Short Takes

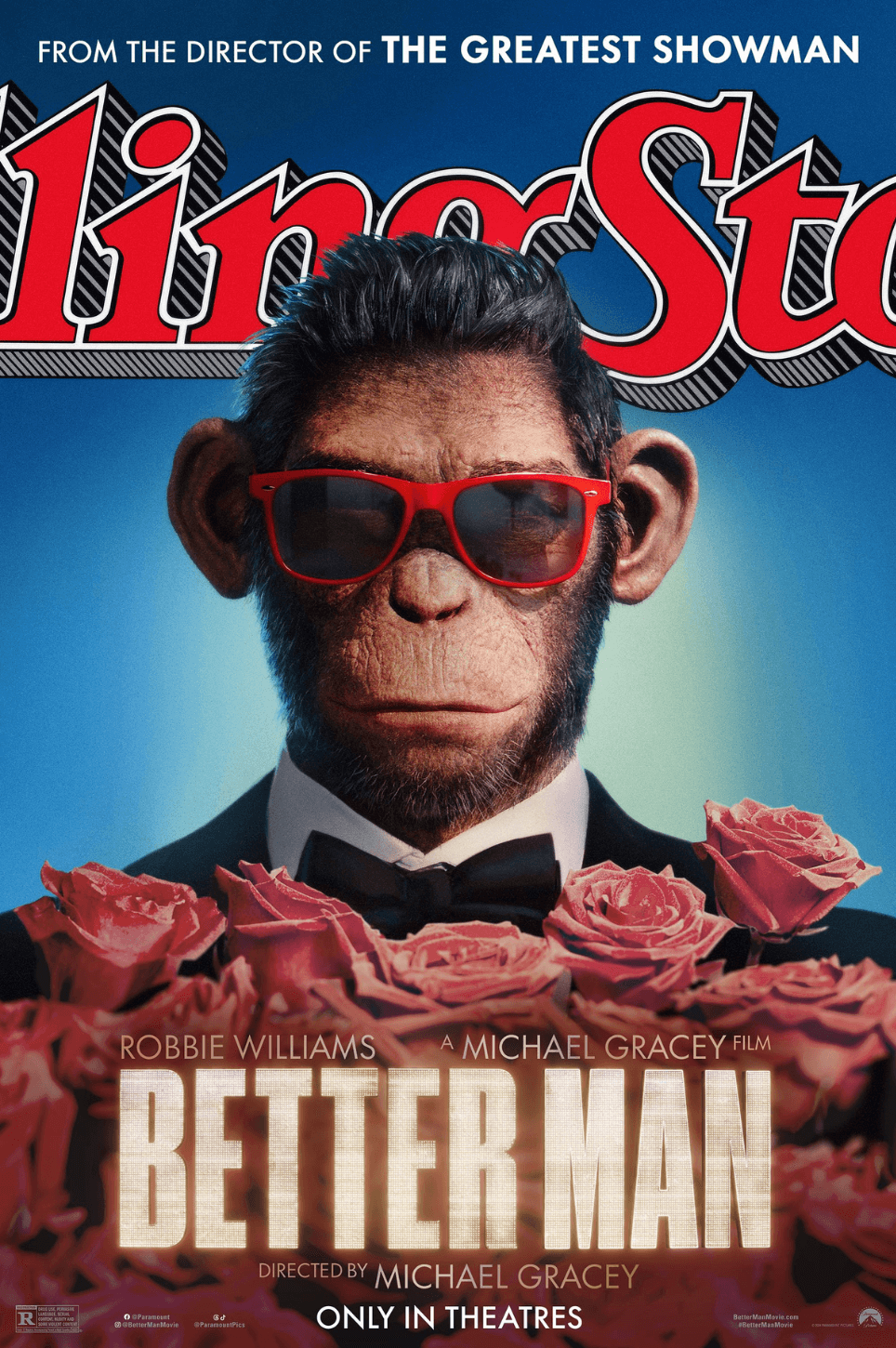

Better Man

By Brian Eggert |

Note: Paramount Pictures will release Better Man in theaters on December 25.

If, a few weeks ago, you had asked me to pick Britpop star Robbie Williams out of a lineup, I wouldn’t have been able to. Through some twisted set of circumstances, I have lived over four decades on this planet without ever hearing his name or being exposed to his music, neither through the boy band Take That nor his solo career. So, the conceit of his musical biopic, Better Man, where Williams appears throughout represented by a CGI ape—in a style recalling this century’s Planet of the Apes series—hardly landed with the same confronting force that I suspect a longtime superfan would have experienced. Instead, the film follows a similar trajectory as most biographies about pop stars. They all seem to rise from humble beginnings, persevere through their issues with their rocky upbringing to achieve fame, squander their celebrity on drugs and bad behavior, and then make a comeback after cleaning up their act. Better Man follows the same path, though the apish hook lends some novelty to this otherwise standard but well-made biopic.

Directed by Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman, 2017), the movie’s introspective yet critical approach harkens back to Bob Fosse’s self-portrait in All That Jazz (1979). Williams even compares his stage work to cabaret and references jazz hands. Supplying near-constant voiceover, Williams plays himself, acknowledging his faults in this warts-and-all recounting of his vile behavior, self-hatred, and vanity. The story covers his life from his fledgling days as a youngster, dreaming of being an entertainer on par with Frank Sinatra—a favorite of his unreliable father (Steve Pemberton), from whom Williams desperately wants approval—to his one-man show late in his career, where he predictably sings the Sinatra standard “My Way” in an expression of acknowledgment and acceptance. From start to finish, he behaves like an animal (a cheeky monkey, as it were), and that’s how he appears. Once the reasoning behind the digital gimmick becomes apparent, there’s not much more to consider. Though, it’s fascinating to consider how Williams’ selfhood remains so gleefully inflated yet self-deprecating that he agreed to this.

Gracey imbues the well-worn material with renewed through the ape device, leading to some dazzling visuals and impressive musical numbers—featuring hit songs that I, alas, had never heard before. When Williams makes a huge comeback at a massive concert, Gracey stages the sequence as an existential battle between the performer and hundreds of other ape-selves. Williams confronts them all in chaotic, bloody VFX combat. Indeed, this is a vibrantly and imaginatively made film, with cinematographer Erik A. Wilson capturing everything from grimy streets in the ’80s to glossy concert venues with textured detail and impressive production values. The filmmakers also recreate several famous moments from Williams’ life. When I looked them up afterward, they convincingly resemble the real thing (such as when Williams hilariously challenged Oasis frontman Liam Gallagher to a boxing match on live television). And the multiple credited editors keep the material as punchy as a music video. The most telling detail is that, even after Williams takes stock and learns important life lessons, he still sees himself as an animal, and thus so do we. However, none of it made me want to explore his music. Still, consider this a recommendation for fans.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review