Oh, Canada

By Brian Eggert |

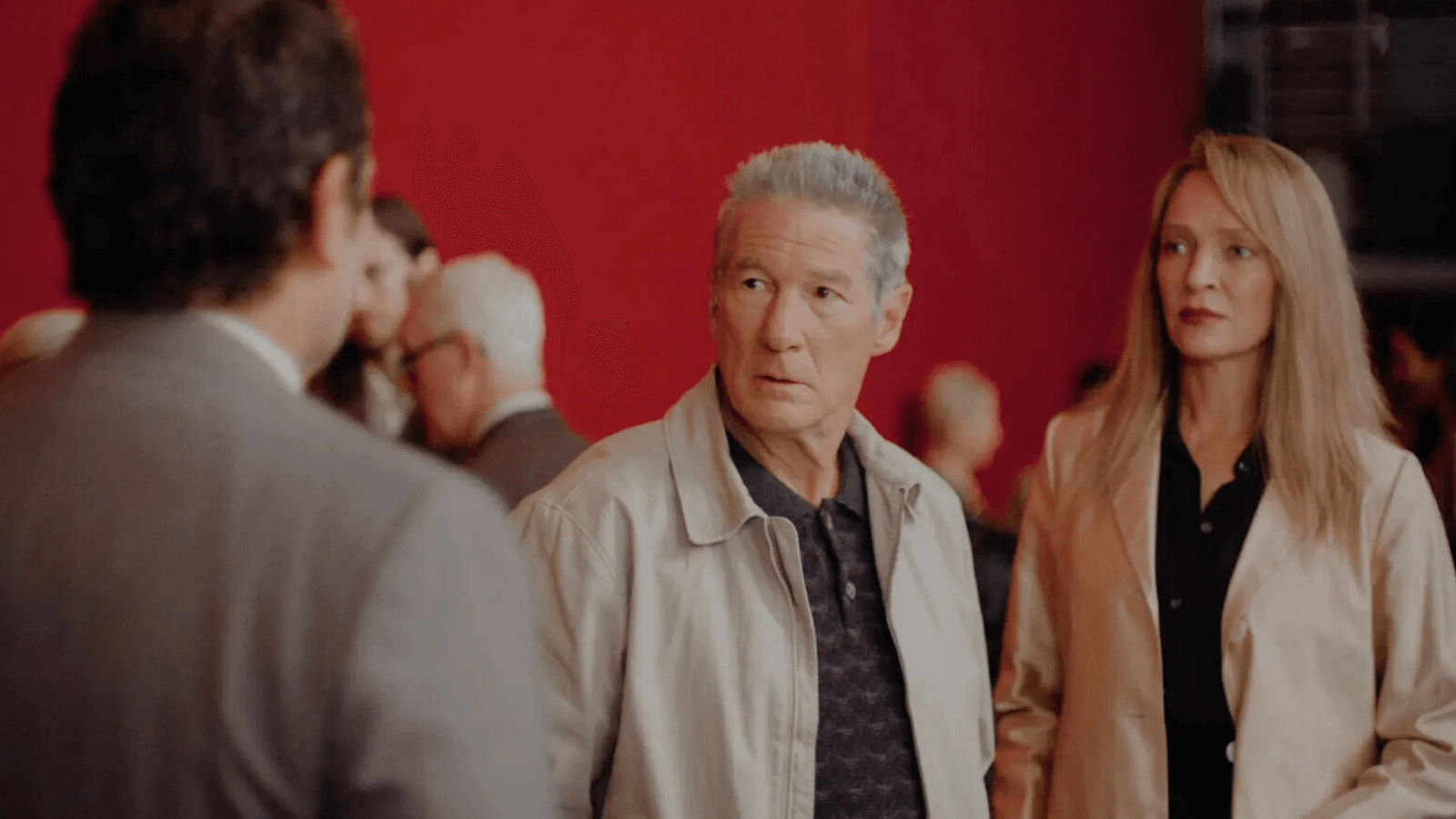

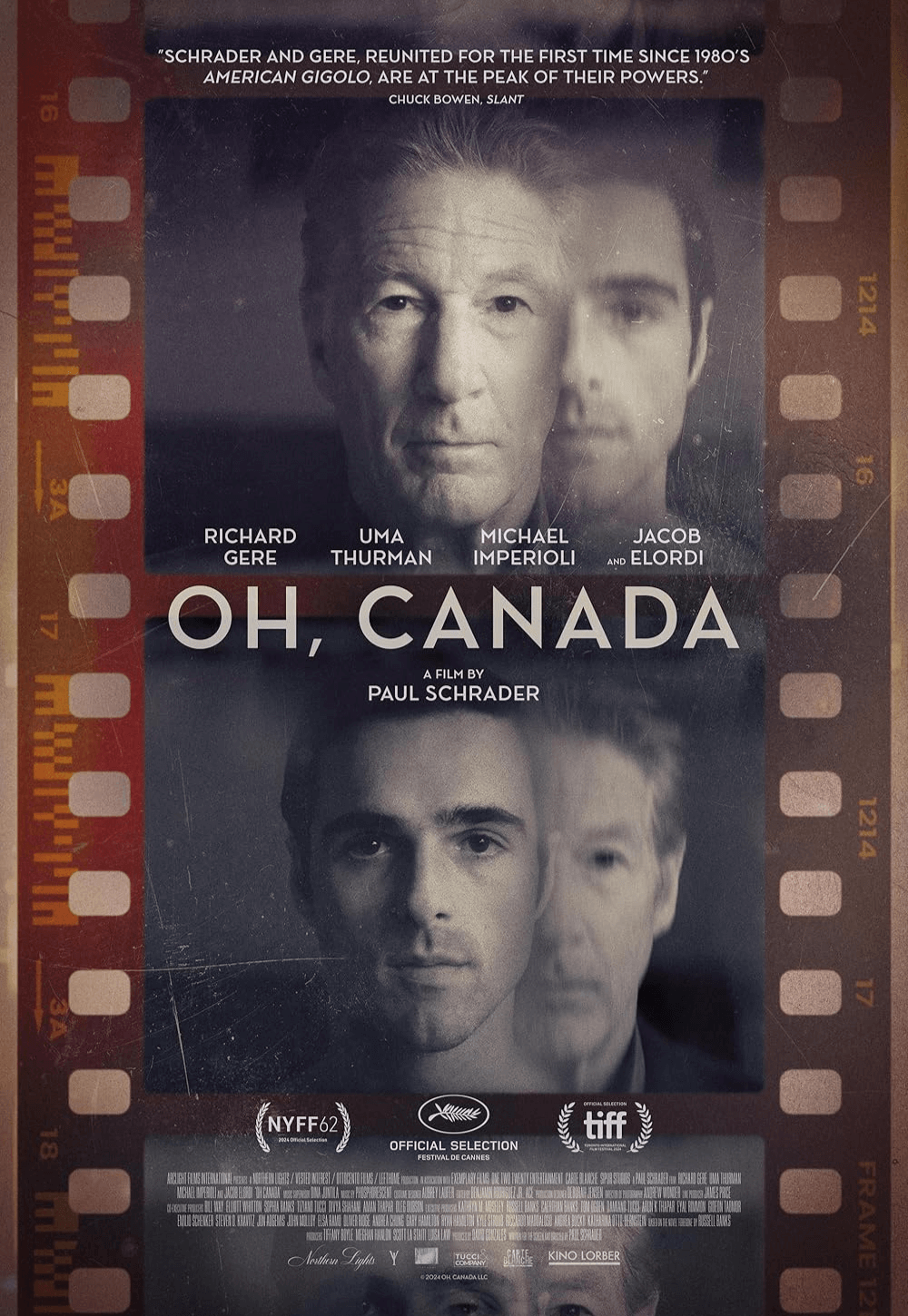

Paul Schrader wrestles with the interplay of art, reality, memory, truth, and mortality in Oh, Canada, a thoughtful if patchy drama about a documentary filmmaker’s last confession. But it’s not the sort of confession one might expect from Schrader, whose strict Calvinist upbringing shapes much of his work—from his frequent themes of repression and guilt to his confrontation of religious ideals. The tale involves the last interview of a highly celebrated documentary filmmaker who’s dying of cancer in Montreal. Determined to demystify his artistic legacy, Leonard Fife, played by an excellent Richard Gere in the actor’s first collaboration with Schrader since their 1980 pairing on American Gigolo, has earned a reputation as a leftist icon. He has a cabinet of shimmering awards and countless admirers. But he also has a mind full of images from his past, informed by films and stories of his much-mythologized reputation as a filmmaker. Schrader’s exploration of the character’s work, actions, and memories leads to a thoughtful investigation into whether we can separate the art from the artist, and also whether we should.

An adaptation of Russell Banks’ 2021 novel Foregone—with the name changed to the author’s preferred title—Oh, Canada marks the second time Schrader adapted one of the novelist’s books. In 1997, he made Affliction, based on Banks’ 1989 novel, and it remains one of his finest films. The two became friends, and Schrader dedicated this film to Banks, who died last year. Schrader, too, has admitted publicly, in his characteristically unrestrained manner of late, that he’s been grappling with health concerns that have put him in reflection mode. While he’s been on a critically acclaimed streak with First Reformed (2017), The Card Counter (2021), and Master Gardener (2022)—all films in which protagonists reconcile with their choices—Schrader’s latest seems the most personal. After all, the story involves an aged filmmaker examining his past amid physical ailments and mental decline.

When the film opens, Leonard’s former students, Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) and Diana (Victoria Hill), set up an interview space in their mentor’s home, vowing to deliver a sympathetic documentary about Leonard’s career, an “emblem of political filmmaking.” Leonard looks much like Banks did before the end, and he resembles Schrader now, with his hair thinning and white, and his face puffy and blotchy. His frequent throat clearing sounds concerning. Age has gotten to him, and his frustration has reached a limit. When a young production assistant gets him rigged for the interview, Leonard observes to himself, “She smells like desire itself.” He wonders, “What do I smell like, especially to a young woman?” At other times during the interview, he gets lost in confused thoughts, much to the concern of his younger wife, Emma (Uma Thurman). “He confabulates like he’s dreaming,” she warns, increasingly against the interview. But she also hopes to preserve his legacy of documentaries about US crimes in Vietnam, Canadian scandals involving sexual predators in the clergy, genocide against Indigenous people, and animal cruelty. But Leonard doesn’t care about his legacy; he remains committed to telling his truth.

Appropriately, Leonard’s interviewers use methods he pioneered—which, in real life, were developed by Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line, 1988). They set him up in an Interrotron, a device Morris conceived that allows the interviewee to look directly into the camera’s lens while seemingly making eye contact with the interviewer. “I made a career getting truth out of people,” Leonard observes, “and now it’s my turn.” The footage from his interview appears intermittently throughout the film, supplying a video equivalent of Schrader’s career-long interest in characters who journal and have internal monologues. More than just interview footage, Oh, Canada offers a cross-section of sources, such as voiceover from Leonard’s older self, narration by his adult son Cornel (Zach Shaffer), and a variety of visual sources, each presented in distinct formal execution. Schrader and cinematographer Andrew Wonder present memories in black-and-white widescreen footage, some present-day scenes in Academy ratio, and scenes from the past in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio in color.

However, these methods don’t adhere to a strict formal logic driving how Schrader presents scenes. It’s difficult to make sense of Oh, Canada’s use of objective flashbacks, unreliable narration, and aesthetics. Which of them represents the unvarnished truth? Is such a thing even possible? The lack of resolution is the point, but it’s jarring at times. Leonard’s persona has been tied up in his protest of the Vietnam War, when the “poisonous flower” of his reputation “first bloomed.” Leonard supposedly fled the United States for Canada as a conscientious objector. The truth is less romantic, involving an ignoble motivation to escape a marriage, fatherhood, and other responsibilities. In scenes from Leonard’s past, Schrader alternates between Jacob Elordi playing a younger version of the character and Gere’s version, as though today’s Leonard were transposing his older self over his younger self in his mind. (The actors don’t much resemble one another, so maybe Leonard always wished he was taller and looked different.)

Accented with delicate songs by Phosphorescent (Matthew Houck), Oh, Canada is less rooted in forbidden desire and bursts of violence than Schrader’s other films, nearly all of which dabble in extreme behaviors of some form. It’s unique in that respect, but it will almost surely be deemed less impactful, given that the director eschews his usual lurid sensibilities for something even more contemplative than usual. As the documentarian who knows he cannot tell the truth without the camera on, Gere transforms, disappearing into Leonard for one of his best performances in over a decade. Elordi also continues his streak of assured roles. But the varied, not-always-sound visual logic distracts from the dramatic heft behind this story. Oh, Canada feels incredibly personal as a reflection of Schrader and his friend, Banks, yet the director’s late-career period has produced far better films.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review