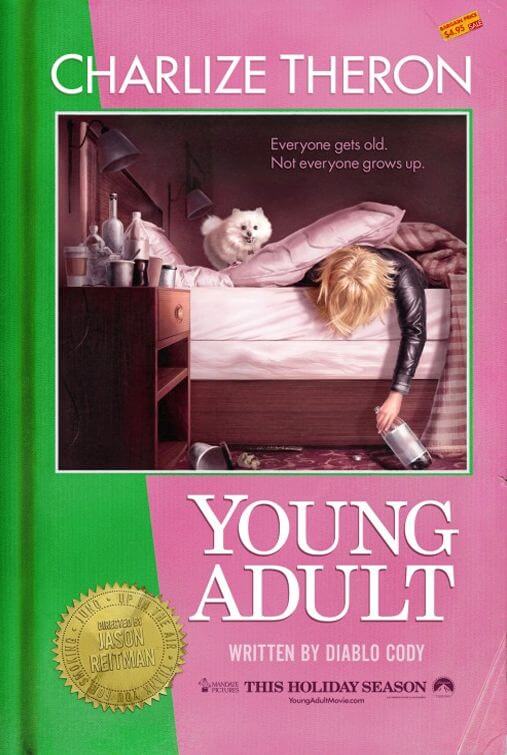

Young Adult

By Brian Eggert |

When watching Young Adult, there’s a sense that the screenplay by Diablo Cody is autobiographical, or at the very least inspired by and then exaggerated from Cody’s real-life experiences—in the same way that Megan Fox’s demon in the flop Jennifer’s Body feels like she was based on someone Cody once knew. Both films concern a contemptible popular-girl diva, driven by her social superiority and disdain for everyone “beneath” her. We all knew someone like that back in school, but Cody’s experiences must have been particularly rotten, as most of her output involves a haughty high-school princess. This time around, the Queen Bee has been out of school for more than a decade but still considers those days life-defining. She’s a petty, pathetic, obsessed, and unlikable figure, fixated on her past and unable to move on, and she doesn’t change much through the course of the film. As a result, the film isn’t very pleasant. Not that pleasantness is required.

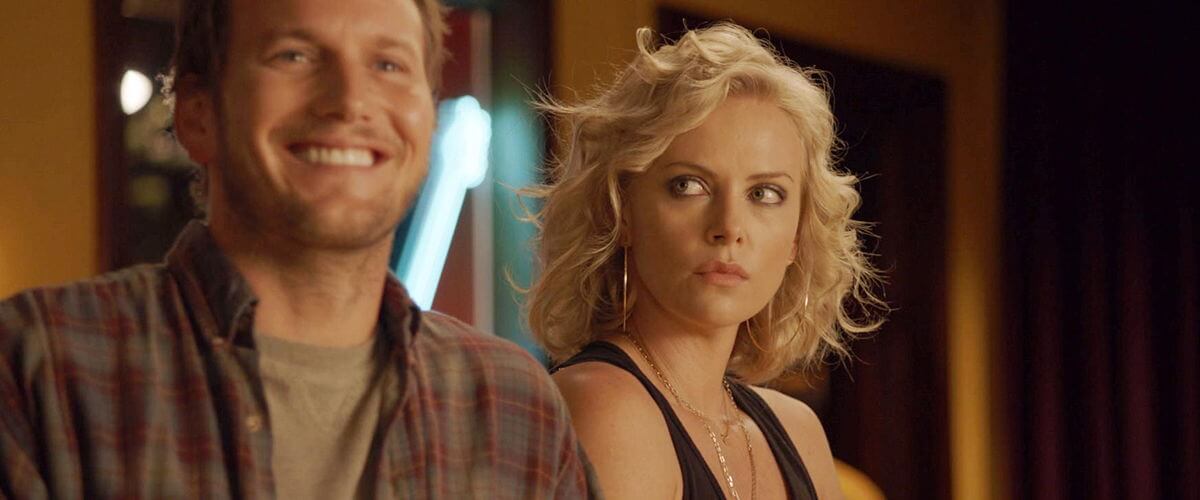

Cody reteams with director Jason Reitman, presumably to recapture the magic their collaboration spawned with Juno, but in a film that has none of the lovable characters or wit of their previous outing. In her too-cool-for-school Oscar-winning script, with its post-Tarantino use of pop-culture references and hipster slang, there was sympathy for its likable characters, particularly Ellen Page’s titular one. Here, Cody and Reitman’s black-as-pitch comedy dwells on a despicable character and attempts to make us feel something between sympathy and pity for her. But their efforts are never quite successful because she refuses to change. Charlize Theron gives an admirable performance as Mavis Gary, a Minneapolis woman in her thirties who was the prettiest, most popular girl in her rural town of Mercury, MN. Now, she’s divorced, almost certainly an alcoholic, and in denial that her career as a ghostwriter for a teen book series is failing.

One day, she receives an email from her long-lost high-school sweetheart inviting her home to Mercury for his baby’s naming ceremony. Her former heartthrob, Buddy Slade (Patrick Wilson), is happily married, but Mavis fixates on the meaningless email, interpreting it as Buddy’s cry for help. She resolves to drive to Mercury and rescue Buddy from his marriage, because, you know, she and Buddy “were meant to be”. As for Buddy’s wife and newborn baby, they’re mere obstacles to overcome. Arriving in Mercury, she goes barhopping and drunkenly explains her plot to rekindle her old flame to a local named Matt (Patton Oswalt), a former schoolmate who was beaten in high school for being gay (which he is not) and, as a result, walks on a crutch to this day. Matt tells her she’s crazy. And crazy Mavis remains, as she makes a fool of herself trying to exact her high-school-brand supremacy over people who have long since moved on. Buddy’s wife Beth (Elizabeth Reaser), for example, behaves with painful-to-watch politeness even during the film’s eventual blowup scene, where Mavis calls everyone at the Slade ceremony pathetic, and worse.

When Young Adult was over, I wasn’t sure if the audience was supposed to feel for Mavis (since the film’s climax reveals that she’s even more damaged and tragic than we thought), or if this story was just a character study of a post-high school type. Either way, I didn’t feel for her, because even after her regret becomes evident, she doesn’t try to improve herself. Mavis remains the whacked-out egomaniac whose incredible opinion of herself makes her feel entitled to a better life in “Mini Apple.” Cody infuses many such types in her script, among them Buddy, the former all-star jock who has become a humble salesman and family man. The vilest distortion is Matt, who was already a cliché when he’s shown making homemade action figures and dropping Star Wars references, but he becomes even more humbled on his crutch. Cody doesn’t enhance these familiar tropes or consider them with new insights; she just puts her flair on them, which is not enough to make them interesting.

One cannot help but notice similarities between Cody and Mavis. Both write endlessly about high school, dwelling on the past, and seem incapable of moving forward. Maybe Cody’s assessment of Mavis is a declaration of self-hatred, or maybe self-examination. Certainly, a viewer walks away from the film with a sense that Cody is more interested in writing about herself than her characters. But perhaps I’m being unfair. Admittedly, I find Cody’s celebrity insufferable, her insistence on writing about high school tedious. Screenwriters don’t normally get as much attention as she does, even after winning an Oscar. Perhaps that’s because they’re usually husky men with beards and glasses, and they don’t have the typical look for magazine covers. Cody’s celebrity persists because, in addition to her talent, the media seems morbidly obsessed with her admirably unapologetic past. In any case, the question remains: Will Cody ever move on from her own “young adult” fiction in film? As much as this film tries to be a mature, adult story, it’s still about teendom and high-school hangups.

Mind you, my views on Diablo Cody and Young Adult are not to suggest that Cody doesn’t have a lot of talent; she’s a gifted writer, but one whose public persona informs her writing all too well. Nor should this review suggest that every unpleasant character in the movies must redeem themselves. Then again, Reitman’s films usually do feature a disgraceful protagonist who learns their lesson by the conclusion—Aaron Eckhart’s pro-smoking lobbyist changes his ways in Thank You for Smoking; George Clooney’s firing expert determines to reexamine his priorities in Up in the Air—so perhaps unconsciously I was expecting that. But after a revelatory climax like the one Cody offers at the end of Young Adult, it seems strange and irregular that Mavis doesn’t grow up, not even a little. Is that the joke? If so, I didn’t think it was funny, just pathetic. And because Mavis remains such a despicable person throughout, I failed to see why I endured that time with her.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review