Armand

By Brian Eggert |

Norwegian writer-director Halfdan Ullmann Tøndel explores tense material with his debut film, Armand, but he occasionally makes obscure choices that don’t always articulate the material’s psychological layers. Renate Reinsve, who broke out after 2021’s The Worst Person in the World, stars as Elisabeth, an actress called to her (unseen) son Armand’s school to discuss an incident. A classmate named Jon has accused her six-year-old boy of what a young teacher, Sunna (Thea Lambrechts Vaulen), calls “a case of sexual deviation.” Jon’s parents, Sarah (Ellen Dorrit Petersen) and Anders (Endre Hellestveit), and members of the school’s staff discuss what happened. Their assessment goes from “nothing serious” to a situation that may require the authorities, namely child protective services. Gradually, what begins as a straightforward, claustrophobic drama unravels into a borderline avant-garde piece. While fascinating and filled with superb performances and confident filmmaking, Armand doesn’t always add up to a clear artistic outcome.

Much has been made of this first-time director’s grandparents, Ingmar Bergman and Liv Ullmann, inciting plenty of comparisons between Armand and Bergman’s work. To be sure, certain aspects resemble Persona (1966), which starred Ullmann as an actress who works through a mind-bending identity crisis. However, Ullmann Tøndel’s directing style reminded me less of Bergman’s and more of his Nordic contemporaries, such as Joachim Trier (Oslo, August 31st, 2011) and Thomas Vinterberg. The latter director made The Hunt in 2012, telling a similar story of unconfirmed accusations and the social fallout. However, the material also brought to mind The Teachers’ Lounge (2023) in its scenes of school staffers debating what’s right and how the school should respond. Like that film, the school in Armand becomes another character. Besides claustrophobic hallways and classrooms, the story takes place on a hot day when the school’s malfunctioning fire alarm system blares intermittently.

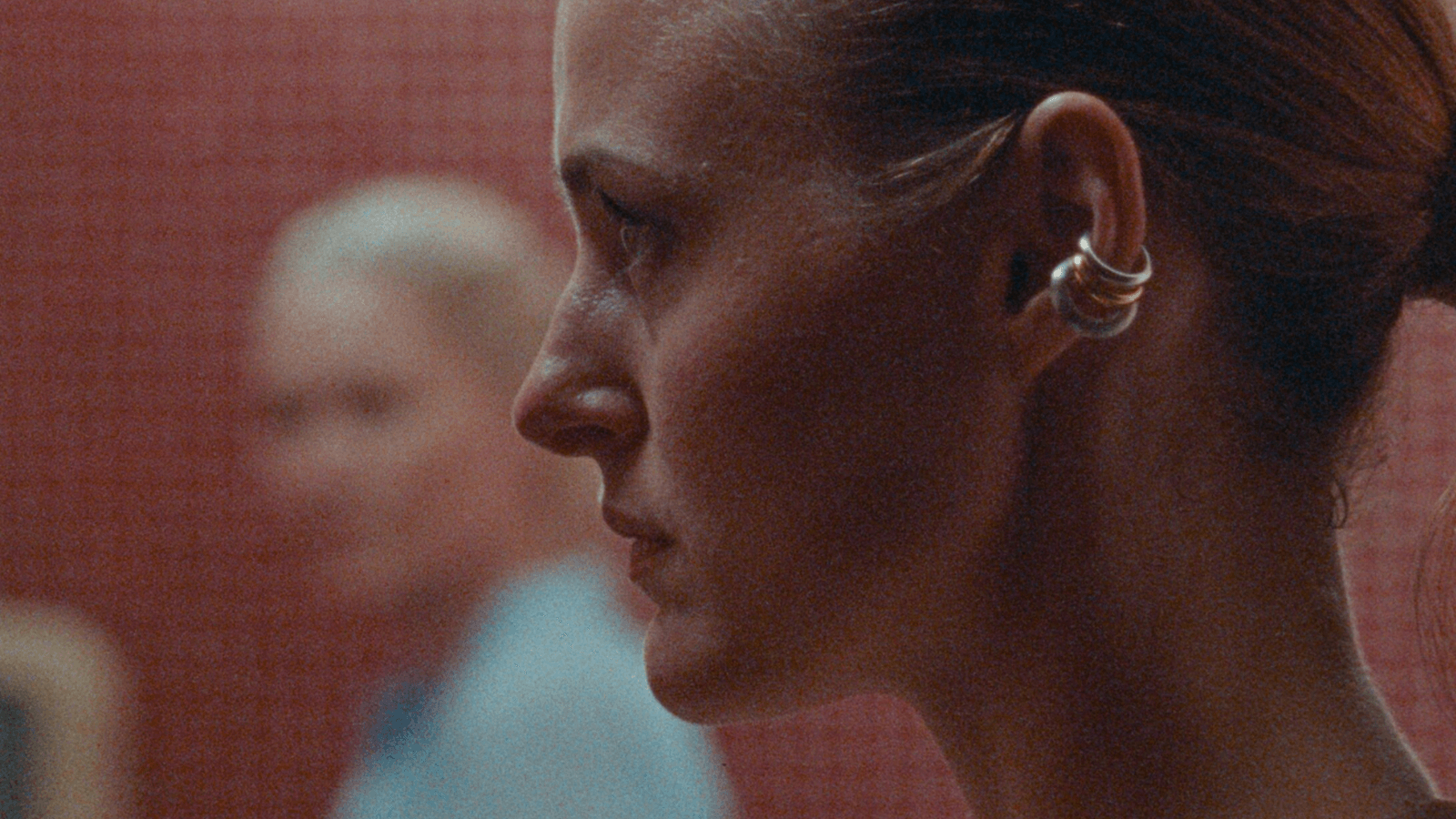

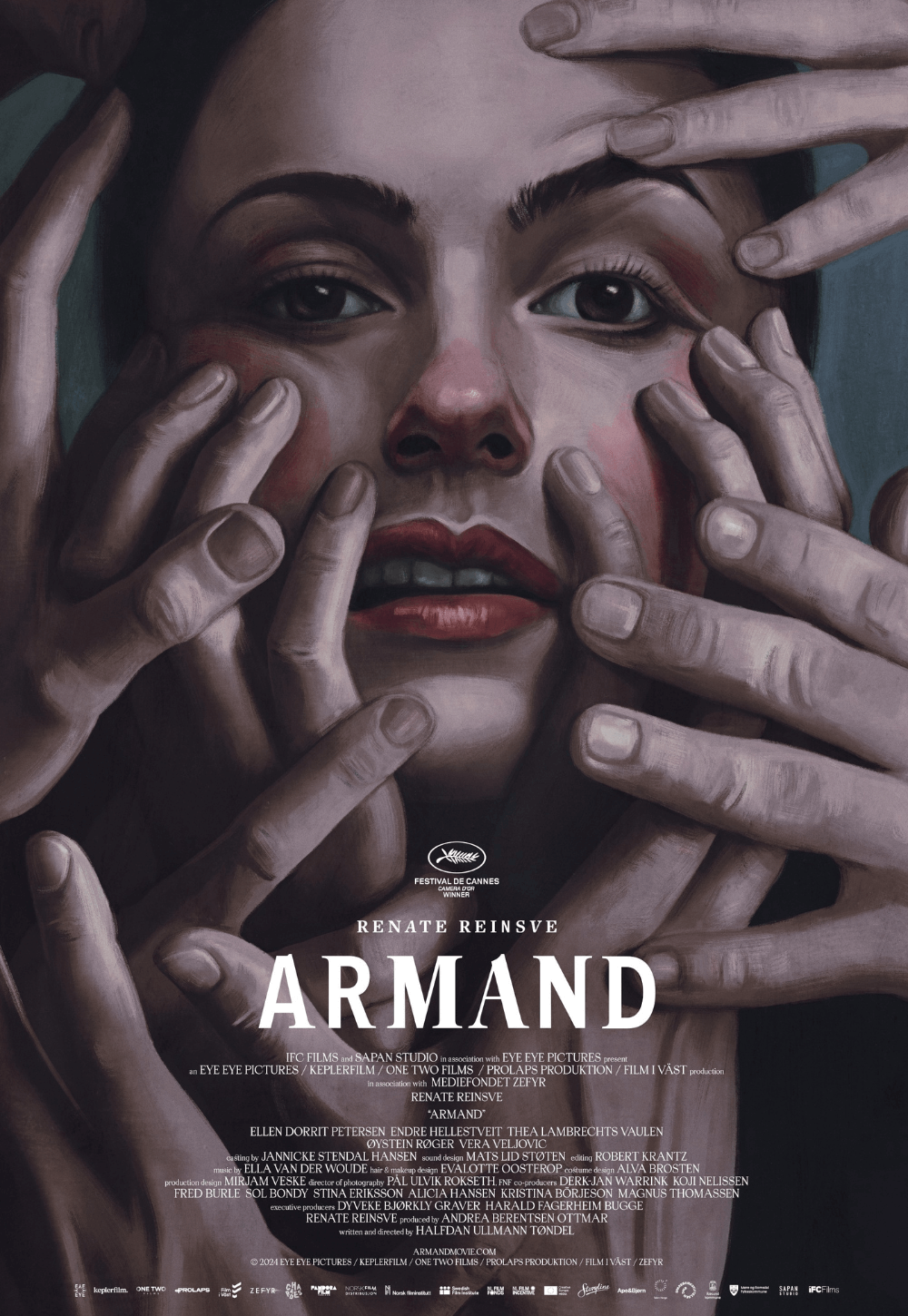

Reinsve, marvelous in last year’s A Different Man, gives a tour-de-force performance that’s bold and admirably weird. At one point during the conference, Elisabeth loses herself to uncontrolled laughter, earning harsh and exhausted looks from Jon’s parents and school mediators. Her outburst eventually transitions into tears, but Ullmann Tøndel allows the laughing to carry on long enough to take the viewer out of the scene. It’s one of those moments that begins funny, gradually becomes disturbing, and moves back into funny again before finally descending into emotional ache. Reinsve also proves June Diane Raphael’s theory that a woman’s hair often reflects her psychological state in the movies. Pulled suffocatingly tight into a ponytail at first, Elisabeth’s hair comes ever more loose as the story unfolds, suggesting her fraying mental state. Reinsve is bold and unflinching, particularly during a marionette-like dance in the school hallway or the nightmarish sequence of groping, greedy hands that perhaps reflect her (not unjustified) persecution complex, or her feeling that everyone wants a piece of her because she’s famous.

Ullmann Tøndel’s flourishes recall the surreal works of Luis Buñuel, whose films The Exterminating Angel (1962) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) influenced Armand in creating an impossible situation, heightened by sometimes absurdist touches. Yet, visually, cinematographer Pål Ulvik Rokseth doesn’t call attention to the exaggerated world. The muted, earth-toned color palette and grainy imagery have a faux naturalism that feels immersive, augmented by the ever-so-slight wobble of the handheld camera. Ullmann Tøndel and editor Robert Krantz deploy long shots, allowing the actors to writhe in uncomfortable scenes that alternate between funny and maddening. For all the film’s wilder flourishes and somewhat random asides, the director captivates by using his setup as a springboard to explore a variety of moods that can feel like an actor’s workshop or experimental theater.

However, Ullmann Tøndel’s screenplay doesn’t occupy one subjective perspective throughout the film. Whereas the eventual dreamlike sequences seem to pour out of Elisabeth, other scenes involve the dynamic between the inexperienced Sunna, the administrator Jarle (Øystein Røger), and mediator Ajsa (Vera Veljovic-Jovanovic), whose random nose bleeds disrupt the conference. Jarle has specific knowledge of Elisabeth; he taught her recently deceased husband, whose death is shrouded in uncertainty. Sarah and Anders have closer ties to Elisabeth than simply being parents with a child in the same school, and their familiarity with her personal life becomes equal parts motivation and mystery. The brief glimpse at the couple’s sex life felt, in this context, random. When it’s finally revealed what’s going on, the vague allusions to backstory throughout the film hardly lead to satisfying answers. This leaves Armand feeling unevenly cooked, with some parts overdone and others needing a few more minutes in the oven.

At last year’s Cannes Film Festival, Armand earned Ullmann Tøndel the Caméra d’Or for the best first feature. IFC Films picked up the release for US distribution, and it was also Norway’s entry for Best International Feature Film at this year’s Oscar ceremony—though, the film wasn’t nominated. Even so, those interested in Scandinavian film or seeing another terrific performance from Reinsve, one of today’s most promising actors, will come away intrigued but perhaps not satisfied. Maybe Armand is a treatise on the dangers of groupthink and mob mentality, or perhaps it’s a statement about how, if you look closely enough, everyone’s lives are chaotic and unhealthy in some respect—anyone could become the target of sanctimonious finger-pointers. It’s just as much about the consequences of an accusation as it is proof of an ambitious young director’s obvious potential.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review