The Wedding Banquet

By Brian Eggert |

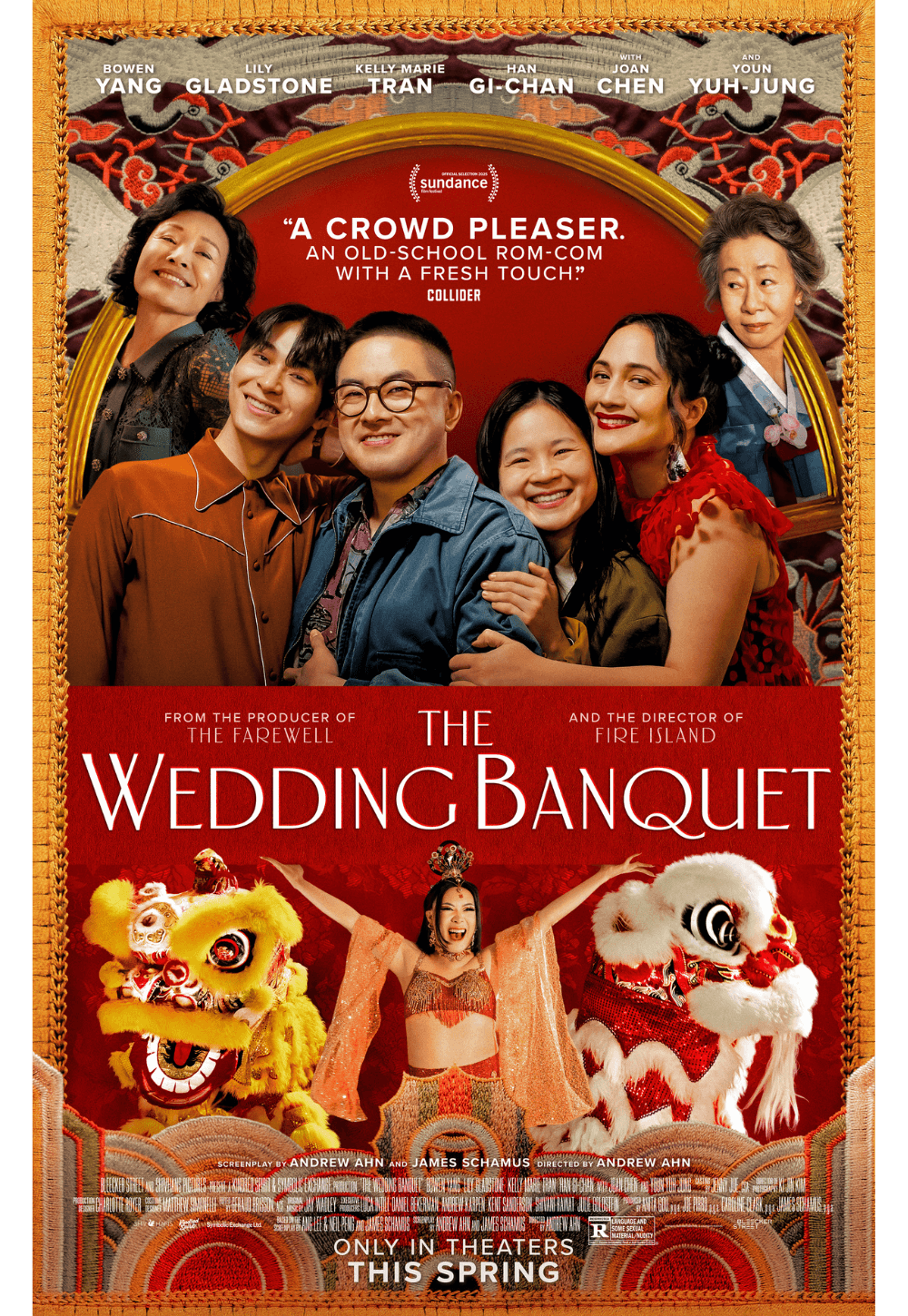

The Wedding Banquet embarks on a thankless task: remaking perhaps not an all-time classic, but a perfectly entertaining movie that required little modernization to feel relevant. Ang Lee’s 1993 original of the same name was the Taiwanese filmmaker’s second feature after Pushing Hands (1991). The 1993 version involved a relatively unconventional premise at a time when there was little LGBTQ+ representation in the cinema, following a queer man in America who agrees to marry a Chinese woman to secure her green card for helping him appease his parents’ expectations for a traditional marriage. The wacky rom-com antics register as overwhelmingly 1990s by today’s standards, but the emotions still land. The remake, directed by Andrew Ahn, premiered at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival to an enthusiastic response. Although it adds new wrinkles to the original’s setup, it feels less novel, given the last thirty years of similar material in cinemas and on television.

Ahn’s version, which he co-wrote with James Schamus, Lee’s longtime producer and co-writer of the original, looks and feels like a direct-to-streaming affair. Ahn and cinematographer Ki Jin Kim deliver scenes that look like they were shot for a small-screen debut, with many close-ups and bright, overlit imagery designed to look good on a smartphone. Doubtless, this is an intentional strategy among some filmmakers who plan to take their projects to the festival circuit, where many studios and streamers shop for new acquisitions. After all, Ahn’s last feature, Fire Island (2022), had a similar aesthetic and debuted exclusively on Hulu. But The Wedding Banquet makes a theatrical bow, thanks to Bleecker Street, and it’s the sort of crowd-pleasing movie that will work best in a theatrical setting.

The story follows two couples living in a Seattle home. A lesbian couple, Lee (Lily Gladstone) and Angela (Kelly Marie Tran), lives in the house proper, and they have been trying to have a child. Lee wants a baby, but after her second failed IVF, she cannot afford another attempt and wonders if she’ll ever get pregnant. Lee tries to convince Angela to try IVF, but Angela doesn’t want the whole giving birth experience—her issues with her mother, May (Joan Chen), cause her to worry that she’ll become a lousy parent. Living in their converted garage is Chris (Bowen Yang), a gay man reluctant to marry his wealthy partner, Min (Han Gi-chan), a trust fund kid from a wealthy South Korean family who needs to secure his green card. Min hatches a scheme: Min will marry Angela to get a green card, and in exchange, he will pay for another IVF treatment for Lee.

Ahn and Schamus pile on one complication after another. Upon hearing about Min’s engagement, his grandmother, Ja-Young (Youn Yuh-jung), insists on coming to America for the ceremony. Wait, the ceremony? Yes, Ja-Young insists. What might’ve been Min and Angela making a quick trip to the courthouse becomes a traditional wedding with photos, costumes, and the whole shebang. Of course, all of this deception and absurdity would be solved if everyone just talked to one another like adults and spoke the truth, but if they did that, there wouldn’t be a movie. Matters are further complicated when, after a drunken night of complaining about their partners and predicament, Angela and Chris have sex, and she becomes pregnant. If Lee’s original seemed to flirt with disaster as only a rom-com can, the remake’s over-the-top revision of the story is a bit much.

The plot’s outrageousness only accentuates what doesn’t work about the movie because the two main couples have little romantic chemistry. I never believed that Lee and Angela were a longtime pair, save for a single scene featuring them on a couch, having a snack in their cozy clothes. Also, Chris and Min lack the immediacy that might’ve made this situation more dire, funny, and emotionally involving. If none of the lovers’ relationships shine, the platonic friendships and family dynamics at least have weight. Every scene with Chen and Youn (who won an Oscar for her performance in Minari, 2020) has the intended effect, as these experienced performers play their scenes with emotional intelligence, without mugging for the camera, as Yang and Han sometimes do. Tran fares better, showing some considerable range, while Gladstone’s low-energy presence is earnest and wounded but less successful in capturing the heightened tone of this material.

I probably did The Wedding Banquet a disservice by watching it at home, alone, on a digital screener. I noticed little spark to the material, despite Ahn’s best efforts to deliver broad rom-com antics with a dramatic undertone. I regret not seeing the movie with a crowd whose laughter and other vocalized emotions might have proved contagious. Still, I prefer the original version. Ahn boosts every moment for full comedic effect, whereas Lee showed some restraint. And while the 1993 version was already a series of zany rom-com circumstances, this one overemphasizes the conflict with one too many swaps, coincidences, and misunderstandings to register as genuinely affecting.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review