Reader's Choice

The Fall

By Brian Eggert |

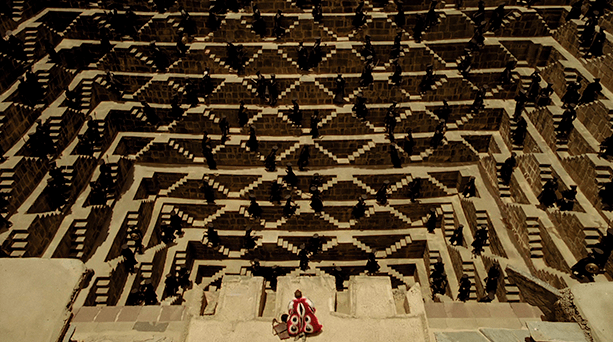

Feasting on the limitless possibilities of storytelling and imagination, director Tarsem Singh Dhabdwar might be accused of visual gluttony for his efforts in The Fall. Richly composed of frame after wondrous frame of seemingly impossible imagery, his production is an exercise of narrative simplicity and visual splendor. The story you’ve heard before, but you’ve never seen it quite like this—never with the inconceivable and tangible beauty painted with Tarsem’s detailed brushstrokes. From Eiko Ishioka’s baroque costumes to the stunning location shooting in upwards of twenty countries the world over, the film shows us sights the eye cannot believe are real, except they are: A centuries-old irrigation tank with labyrinthine staircases, a city painted blue, an elephant swimming in glimmering water, a face that emerges from the earth—they’re all shot from the expert eye of a devoted artist inspired by the limits of his medium, and how camera placement can underscore the world’s uncanniness and grandeur. Mostly eschewing the digital effects that today’s filmmakers rely on, The Fall presents a love letter to visual storytelling and, in its use of a stuntman as a protagonist, the tactile potential of cinema in the hands of dreamers and fabulists.

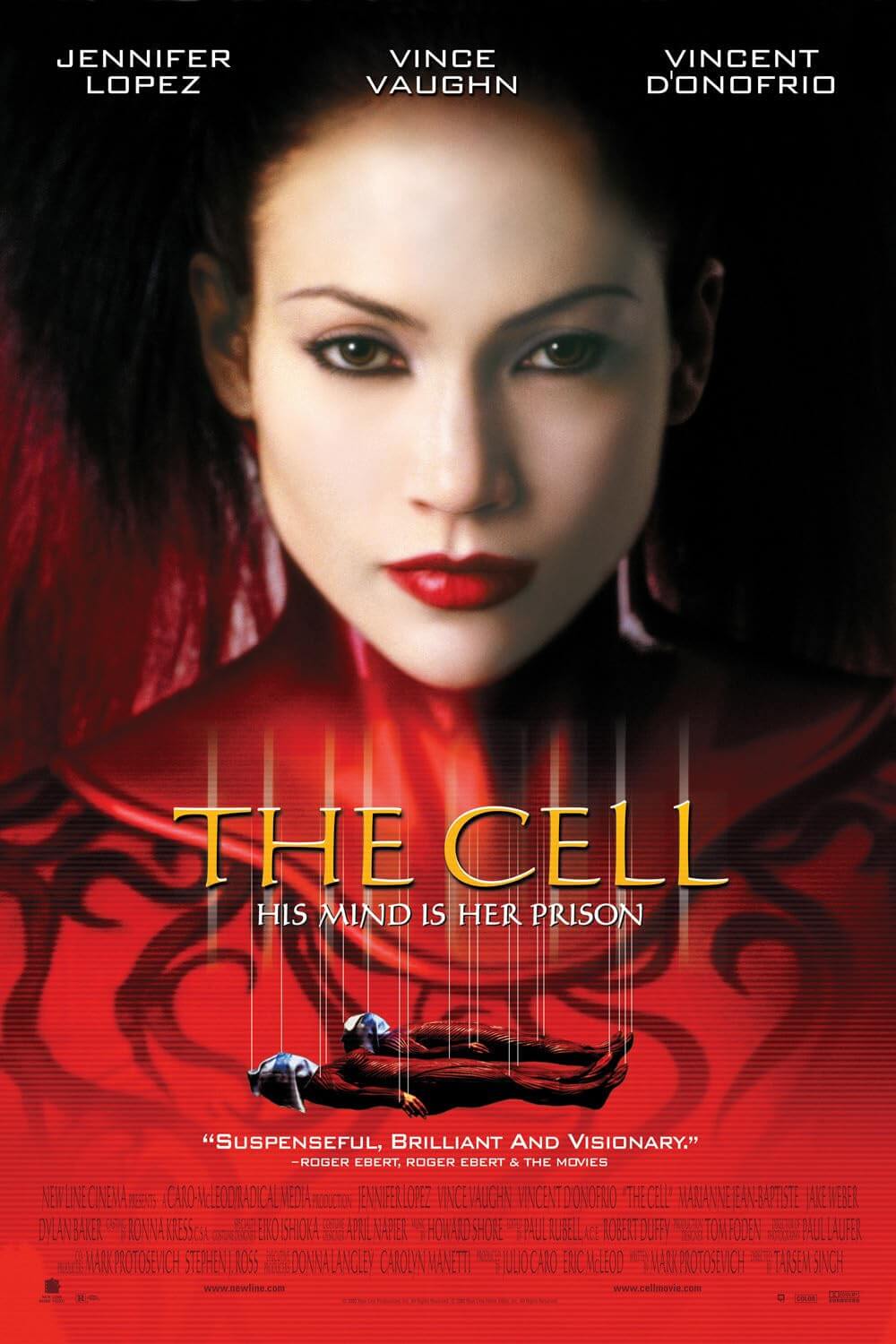

Known primarily for music videos and commercials, the Indian director went by Tarsem at the time of his film’s long-delayed wide release in 2008. Tarsem had dropped his last name when directing The Cell in 2000, a film so visually powerful that one forgets Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, and Vincent D’Onofrio starred. For The Fall, he also dropped his middle name, taking credit as simply Tarsem, an apt abbreviation for such a singular vision. The filmmaker borrows his screen story from Yo Ho Ho (1981), a Bulgarian film by director Zako Heskiya, about a young boy and an injured actor who dream up a pirate adventure while in the hospital. After purchasing the rights, Tarsem spent about 16 years creating a lookbook of exotic locations and visual concepts to bring the story to life. The production became a passion project while he made a name for himself, working with musicians such as R.E.M., Lou Reed, and En Vogue, and brands including Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Philips, and Nike. While shooting commercials in various locations around the globe, Tarsem had seen stunning buildings and natural wonders that he wanted to use in the picture. But no financiers would purchase his script, which he cowrote with Dan Gilroy and Nico Soultanakis.

The film started to become a reality when he ran the idea by directors David Fincher (Zodiac, 2007) and Spike Jonze (Adaptation., 2002), whom Tarsem met in music video circles and who receive “Presented by” credit here. The eventual production cost around $30 million, though Tarsem paid for much of the cost, funded by his commercial work. So The Fall carries the mark of being a labor of love and utter self-indulgence in the most inspired way. The filming took place over four years, with Tarsem capturing images from Bali, China, India, and various European countries, often while on assignment for his commercial projects. A Victorian hospital in South Africa played the primary location in Los Angeles. Other sites look impossible. At Deadvlei in Namibia, a painterly sequence unfolds on a white claypan accented by dead black trees and surrounded by burnt orange sand and a crisp blue sky. The viewer might even assume that digital artists conceived these images, such as the ancient stepwell of Chand Baori in India, which looks like a staircase from the mind of M.C. Escher. But Tarsem told The New York Times he wanted to avoid CGI in The Fall: “I had enough of that in my first film, as much as I enjoyed it. I decided in this one that the art direction was going to be in the landscape and in the costume design and nothing else.”

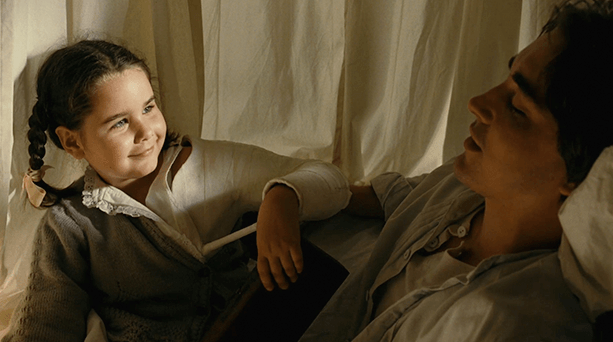

The film opens with glorious sepia-toned imagery shot in slow-motion, capturing a train on a bridge, a horse pulled from a river, and rescue crews scrambling to gather two men from the water—all set to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. Tarsem immediately evokes a sense of visual spectacle rooted in the real. However, The Fall alternates between reality and fantasy. Set in Los Angeles (“Once Upon a Time”) around 1915, the film begins in a hospital next to blooming orange groves. Young, impetuous immigrant girl Alexandria (Catinca Untaru), whose arm and shoulder are fixed in a cast—after “angry people” burned down her family’s home—discovers the oranges are perfect for throwing at the local priest. Ever curious, she finds her way into a ward where Hollywood stuntman Roy (Lee Pace) languishes in bed, paralyzed from the waist down after an on-set accident. Key to their bond, Alexandria’s father is dead, and Roy’s girlfriend left him after his misfortune. Both alone, the two quickly become friends. He tells her a story, spinning a yarn about how she was named after Alexander the Great. And Roy promises to tell her another storybook fable, but with a quid pro quo; he convinces young Alexandria to steal morphine pills in exchange for another chapter. But Roy’s plot is driven by its author and its listener’s wishes in a case of art imitating life.

The film opens with glorious sepia-toned imagery shot in slow-motion, capturing a train on a bridge, a horse pulled from a river, and rescue crews scrambling to gather two men from the water—all set to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. Tarsem immediately evokes a sense of visual spectacle rooted in the real. However, The Fall alternates between reality and fantasy. Set in Los Angeles (“Once Upon a Time”) around 1915, the film begins in a hospital next to blooming orange groves. Young, impetuous immigrant girl Alexandria (Catinca Untaru), whose arm and shoulder are fixed in a cast—after “angry people” burned down her family’s home—discovers the oranges are perfect for throwing at the local priest. Ever curious, she finds her way into a ward where Hollywood stuntman Roy (Lee Pace) languishes in bed, paralyzed from the waist down after an on-set accident. Key to their bond, Alexandria’s father is dead, and Roy’s girlfriend left him after his misfortune. Both alone, the two quickly become friends. He tells her a story, spinning a yarn about how she was named after Alexander the Great. And Roy promises to tell her another storybook fable, but with a quid pro quo; he convinces young Alexandria to steal morphine pills in exchange for another chapter. But Roy’s plot is driven by its author and its listener’s wishes in a case of art imitating life.

With Roy and Alexandria giving the story life, the film unfolds in an escapist tale of bandits rallying against Governor Odious (Daniel Caltagirone), a villain who has taken Sister Evelyn (Justine Waddell), the fantasy counterpart of Roy’s ex-girlfriend. Indeed, each character has a real-life equivalent. The hero, who begins as a stand-in for Alexandria’s father (Emil Hoștină), transitions into Roy as the Black Bandit—the leader of a posse, each member of which has a reason to want revenge on Odious: A one-legged actor (Robin Smith) at the hospital becomes a demolitions expert named Luigi; an orange harvester (Jeetu Verma) becomes an Indian warrior; the ice delivery man (Marcus Wesley) becomes a freed slave; a hospital orderly (Leo Bill) becomes Charles Darwin, who carries a sack with monkey assistant inside. In its technique of using real-world characters with correlating roles in the fantasy world, The Fall’s story structure is familiar—a tale that begins in the real world and folds its characters into a parallel fantasy. The Wizard of Oz (1939) remains perhaps the most venerable example of this, though Terry Gilliam’s dream trilogy (Time Bandits, 1981; Brazil, 1985; The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, 1988) would adopt a similar template. However, informed by Alexandria and Roy’s regular changes to the narrative trajectory of the fantasy, their story has less forward thrust than the scenes set in reality.

Much of the storytelling relies on the innocence and charm of then-six-year-old Romanian actress Catinca Untaru. Untaru’s earnest, unscripted reactions look and feel spontaneous, endearingly haphazard, and genuine. Tarsem admitted as much when he told The Guardian, “If you don’t fall in love with her then you’ll be so alienated that everything else just looks like a visual wank!” Fortunately, Untaru’s presence never feels like the work of a child actor, which can sometimes feel stagey and practiced. Rather, there’s a natural sense of play, particularly in her scenes with Pace, who had to improvise to keep up with her rambunctious behavior and broken English. The Fall would mark the fourth screen role for Pace, a Julliard-trained actor who made his debut playing trans woman Calpernia Addams in Showtime’s Soldier’s Girl (2013). He would later become famous for roles in various Hollywood franchises: the Twilight saga, the Hobbit trilogy, and the MCU. But his performance here, particularly in later scenes when the suicidal Roy’s story takes a downward turn, and Alexandria pleads with him for a happy ending, is heartbreaking. “Why are you making everybody die?” she cries. “It’s my story,” Roy defends through tears. “Mine, too,” she says.

Tarsem uses the story’s simplicity to consider the limitless visual possibilities of cinema, setting his film at the point in history where storytelling transferred from the oral tradition to the cinematic. But unlike other films about the power of movies, the theme remains largely implied in visual terms. Small flourishes with Alexandria, who has never seen a film, reveal that she has a rich visual life, playing with shadow puppets or looking at a photo and changing the perspective by alternating closed eyes. Cinema becomes tantamount to her imagination and exploration of vision. Elsewhere, Tarsem, working alongside cinematographer Colin Watkinson, creates what scholar Pauline Greenhill describes as a fluid “heterospatiality.” Although the film’s fantasy world takes place in a setting comprised of locations from all over the world, Tarsem assembles them as though they appear over the horizon from one another. This condensing of real places into a fictionalized environment is a miracle of cinema and editing. Tarsem’s commentary on cinema as fantasy becomes palpable near the finale, when Roy’s story takes a dark turn, and the visuals evoke the silent-era spectacles of Georges Méliès, with their many in-camera effects and hand-painted color frames. Finally, a montage of stunts from early Hollywood—daring car chases, high-rise leaps, death-defying train dodges—presents a loving ode to seeing the real thing in the movies.

Tarsem uses the story’s simplicity to consider the limitless visual possibilities of cinema, setting his film at the point in history where storytelling transferred from the oral tradition to the cinematic. But unlike other films about the power of movies, the theme remains largely implied in visual terms. Small flourishes with Alexandria, who has never seen a film, reveal that she has a rich visual life, playing with shadow puppets or looking at a photo and changing the perspective by alternating closed eyes. Cinema becomes tantamount to her imagination and exploration of vision. Elsewhere, Tarsem, working alongside cinematographer Colin Watkinson, creates what scholar Pauline Greenhill describes as a fluid “heterospatiality.” Although the film’s fantasy world takes place in a setting comprised of locations from all over the world, Tarsem assembles them as though they appear over the horizon from one another. This condensing of real places into a fictionalized environment is a miracle of cinema and editing. Tarsem’s commentary on cinema as fantasy becomes palpable near the finale, when Roy’s story takes a dark turn, and the visuals evoke the silent-era spectacles of Georges Méliès, with their many in-camera effects and hand-painted color frames. Finally, a montage of stunts from early Hollywood—daring car chases, high-rise leaps, death-defying train dodges—presents a loving ode to seeing the real thing in the movies.

Sadly, Tarsem’s filmic trompe l’oeil was all but discarded at the box office, opening in limited release against several summer blockbusters about two years after its 2006 debut at the Toronto Film Festival. It became a rare gem found by curious cinephiles, and it remains less popular and decidedly less mainstream than Tarsem’s subsequent work on his mythical fantasy Immortals (2011); misguided Snow White adaptation, Mirror Mirror (2012); and sci-fi actioner Self/less (2015). Roger Ebert hailed it as a “visual orgy.” Other critics decried it for the same reasons, complaining that Tarsem was more interested in visuals than complex characters or a compelling narrative. Much of the publicity at the time noted the film’s supposed absence of CGI. “Singh claims there is no CGI in his breathtakingly visual film,” wrote Damon Wise in The Guardian. And yet, watching the film fifteen years later, it’s evident that Tarsem used the “no CGI” angle as a marketing ploy. A scene where an object moves underneath a character’s flesh is a clear work of computers, and so is a shot involving Wesley falling on several arrows that have penetrated his character’s back. Several other minor examples appear throughout the film, but no matter; the result speaks for itself in a thousand stunning pictures, enchanting the viewer beyond measure. The most apparent deviation comes in the form of animators Christoph Lauenstein and Wolfgang Lauenstein’s nightmarish stop-motion dream sequence, which today looks straight out of Mad God (2022).

The Fall belongs on a shortlist of ambitious and excessive films that challenge any pejorative associations with the word indulgent. Rarely does every shot of a film evoke such mouth-agape awe and a sense of wonderment flowing through every moment. Of course, as Tarsem suggested, the film might seem empty if not for its charming leads and their apparent chemistry. But even without the endearing story at the center, the eye-popping scenery and costumes would be enough to remind the audience about the power of visual storytelling. Fortunately, as Untaru and Pace tug our heartstrings and reduce us to tears, the predominantly natural visuals mesmerize us. Tarsem achieves something that belongs in the same category as works by Gilliam, Ken Russell (The Devils, 1971), and the Wachowskis (Cloud Atlas, 2012)—filmmakers inspired to cram so many details into the frame that some audiences respond with sensory overload. And while his later work would never match the visionary heights reached in The Fall, the film remains evidence of Tarsem’s talent and a lovingly made testament to the link between cinema and imagination.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on April 12, 2023. Thank you for your continued support and patronage, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

Greenhill, Pauline. “Camera Obscura and Zoetrope: Tarsem and Magic/Reality in Transcultural Fairy-Tale Film.” Narrative Culture, Vol. 6, No. 2, Thinking with Stories in Times of Conflict (Fall 2019), pp. 119-139.

Kehr, David. “Special Effects From the Real World.” The New York Times. 11 May 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/11/movies/11kehr.html. Accessed 8 April 2023.

Wise, Damon. “Final Fantasy.” The Guardian. 4 October 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2008/oct/04/fall.tarsem.singh. Accessed 8 April 2023.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review