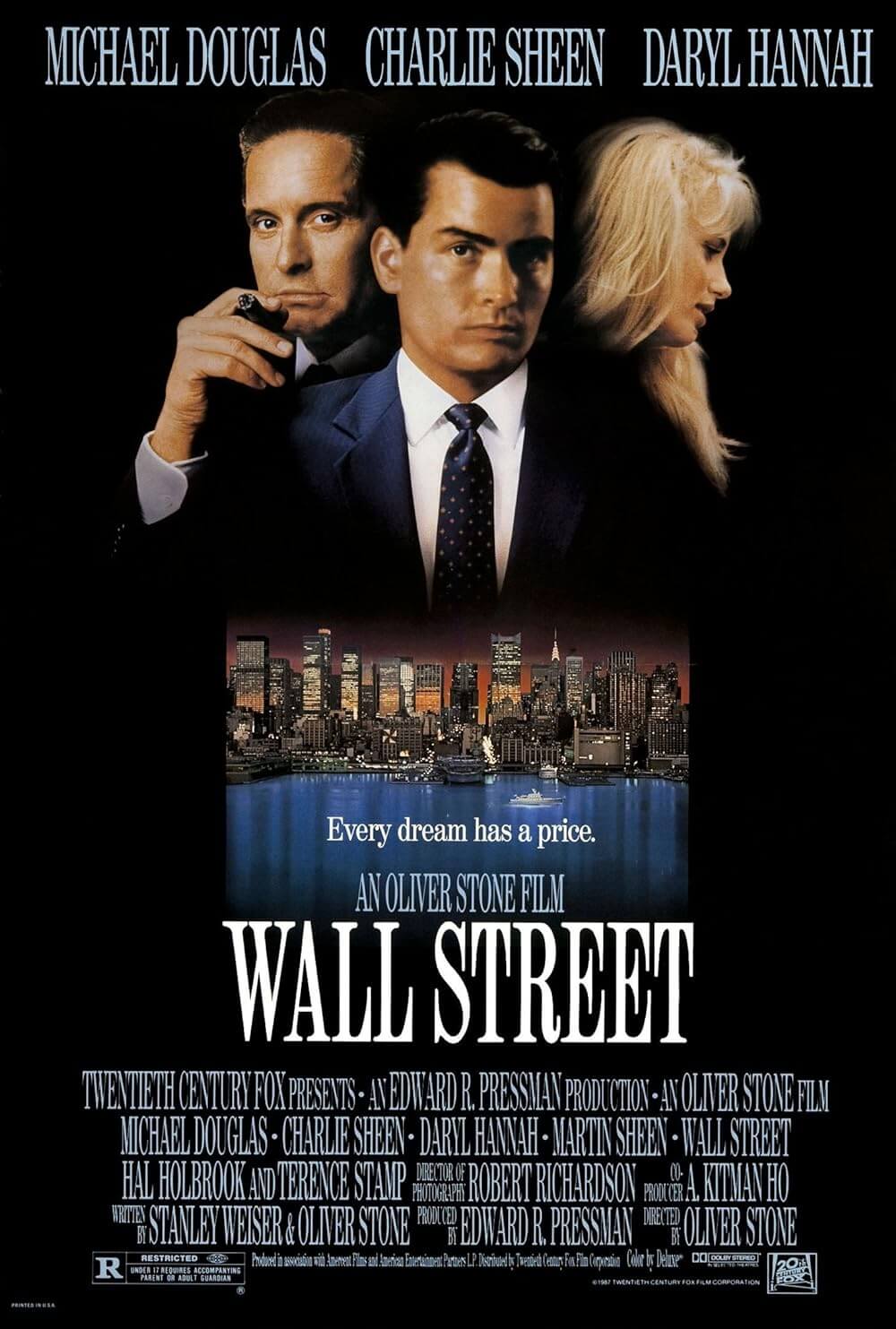

Charlie Sheen plays Bud Fox, a naïve but enthusiastic young broker who, through persistence, finagles his way into the office of Gordon Gekko, the power broker famed for moves like selling NASA stock short mere moments after the Challenger crash. Fox tries to sell Gekko on his “dog” stocks, but he sees right through them, so Fox sells Gekko on an insider tip that the airline where his father (Martin Sheen) is a mechanic will be expanding, given a recent not-yet-announced settlement payout. Information is the game, and Fox quickly becomes an info lackey for Gekko, who plays Fox with a Machiavellian spin. Meanwhile, Fox’s bank account grows. He begins dating shallow socialite interior designer Darien (Daryl Hannah). Finally, he lays down plans to help his father’s airline in a new buyout championed by Gekko. Of course, Gekko betrays Fox and plans to liquidate the airline. When Fox discovers this, he plots to manipulate the airline’s stock and drop the price to force Gekko to sell; he then convinces another moralist power broker (Terrence Stamp) to buy the airline, thus saving his father’s job.

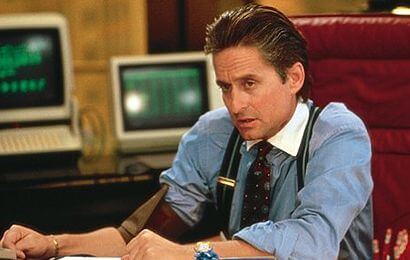

The film was budgeted for around $17.6 million, and Twentieth Century Fox picked up the bill. Costs were alleviated by tie-in and product placement deals from contributors desperate to be associated with the high-class New York City lifestyle planned for the film. Fortune magazine won a bid to place Gordon Gekko on a faux cover that could appear in the film; Carillon liquor supplied the booze; Peugeot provided the luxurious cars; Evian water quenched the thirst of the Wall Street elite; Advil cured their headaches; Motorola supplied the now absurdly large cell phones. The film was released in the wake of the 1987 market crash, so the subject was on the collective minds of Americans, earning the picture $44 million in U.S. box-office receipts. Douglas would win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance, the film’s only nomination.

As critics pointed out upon its release, there’s a slight melodramatic air that does the film a disservice next to dialogue otherwise dominated by business lingo. Stone and Weiser’s script expertly reduces complicated financial concepts to their most basic, salient form for general audience consumption. Anyone can watch the film, and though they may not follow the technical jargon, they follow the emotional core of the narrative enough to know what’s happening. Yet, at times the film sounds like an after-school special on the dangers of insider trading, with the newly corrupt Fox convincing his attorney friend (James Spader) by arguing, “Everybody’s doin’ it.” Later, in his fallout with Darien, Fox admits, “I’m lookin’ [in the mirror], and I don’t like what I see,” while she laments, “We would’ve made a good team.” This corny, pointedly ‘80s dialogue makes a serious viewing of the film suffer today, but it’s counter-acted by the bravado speeches by Douglas’ insidious Gekko.

Stone chose Michael Douglas for Gordon Gekko after Warren Beatty and Richard Gere passed. Douglas sought acting credibility after fluff roles like those in Romancing the Stone and wanted to further avoid falling into another producer-actor position. When Douglas took the part, he was attracted to the pages upon pages of monologues that would later become among the most quotable in all of cinema. He assumed the dialogue would be edited down upon filming, but Stone left the speeches intact, shockingly so. Metaphor-laden dialogue filled with violent imagery (“When I get a hold of the son of a bitch who leaked this, I’m gonna tear his eyeballs out and I’m gonna suck his fucking skull.”) transformed the financial shark character into a villainous monster. Dressed to kill in clothing based on that of real power brokers, Gekko’s pivotal scene comes when he tells his fellow Teldar Paper shareholders that he plans to restructure and ultimately “liberate” (e.g., liquidate) their company, that “Greed is good. Greed works.” Somehow, this devilish, charismatic character makes it sound like a positive thing. In his supporting role, Douglas steals the picture and remains the principal discussion point whenever the film is recalled. With the help of an Oscar, it was the performance that made Douglas into a serious actor; that year, he also released Fatal Attraction, the top-grossing film of 1987.

The other actors feel dreary in comparison to the high-energy, rapid-fire dialogue of Gordon Gekko. Charlie Sheen was hired for the acclaim he received on Platoon, though he simply wasn’t talented enough to make many of his scenes believable. But he’s watchable in the role. That’s more than can be said for Daryl Hannah, playing the epitome of ‘80s excess with profound flatness. According to set reports, Sean Young, who plays Gekko’s wife, wanted to switch roles with Hannah and became “irritating” about it, but the filmmakers wouldn’t budge. (Though, it would’ve been the right choice.) Hannah clearly doesn’t understand her role, and that kills the entire Fox-Darien subplot. But after his Best Director win at the previous year’s Oscars, perhaps Stone was too proud to admit that he had made a casting mistake.

Aside from Douglas, Stone’s most inspired casting choice was Hal Holbrook, playing the character based on Louis Stone, the director’s stockbroker father, to whom the film was dedicated. Holbrook appears onscreen with such an assured sense of morality that lines like “The main thing about money, Bud, it makes you do things you don’t want to do” feel philosophical. Whereas when Holbrook says, “Stick to the fundamentals,” the audience believes him, even if Fox doesn’t. Also giving Charlie Sheen advice was his real-life father, Martin Sheen. The scenes between the father and son Sheens contain a deep emotional truth shared by the actors. The elder Sheen’s few scenes in the film are among the very best, leading to his most crucial advice: “Create instead of living off the buying and selling of others.” This theme echoes throughout the film, condemning those like Gekko and praising those blue-collar workmen busting their hump to earn a buck. Stone has always believed in the American ideal that with hard work comes success.

Stone’s formal style of direction varies from film to film, while his themes carry over and define his work as well as his auteurist signatures. He engages powerful, complicated issues and places them into high-energy but preachy films. His sermonizing must be forgiven, however, as his films also prove incredibly entertaining and often insightful. This is the best feature of Stone’s work. For Wall Street, the director employed flat lenses, close-ups, and handheld cameras for a nonstop sense of movement, all coupled with bravado multi-frame editing sequences that impel the film’s momentum. Beyond the visual, Stone assigns electronic music largely featuring David Byrne and Brian Eno from My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and the ironic choice of the Talkingheads’ song “This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)” for a soundtrack with an enduring musical dynamism of electronic sounds and engrained beats.

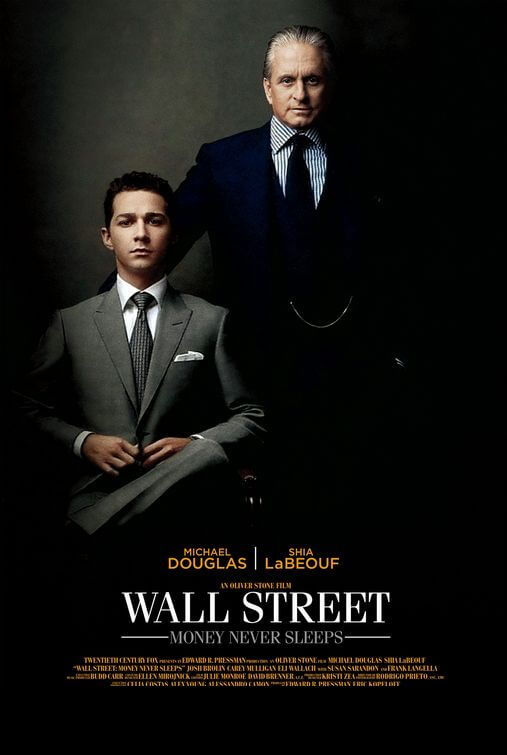

Wall Street retains an important place in film history mainly for the iconic role of Gordon Gekko and the performance by Douglas. Gekko’s mantra “Greed is Good” has become a wretched but standard staple in the business world, endlessly quoted and reflected as a signifier of 1980s business folly. (That is, until it became readily practiced and shamelessly observed in modern business.) Unfortunately, the other major actors, aside from Douglas, and occasional missteps in an overly melodramatic script, bring the film’s lasting effect down, whereas Charlie and Martin Sheen’s pairing feels inspired today. Stone’s time capsule film represents a specific period in history with incredible tangibility, communicating a complex setting with the clarity of straightforward and emotionally lucid dramatic turns. It’s an imperfect film that nonetheless has stirred audiences since its release, inspiring the occasional offshoot (see 2000’s Boiler Room) and even a sequel, and will no doubt continue to be a benchmark of fiscally minded films for years to come.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review