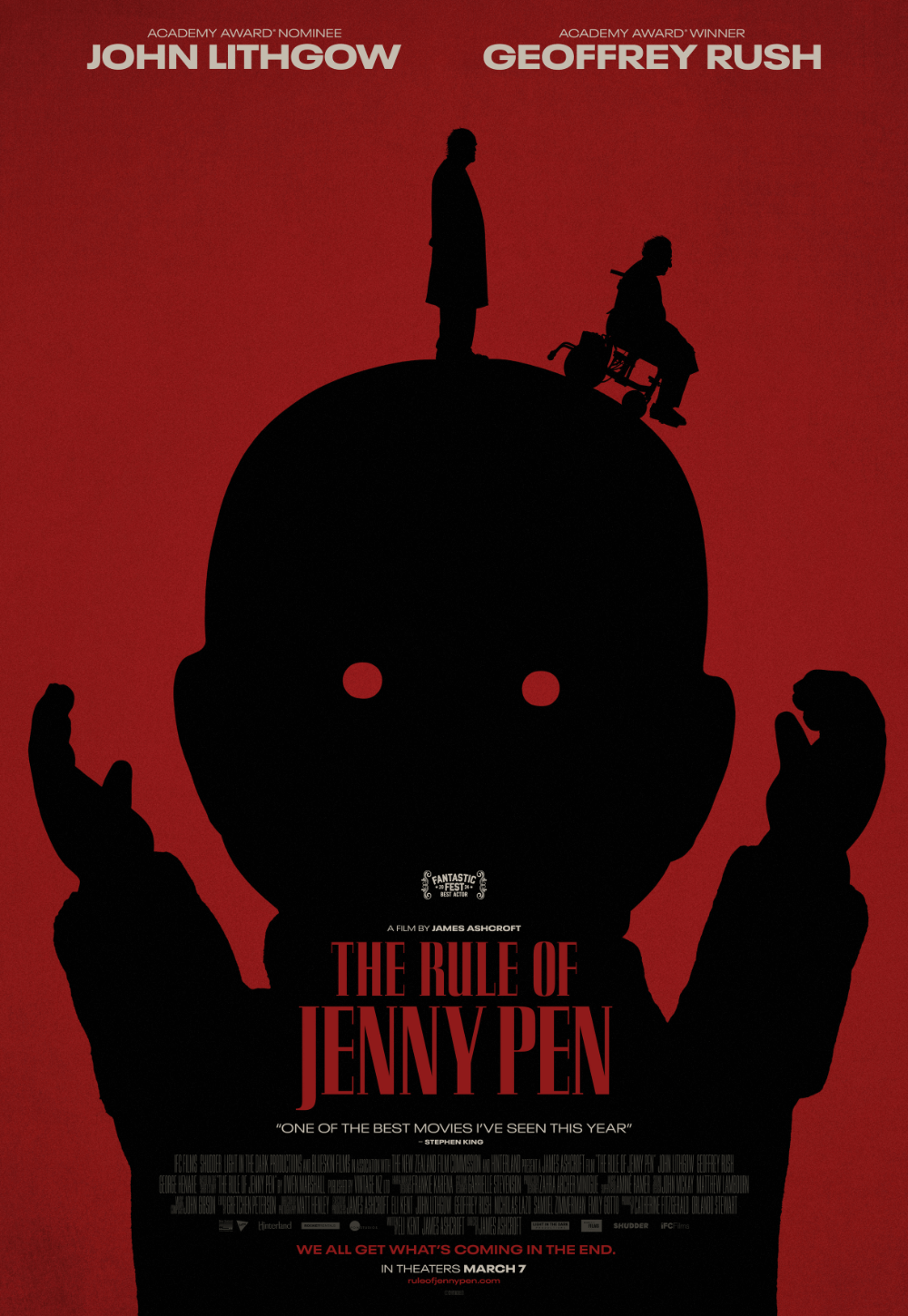

The Rule of Jenny Pen

By Brian Eggert |

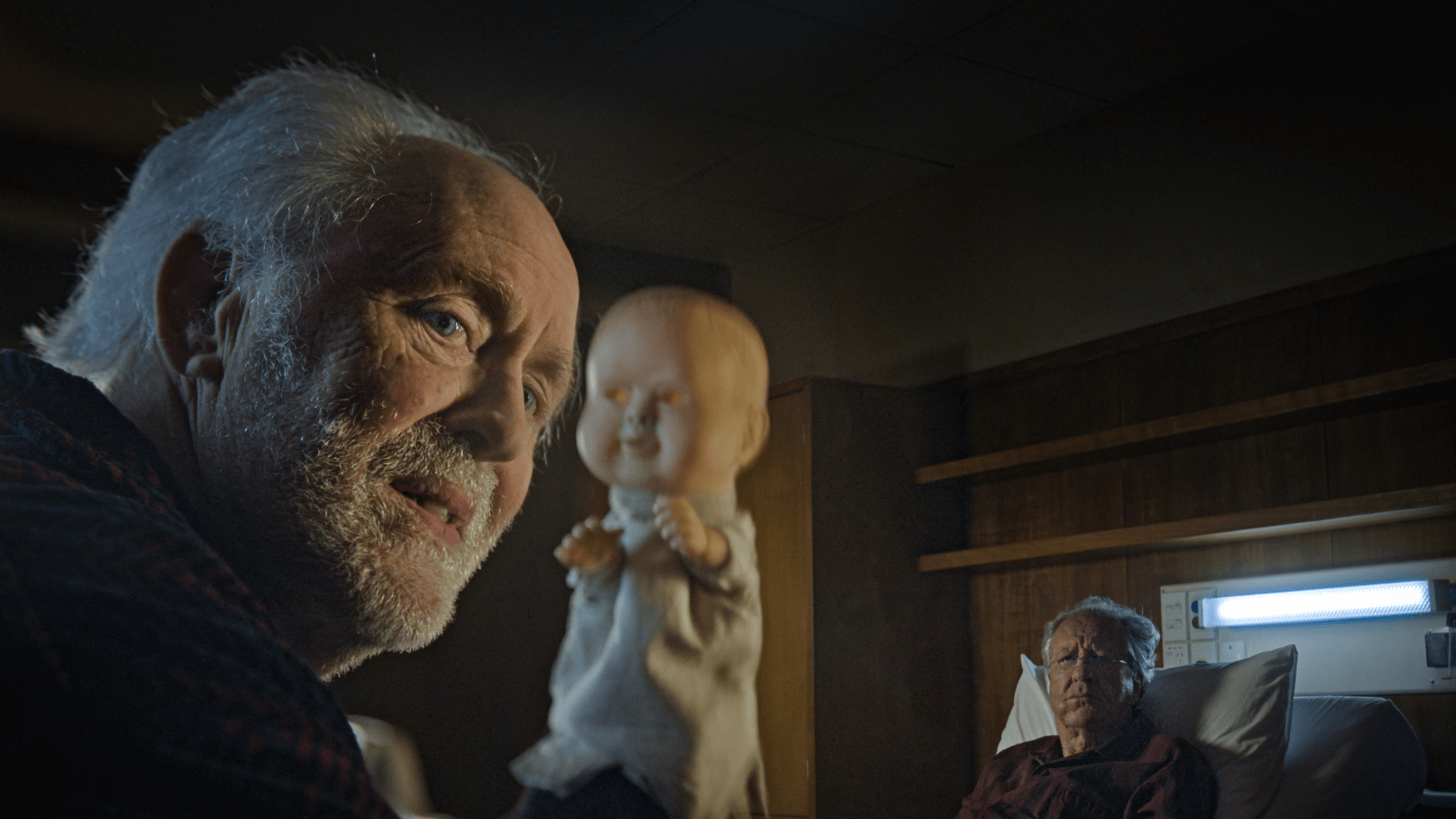

In the first sequence of The Rule of Jenny Pen, a New Zealand chiller based on Owen Marshall’s short story, Judge Stefan Mortensen (Geoffrey Rush) presides over a pedophile case. His entire life, the judge has been in control, carrying himself with an authority and composure that earned his appointment on the bench. But as he casts down a scathing verdict, he begins losing the feeling in his right arm, he stumbles over words, and his vision blurs. Before long, Mortensen’s stroke takes him from the courts to a senior care facility, where he shares a room with a Maori resident, Tony (George Henare). Vowing to improve his motor function and get out of there, the curmudgeonly, well-educated Mortensen must contend with a morbid reality: he and the other disempowered residents are at the mercy of David Crealy (John Lithgow), a crazed patient who wears a hollow-headed plastic doll on his hand like a Mr. Rogers puppet, which he calls Jenny Pen, and creeps around the facility, tormenting others who are helpless to fight back.

Few films confront the reality of getting old—our powerlessness over time and the frailty of the mind and body. Although there’s no shortage of senior citizens in the movies, they often occupy lazy tropes: from the kooky antics in the Grumpy Old Men series to the quirkily cute bunch in The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011), from the cranky codger in Gran Torino (2008) to Alexander Payne’s unsentimental portraits of the elderly in About Schmidt (2002) and Nebraska (2013), from a loving grandfather in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) to the downright detestable grandma in The Front Room (2024). The realities of getting old—physical ailments, neglect, solitude, abuse, and mental decline—are seldom the subject of a movie. Many of us spend so much of our lives trying to preserve our youth that old age becomes something unfaceable in our movie-watching habits.

Director James Ashcroft and his co-writer Eli Kent fashion a nightmarish eldercare scenario where our hero is a cranky, enfeebled authority figure, who still manages to stand up for himself. The adjustment from personal autonomy to internment in a care facility, with its half-interested employees and Kafkaesque rules, would be maddening enough without Crealy. Here’s a character who moves freely through the facility at night with stolen key cards, lurking behind drawn red curtains and casting a monstrous shadow over his victims. His doll might be absurdly comical if not for its pure malevolence. Note the way light penetrates the doll’s head, making it look as though its empty eye sockets are glowing. That image haunts the seniors, who remain silent out of fear. Worse, Mortensen must watch helplessly as Crealy terrorizes Tony, tearing up his family photos, telling racist jokes, and yanking at his catheter. Then Crealy asks, in his usual, demented routine, “Who rules?” Tony mutters the expected reply: “Jenny Pen.” Then Crealy pulls up Jenny Pen’s dress and orders, “Lick her asshole”—forcing Tony to lick the back of his hand. It’s jaw-droppingly twisted.

The Rule of Jenny Pen is a superbly acted film, propelled by its two leads, who also serve as executive producers. Lithgow is an unparalleled actor, capable of playing some of cinema’s most affable characters, such as a transgender woman in The World According to Garp (1982) and a lovable alien on 3rd Rock from the Sun (1996-2001). But he has also transformed into vile monsters in Brian De Palma’s work (see 1981’s Blow Out and 1992’s Raising Cain) and the Showtime series Dexter. Behind piercing blue eyes—color contacts, like a doll’s eyes—and crooked yellow teeth, he inhabits a long-tenured staff member turned patient who exploits his knowledge to rule in secret. Although given a slight backstory, Crealy’s lunatic behavior speaks for itself. He takes pleasure in stealing soup, kicking shins, pouring urine on laps, and blaming others for his crimes. Lithgow is matched by Rush, a renowned stage actor who never overplays the judge’s memory loss and physical decline, presenting the character as resilient if impaired. Henare is also terrific as a proud Maori who’s reduced to quaking in fear from Crealy’s nocturnal visits.

Adapting another Marshall short story after his 2021 feature debut, Coming Home in the Dark, Ashcroft seems to set The Rule of Jenny Pen before the days of security cameras and smart devices, both of which could capture evidence of Crealy’s schemes. However, the brief presence of Tony’s laptop suggests the film takes place in the Digital Age, prompting one to wonder why someone hasn’t caught Crealy’s demented antics on video. The soundtrack, too, hints at an older time with obscure but pointed songs: Reminding them all that they’re not long for this world, “If I Only Had Time” by John Rowles plays against Crealy dancing amid other residents, stepping on their toes and shoving them until they abandon the dance floor, leaving him alone. Ashcroft imbues the daytime sequences with the banal horrors of full urine bags, assisted baths, and lousy-looking food, whereas nighttime brings surreal, giant-sized nightmares of Jenny Pen and Crealy, amplified by Mortensen’s rapid descent into dementia.

While The Rule of Jenny Pen grapples with the grim aspects of elderly abuse, mental decline, and the depressing reality of senior living facilities, it’s also a stirring yarn about standing up to bullies. Crealy’s reign of terror has only gone on so long because others refuse to speak up. His tyrannical behavior targets the weak and defenseless, but he also urgently silences dissenters like Mortensen. Ashcroft tells a story about the challenge of standing up to persecutors who use intimidation and punishment to influence others. Most of us must contend with bullies: they terrorize the playground and hold political positions. Commanding a terrific cast with two unforgettable lead performances from Lithgow and Rush, Ashcroft reminds us that most bullies cower when someone stands up to them with enough force. The Rule of Jenny Pen is evergreen in its message, whether set in the specific locale of a senior home or applied to any number of metaphoric situations.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review