In the Lost Lands

By Brian Eggert |

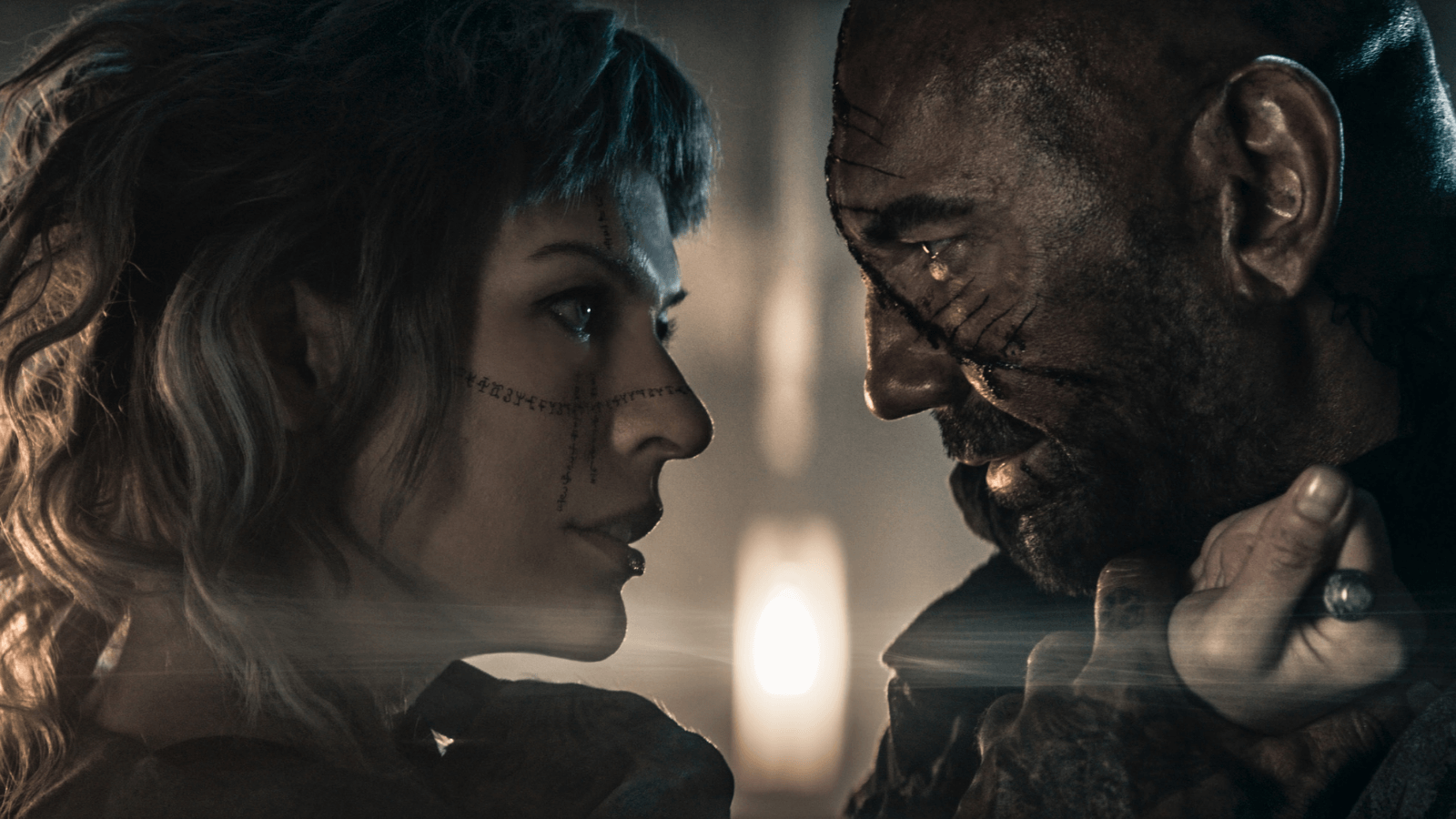

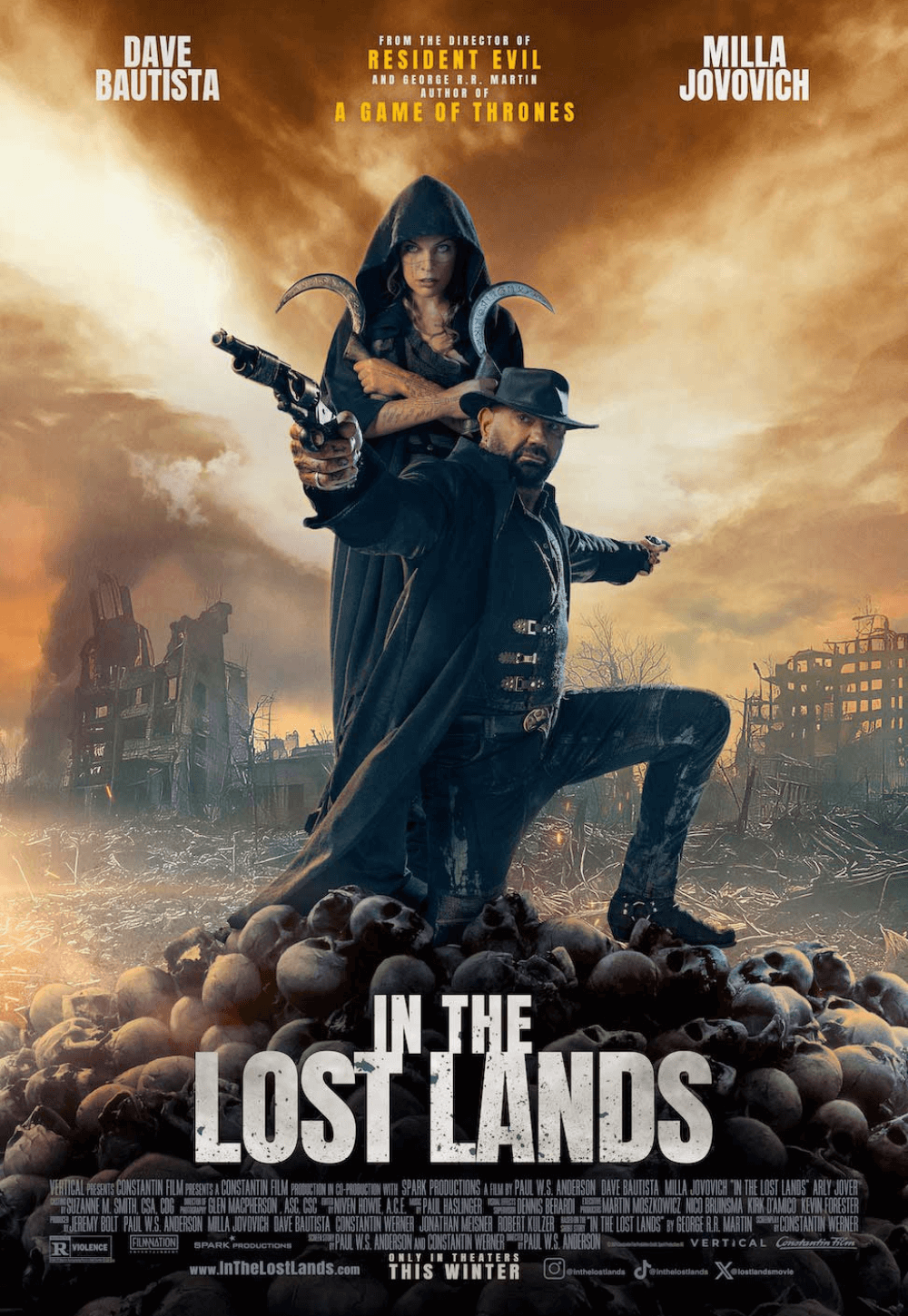

“If you’ve got the time and the stomach for it, I’ve got a story for you,” says Dave Bautista’s post-apocalyptic drifter Boyce, looking down the camera’s lens. This moment opens In the Lost Lands, director Paul W.S. Anderson’s new movie, based on George R.R. Martin’s 1982 short story, and it immediately signals the rough road ahead. Boyce ambles into an annihilated city ruled by a dying medieval Overlord (Jacek Dzisiewicz). While there, he teams with a sorceress named Gray Alys (Milla Jovovich) to help the young Queen (Amara Okereke) seize power. “This is the story of how we met,” he explains, “and how she saved the both of us.” The prologue makes even less sense by the end, raising questions about who he’s talking to (hint: it’s not us) and his awkward approach to telling their story. The whole convoluted adventure involves werewolves, zealots, demons, and talk of treasure and magic. It plays like a bad imitation of better post-apocalyptic movies and video games. The experience is lifeless, joyless, derivative, and staggering in its ineptitude.

Adapted by screenwriter Constantin Werner, with Anderson contributing to the screen story, In the Lost Lands sets up Bautista as a mysterious gunslinger who looks like a pro-wrestler and has an origami unicorn tattooed on his neck (Bautista’s actual Blade Runner tattoo). Jovovich, playing another kick-ass hero alongside her eight previous collaborations with husband-director Anderson, is a witch with the ability to control people’s minds, grant wishes, and appear with ever-fresh makeup (almost like she’s a L’Oréal brand ambassador). Together, they head out into the wasteland, seeking a mysterious werewolf before the next full moon, which will give the Queen shape-shifting powers. They speak in hushed, serious tones, utterly humorless; both look stiff and uncomfortable, like their only direction from Anderson was to “act like a badass.” All the while, they’re hunted by Ash (Arly Jover), a Christian fanatic. And back in the kingdom, the Queen and a religious leader (Fraser James) scheme for power in, dare I say, a game of thrones.

All of this might be interesting—it reminded me of the Fallout game series—if the screenplay had anything to offer besides tired ideas and clichés, but it doesn’t. Every story component and many visual compositions feel Frankensteined together from better movies. At one point, Boyce is shot, and Gray Alys helps him extract the bullet. “If you don’t mind,” he says, “I think I’ll pass out now.” It’s a deadpan comic relief moment lifted almost verbatim from a Robert De Niro line in Ronin (1998). There’s a lot of that going on here, from world maps in a Game of Thrones color scheme to a frontier station that looks almost identical to the opening of Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). The list could go on. It’s one thing to let great movies and shows inspire you or pay homage to them in your work; it’s another to unabashedly copy them because you have no original or innovative ideas.

The movie has all the usual problems of any Anderson production: an overreliance on digital effects, incohesive editing, no shot-to-shot progression, a desperate yearning to be cool, and clunky writing. Seldom do the characters appear to be standing on actual sets; the entire production looks like it was captured against greenscreens and filled in with VFX software. The movie’s CGI aesthetic alternates between color saturations—amber in some scenes, a metallic hue in others—and it’s accented by a distracting amount of artificial lens flares and digitized backgrounds, earning comparisons to Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004), Van Helsing (2004), and Priest (2011). As ever, Anderson’s action scenes feel informed by video game dynamics, such as a POV werewolf-cam that plays more like a first-person shooter. And since Anderson has made his career adapting video games to movies—from Mortal Kombat (1995) to Resident Evil (2002) to Monster Hunter (2020)—his choices track. Through it all, Paul Haslinger’s lofty music plays as though accompanying a grand epic, which is a miscalculation that only underscores how not epic the movie feels.

In the Lost Lands belongs on a list next to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), The Chronicles of Riddick (2004), and other messy mid-2000s genre filmmaking. Anderson seems locked in that mode of filmmaking; he’s unwaveringly committed to subpar CGI, over-edited action sequences, and oppressive moodiness that drains the material of any fun. He hasn’t learned from his mistakes, shown a willingness to change his aesthetic, or grown as a filmmaker, leaving his films staggeringly and frustratingly consistent. Part of that is because his low-budget movies usually make money despite widespread critical panning. With Anderson taking a five-year break since his last feature, Monster Hunter, and tackling literary source material, I hoped he might have reinvented himself with In the Lost Lands. But no, he’s up to his same old tricks, and that’s disappointing.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review