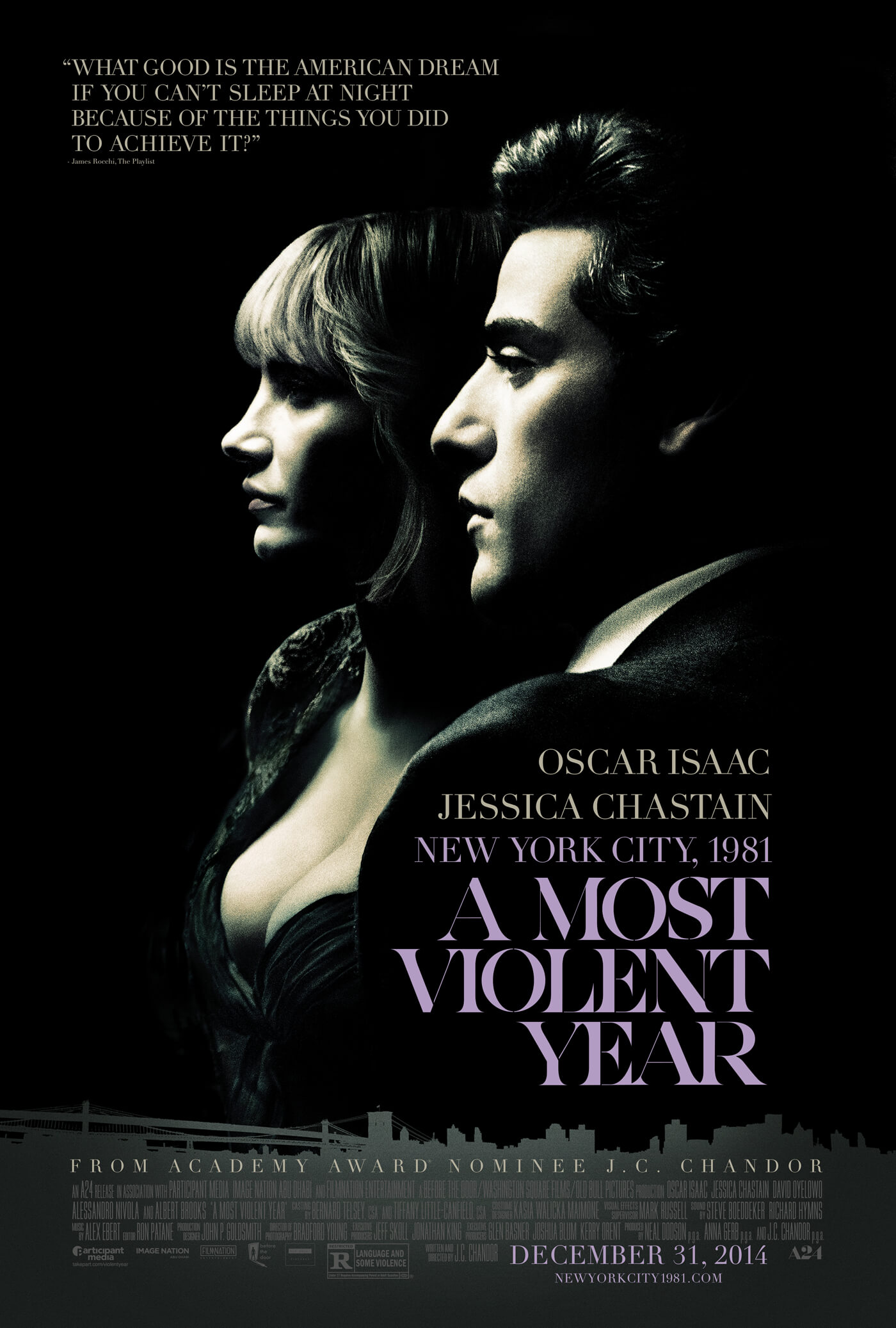

The Family

By Brian Eggert |

Unchecked idiosyncrasies and a wavering tone prevail in The Family, the Mafioso dark comedy which boasts impressive talent like Robert De Niro, Tommy Lee Jones, and Michelle Pfeiffer, but can’t find any suitable way of putting them to good use. Based on the book Malavita by French novelist Tonino Benacquista, the film was helmed by director Luc Besson, who peaked back in 1994 with Léon: The Professional and has been a prolific action producer of titles like The Transporter and Taken ever since. Besson and his co-writer Michael Caleo barely explore a multi-faceted storyline worthy of an involved Sopranos-like television series (Caleo wrote one episode of The Sopranos back in 2004), and so few of the characters receive their due consideration. Disappointingly, Besson would rather use his promising cast and setup to push one-note humor and wacky violence—an all-too-easy solution to otherwise complicated situations and characters.

De Niro plays Giovanni Manzoni, a former New York City mobster-turned-FBI informant. Along with his family—wife Maggie (Pfeiffer), teenage son Warren (John D’Leo), and teen daughter Belle (Dianna Agron)—he’s been moving around France in the Witness Protection Program for years under the guidance of Agent Quintiliani (Tommy Lee Jones). Their newest home is in Normandy, the most recent in a long line of failed relocations stemming from Giovanni’s proclivity for uncontrollable violent outbursts. The film’s structure is tangential, each family member veering off into their own subplot: Much to the chagrin of Quintiliani, Giovanni begins to write his memoirs and combat the local Powers That Be about the quality of his brown tap water, all while trying to curb his temper. Maggie wants to atone for her family’s sins and looks for absolution in France’s historic churches. Taking after his father, Warren quickly involves himself in bribery, protection, and racketeering at his high school. Belle falls madly in love with her distracted math teacher, as she believes finding love is the only way she’ll be free of her ever-moving family.

At times, the structure is used as an excuse to discuss the contrasts between Besson’s extreme versions of American and French sensibilities. The Manzoni’s are larger-than-life characterizations who embrace their hamburger-eating, Coke-drinking Americanism, whereas the French (who, of course, speak English almost exclusively) are represented as snooty and overtly bureaucratic. Giovanni then becomes the American hero who steps in to deliver severe, bloody, unfunny beatings to Frenchmen who “deserve it” (a lazy plumber, a disinterested executive). And in the rare instance where Giovanni resists his urge for violence, Besson allows the character to express his urges anyway by taking us inside the character’s head via dream sequences. Ultra-violent behavior isn’t reserved exclusively for Giovanni; however, Maggie blows up a grocery store, Warren orchestrates the trouncing of a bully, and Belle thrashes one classmate in the restroom with her fists and another in the park with a tennis racket.

Rather than follow these quietly humorous and involving storylines to any kind of substantial dramatic conclusion, Besson kills away the film’s conflicts with mind-numbing violence and rolls the credits before we have time to assess what’s happened. The finale comes when a Mafia assassin arrives in Normandy with his crew for a deadly shootout, and since violence is all these people know, the film’s conflicts can be resolved no other way. The overall mixture of two parts dark comedy, one part mob violence has undeniable roots in Married to the Mob (in which Pfeiffer starred), Analyze This (in which De Niro starred), and, as referenced above, The Sopranos. But the film’s obvious derivations lead to an excruciating meta-moment when Giovanni attends a screening of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. (Note: The English-language title for Benacquista’s book is Badfellas). Like much of the film’s humor, this self-referential scene falls painfully flat.

The Family mishandles almost every attempt at humor and tries to make a lovable, “Tony Soprano Lite” character out of Giovanni, except the paterfamilias is far too mean-spirited to win us over. Besson never masters his bad taste balancing act of R-rated violence and cheeky fish-out-water humor, resulting in the film’s off-putting shifts in tone and several missed comic beats. One moment we’re expected to laugh about Goodfellas star Robert De Niro watching the very film in which he appeared, the next moment, we’re shocked to see a suicide attempt and the threat of rape. Such shifts in tone are jarring and simply don’t play well on our viewership palate. The acting is equally unbalanced; although De Niro and especially Pfeiffer seem comfortable playing characters they’ve played before, Jones looks tired and bored in his paycheck role. Though, on a technical level, Besson’s production is admirable and assembled professionally, the storytelling is more about setting up possibilities than realizing them.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review