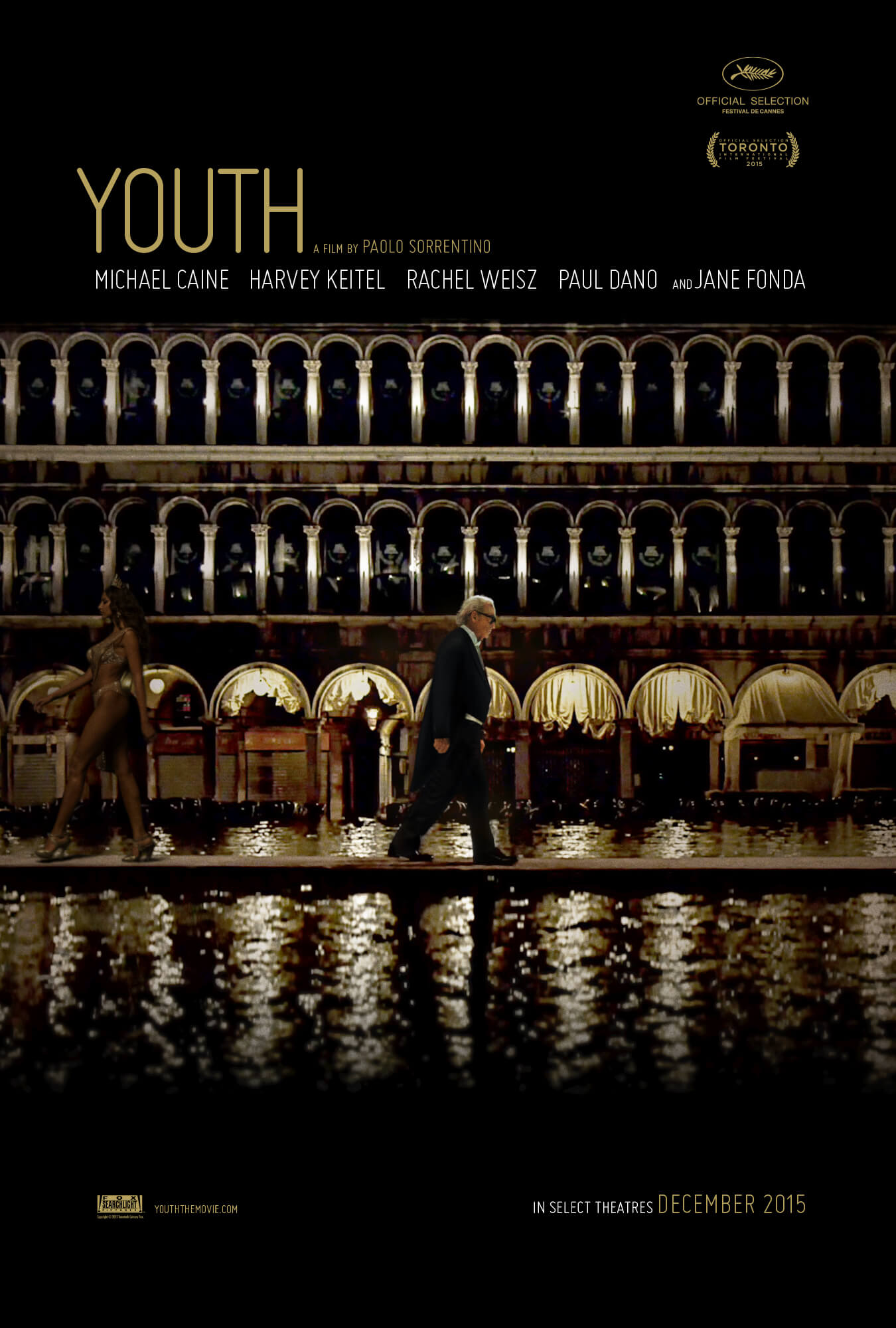

Youth

By Brian Eggert |

Wise beyond his years, Italian writer-director Paolo Sorrentino has much to say in Youth, in which he considers the relationship between the perceptions of, and relationship between, age and art. A rich assemblage of perfect scenes with less of a cohesive plot than one might desire, the film is Sorrentino’s second English-language feature after the underwhelming This Must Be the Place in 2011. Now with an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, earned for his 2013 gem The Great Beauty, Sorrentino delivers a film of no less gorgeousness or dramatic complexity. Stars Michael Caine and Harvey Keitel do their best work in years, replacing the director’s frequent collaborator Toni Servillo, offering sensitive and emotionally attuned performances in a film that has much to say through an impressive array of aural and visual beauty.

Sorrentino’s work has long been influenced by Federico Fellini, and that Italian virtuoso’s mark, specifically from 8 ½ (1963), is apparent in Youth. The film takes place at a resort spa in the Swiss Alps, where composer Fred Ballinger (Caine), along with his film director friend Mick Boyle (Keitel), has been vacationing for more than 20 years. Retired from conducting in London, New York, and Venice, he’s approached by an emissary (Alex MacQueen) for the Queen of the British Monarchy. The Queen requests that Fred conduct a performance of his “Simple Songs”, his most famous composition. Fred refuses “for personal reasons,” and also refuses to elaborate. For some time, Fred has been stricken with a debilitating case of apathy toward all things, which Caine captures in long, pensive expressions that are less apathetic than brooding.

Fred and Mick take long walks and rest in mineral pools, discussing how ineffectual their prostates are, and trying to remember missed sexual encounters from long ago. Meanwhile, Mick works on a script for his next film, pretentiously titled “Life’s Last Day”, with a group of young writers (Tom Lipinski, Chloe Pirrie, Alex Beckett, Nate Dern and Mark Gessner). Fred and Mick encounter a world-famous Hollywood actor Jimmy Tree (Paul Dano), who’s observing everyone around him for his next big role, which he hopes will shed the commercial fame from “Mr. Q”—his annoyingly popular role as a robot. And then there’s Fred’s daughter Lena (Rachel Weisz), who’s married to Mick’s son Julian (Ed Stoppard). When Julian leaves her for pop-star Paloma Faith (playing a grotesque version of herself), Lena resolves to stay at the spa as well.

Lena is a fascinating character. In one unbroken shot, Weisz shines as her character unloads on her father for his lack of presence and warmth during her childhood, and his unfaithfulness to her mother, who now rests catatonic in a hospital (an unsettling image). Her anger, spoken in somewhat routinely written dialogue, soon turns into vulnerable possibility when she meets a shy mountain climber (Robert Seethaler) at the spa. Elsewhere, Mick speaks of his new film’s impetus, the much-discussed star Brenda Morel, played by Jane Fonda, intentionally over-made-up and garish. When she arrives at the spa to confess she’s not doing Mick’s next feature, Fonda and Keitel deliver a fiery scene that has major implications on Mick. A few scenes later during a walk, he sees all of the great actresses he’s directed standing on a hill, the surreal image also striking and haunting.

As Youth carries on, Sorrentino creates a disjointed musical rhythm to the film and also delivers a number of dreamlike, undoubtedly Felliniesque sequences such as Mick’s vision. He interjects metaphoric scenes and characters, each of which could be subject to no end of interpretation. There’s a rotund vacationer at the spa, with a Carl Marx tattoo covering his back, who everyone seems to know. A masseuse (Luna Mijovic) with braces who dances in her room to a video game. Ms. Universe (Romanian model Madalina Ghenea) also shows up at the spa, outwits Jimmy Tree, and bares all to Fred and Mick. A man descends on a parachute into a cow pasture and announces, “I didn’t mean to land here!” Earlier, in that same pasture, Fred directs an orchestra of cowbells, insect buzzing, and the flapping of birds’ wings, all playing in his head, showing the composer’s enduring desire for music. And so, we must wonder, why has he withdrawn from expression?

Caine is carefully reserved in his performance, his eyes conveying an endless degree of bemused melancholy that saturates the film. Keitel is more energetic, perhaps because he’s playing an American Hollywood-type. Their roles are slyly funny yet wrought with regrets, loss of memory, and a sense of searching. Mick hopes to maintain his fading glory, while Fred looks for a reason to express himself through his chosen art. Weisz’s character seems to be in a similar rut, but she’s far younger, suggesting the film’s theme: youth is relative. With all of this philosophical exploration, there’s plenty of humor in Youth too. After all, several characters feel like caricatures and cannot help but be funny. There’s a hilarious moment when Jimmy Tree reveals he’s playing Adolf Hitler for his next role, and he enjoys his lunch in full costume, much to the alarmed stares of other spa patrons.

Even if Paloma Faith’s faux music video and some bad CGI mountain climbing scenes spoil the visual feast of Youth, Sorrentino’s cinematographer Luca Bigazzi captures no end of beautifully framed shots. Each could be framed, regardless of how much of a cliché it is to say so. David Lang’s music, from Fred’s “Simple Songs” to the less conventional music discovered in Fred’s mind, guides the film as music often does in Sorrentino’s work; there’s also a lively soundtrack featuring The Retrosettes and Ratatat. Youth is a film pouring over with details, exploring in a meditative way and looking for answers to important questions. Some viewers may get lost in the purpose of it all. Certainly, it demands much consideration afterward, examining both the emotional implications and whether the artifice supports or distracts from the narrative purpose. Whatever wisdom is gleaned from a long life, or from the perception of youth itself, Sorrentino explores it in a wonderfully acted, highly evocative film.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!