Parthenope

By Brian Eggert |

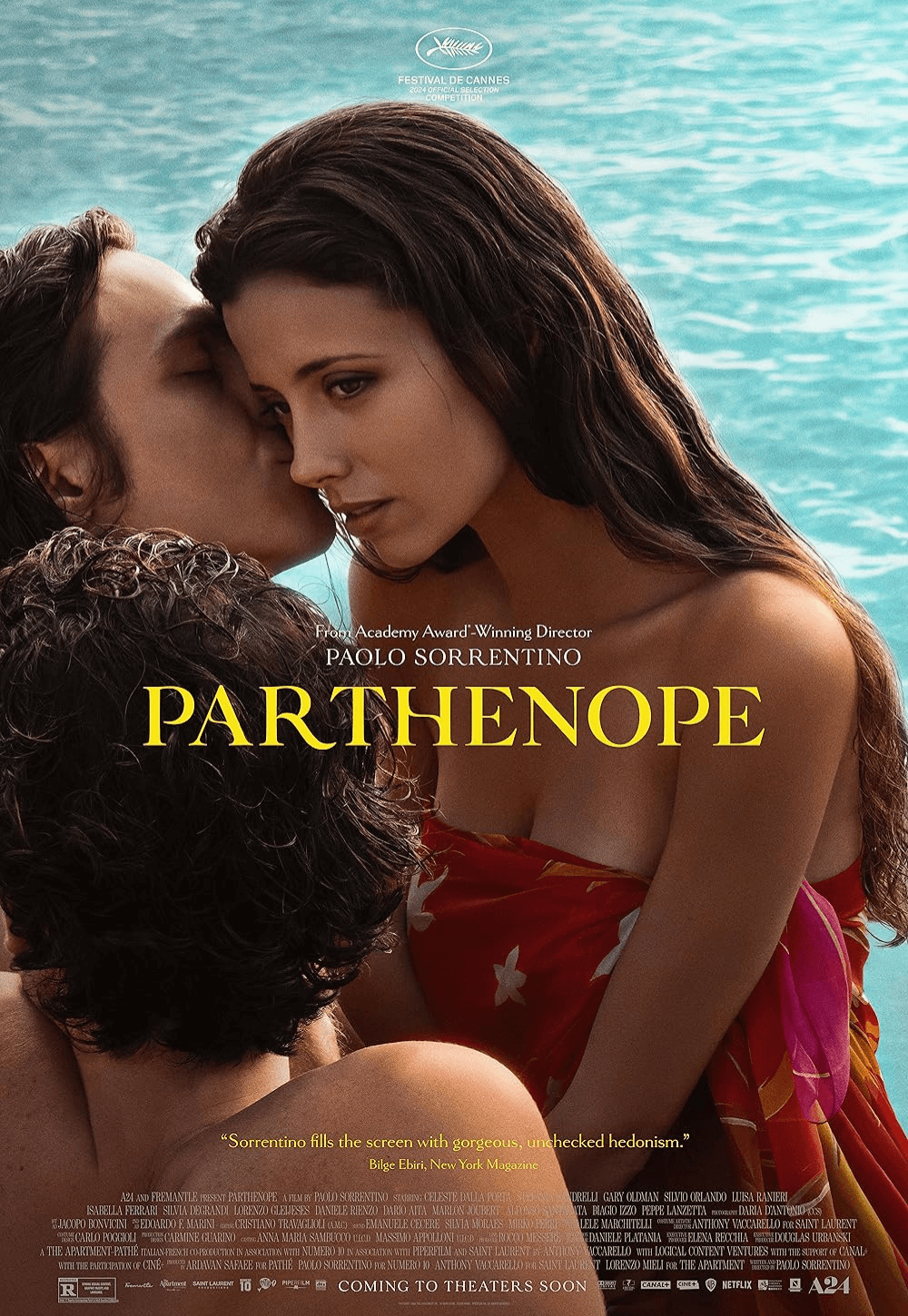

Paolo Sorrentino’s Parthenope stars Celeste Dalla Porta as a woman whose beauty is uncannily transfixing. Yet, she remains unsure of how to wield the desire she evokes and undecided about what to do with her future. Set in Sorrentino’s hometown of Naples, the film looks at the eponymous character’s youth and search for meaning. However, the writer-director gets lost along the way, often dwelling on episodes where her presence prompts others to obsess over her appearance. Everyone from a wealthy magnate with a helicopter to a local bishop becomes infatuated with her. What seems at first like a coming-of-age story becomes more episodic and complex as the A24 release spans decades but offers little more than cryptic insights about its protagonist. A patchwork that could benefit from some restructuring and fleshing out of its ideas, Sorrentino’s latest acknowledges that people only begin to gain perspective on their lives after the rush of discovery, youth, and desire fade, giving way to deeper reflection.

The film shares its name with one of the sirens who sought to lure Odysseus away from his journey in Homer’s epic poem. Anticipating this, Odysseus plugged his ears with wax and tied himself to his ship’s mast, ensuring he could escape her song. Unable to ensnare Odysseus, Parthenope cast herself into the sea in despair. Her body washed ashore, and the ancient Greeks named the colony Parthenope in her honor, only for the Greeks to rename the spot Naples centuries later. The myth imbues Sorrentino’s character with a mystical allure, her beauty forever entwined with longing and sorrow. Sorrentino imagines a modern-day counterpart in Porta, the 27-year-old lead who plays the arresting but aimless cipher-of-a-character at the film’s center. Sorrentino opens his story in 1950 with her portentous water birth, where her shipping magnate godfather (Peppe Lanzetta) names her after the mythic island—as if sealing her fate.

Will Parthenope fulfill the legacy her name implies, or will she transcend that definition? Her family and others tell her to become a diva, knowing she can get by on her looks. In a curiously underdeveloped episode, she meets the writer John Cheever (Gary Oldman), who asks, “Are you aware of the disruption your beauty causes?” And Parthenope considers resigning herself to beauty—she even flirts with the notion of becoming an actress before changing her mind after meeting the eroded diva Greta Cool (Luisa Ranieri). Even as the film wrestles with the notion of Parthenope’s future, she learns to control her presence and enjoy the pleasures of attraction, much to the chagrin of family friend Sandrino (Dario Aita) and her brother Raimundo (Daniele Rienzo), both of whom remain infatuated. In a scene that recalls the three-way dance in Y tu mamá también (2001), she stands between them, discouraging neither. Loaded exchanges between the siblings, followed by Raimundo’s demise, suggest there was more between them than just desirous looks.

Sorrentino’s portrait somehow feels less constructive than, say, Luca Guadagnino’s many-layered I Am Love (2010) and A Bigger Splash (2015), two Italy-set dramas featuring no end of gazing and sensuality, with similar incestuous implications in the latter film. Fortunately, Sorrentino has more on his mind than just appreciating beauty. Parthenope studies anthropology at the university level and can quote French philosophers. In an early scene, she confronts an academic panel headed by her initially unconvinced professor (Silvio Orlando), demonstrating her aptitude for complex theories—a persistent reminder that others seldom see beyond her appearance. Still, after she spends endless hours in the mirror, caught by Sorrentino’s lingering camera, she gradually realizes that her beauty is a tool. As Cheever tells her, “Beauty is like war. It opens doors.”

Sorrentino’s camera is constantly ogling Parthenope, much like the film’s other characters do, in awe of her appearance. He delights in presenting Porta to the viewer, hoping to tantalize his audience. But he also shows Parthenope enjoying her reflection with the same pleasure others have while leering at her. It’s all a bit monotonous. Produced in part by the luxury fashion house Saint Laurent, the production is luscious and extravagant, boasting no shortage of gorgeous imagery, stylish costumes, and nostalgia for the Naples of Sorrentino’s memories. His screenplay, however, offers no great insights that haven’t been expressed better in his earlier work, from The Great Beauty (2013) to Youth (2015). Like his other films, Parthenope is the product of a visualist whose individual scenes function well as momentary clips or pieces of a trailer, showcasing the clever lines of dialogue and scenes in the Mediterranean’s impossibly stunning light—all set to Lele Marchitelli’s score, featuring a mischievous clarinet and grandiose orchestra.

Every moment of the film is an exquisite act of seduction, even, strangely, Sorrentino’s grotesque asides and surreal flourishes. When Parthenope’s godfather, a great toad behind sunglasses, asks his goddaughter whether she would marry him if he were 40 years younger, she asks whether he would marry her if she were 40 years older. He laughs and calls her a “sly one.” There’s a charm to how she handles the uncomfortable implication of his question. Why she acquiesces to another toad, this one a Catholic bishop, again behind sunglasses, remains a mystery to me. Clearly, Sorrentino draws from Federico Fellini’s fabulist introspection and even dabbles with downright surrealism: note the enormous shut-in baby thing or the monstrous, insect-like street cleaner that blocks a funeral procession. Another out-there sequence finds Parthenope participating in an underground spectacle with an audience of mostly older men who have paid to watch a young couple make love on full display. The way she looks at the woman participant with ache and sympathy is devastating.

All of these episodes might have received some perspective in the film’s coda, with Parthenope in 2023, played by Stefania Sandrelli, looking back on her life and still unresolved about her choices. “I was sad and frivolous, determined and listless,” she reflects. “Alive and alone.” However, the film doesn’t allow this older, wiser version of the character to imbue the earlier scenes with profound meaning, leaving them to feel like a random collection of memories. That is, of course, what they are. But Sorrentino doesn’t lend them perspective; he seems to equate the frivolities of youth with cinematic voyeurism, noting how scopophilia seldom sees beyond the surface. Even while Parthenope critiques the limitations of the male gaze and desire, which have been so omnipresent in the last century-plus of cinema and whole history of art, recognizing that women rarely get the dimension they deserve, it cannot resist falling into its own snare. Unfortunately, Sorrentino’s affinity for surfaces means he sabotages his film’s ideas by inadequately conveying Parthenope’s inner life.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review