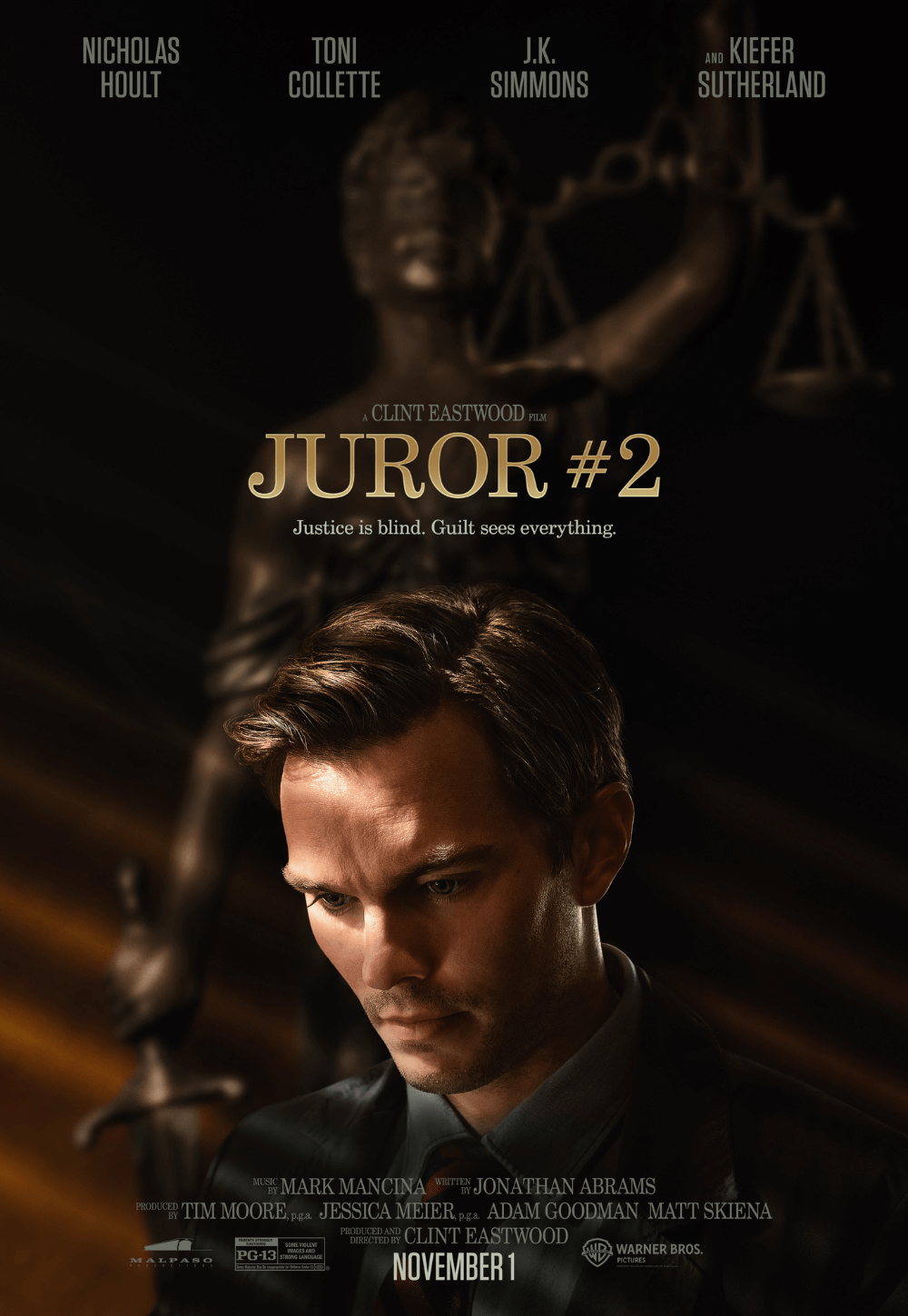

Juror #2

By Brian Eggert |

Clint Eastwood considers whether America’s justice system still works in Juror #2. This is the 94-year-old filmmaker’s 42nd film as director, and it’s among his most conventionally told stories. The screenplay by Jonathan A. Abrams plays like a Capra-esque drama confronting a broken system. It’s a story about how twelve flawed, self-interested jurors decide one defendant’s fate. The court assumes these people can put themselves aside and perform their duties in full consideration of the facts. But if you’ve ever served on a jury before, you’ve probably noticed that jurors remain, well, people. They’d rather be at home, caring for their families; at work, earning a living; or anywhere but in a deliberation room, debating with eleven other strangers about the case. They bring that animosity, along with personal motivations and biases, into their decision-making process, rendering the jury far from objective. And even while acknowledging this, Eastwood resolves that the universe will right itself—if not in the courtroom, then elsewhere.

Eastwood’s directorial career has been on a downswing over the last decade or so. Besides announcing his “last” screen appearance several times—on Trouble with the Curve (2012), then The Mule (2018), and most recently Cry Macho (2021)—many have speculated that Juror #2 will be his final project behind the camera. It’s neither a fitting end to a career nor is it an obviously personal project, but it aligns with his recent output. Looking over his oeuvre, Eastwood’s filmmaking and choice of scripts have declined, with everything after Hereafter (2010) fading into dullsville, whereas the previous decade showcased some of his finest work: Mystic River (2003), Million Dollar Baby (2004), Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), and Gran Torino (2008). But lately, Eastwood has been caught between true stories that lionize so-called American heroes and curmudgeonly crime dramas that cast him as a roguish old codger. They’re all sturdy productions, directed with the ease and experience of a seasoned master. And Eastwood once again delivers a technically solid product, well-shot by his regular cinematographer, Yves Bélanger, with a straightforward presentation.

Fortunately, Juror #2 also has an irresistible setup. In Savannah, Justin (Nicholas Hoult) receives a jury summons at the worst possible time. His wife, Allison (Zoey Deutch, underused), is pregnant and due in the coming weeks. The couple almost had twins before, but tragic circumstances led them to try again, and they’re desperate for everything to go smoothly this time. Justin shows up to court, sure he will convince the judge (Amy Aquino) that he should be dismissed from his civic duty, given his family situation. She asks whether he works. He does. She explains that jury duty takes place during the same hours as his job, where he would be if not in court, so he will not be dismissed. Justin doesn’t think to point out that he could probably leave work to rush Allison to the hospital should she go into labor, but he can’t leave the jury box if she needs him. Abrams’ script has a lot of moments like this, where the viewer can see a solution the characters cannot, and it becomes a constant hindrance to enjoying the movie. Nevertheless, Justin has an even better motivation to escape when he realizes that he may be responsible for the death at the center of the case.

The trial involves a defendant, James (Gabriel Basso), who’s accused of murdering his girlfriend, Kendall (Francesca Eastwood, Clint’s daughter). They were seen arguing in a dive bar. The argument continued outside into the rainy night. Kendall walked off, and James followed in his car. She died sometime later; her body was found below a bridge. Flashbacks show us that Justin, a recovering alcoholic, was also in the bar that night, grappling with his past. Although he didn’t drink, he drove home in the rain and hit something. He couldn’t see what. Assuming it was a deer, he continued home. Only upon learning the details of the court case does Justin realize that he may have inadvertently killed Kendall. Justin consults his lawyer friend and AA sponsor (Kiefer Sutherland), who warns that coming clean could land him a lengthy prison sentence with his record of alcoholism. So should Justin turn himself in, despite what it means for his family? Or does he allow another man to take the blame? Moreover, the latter option means that he hasn’t taken responsibility for his actions or adhered to AA’s Twelve Steps, which preach about taking moral inventory, asking forgiveness, and making amends. Not only must he contend with his legal obligations but also existential concerns as a recovering alcoholic, husband, and father.

Although the pitch for Juror #2 must’ve been easy, the screenplay’s clunky execution of this concept proves disappointingly generic. A predictable cross-section of banal character types populates the jury room, recalling a substandard version of 12 Angry Men (1957). There’s the angry guy with prejudices (Cedric Yarbrough), the savvy ex-cop (J. K. Simmons), the foreperson with mom energy (Leslie Bibb), the youngster (Drew Scheid), the senior citizen (Rebecca Koon), and so on. Each of them is one-dimensional. Outside, the no-nonsense prosecutor (Toni Collette, in a reunion with Hoult, her costar in 2002’s About a Boy) worries more about a district attorney election than investigating the facts of the case, and her arguments rely on largely circumstantial evidence. The public defender (Chris Messina) believes his client is innocent. Indeed, the clichés and simplistic characters run rampant through Abrams’ writing, and the specifics of the case aren’t convincing, taking what might’ve been a good potboiler and delivering an unsubtle morality tale.

Warner Bros. gave Juror #2 a truncated release in fewer than 50 theaters. This decision is baffling given Eastwood’s proven track record and the material’s resemblance to a Southern-accented John Grisham legal yarn—the sort of commercially successful mid-budget thriller for adults that hasn’t been commonplace since the 1990s. No matter how unfair that feels, it’s far from one of Eastwood’s best. It has an implausible old-fashioned quality, as though its morality was guided by the Hays Code, complete with blunt-force symbolism and a protagonist who must answer for his wrongdoing. As Juror #2 raises questions about justice and due process, Eastwood visualizes them with the presence of a Lady Justice statue whose scales sway in the wind. Even though the director seems to question the effectiveness of self-interested jurors, the story ultimately reinforces faith that justice will be done in the last shot. The system works, sort of. If mildly cynical, it’s still a conservative viewpoint, typical for Eastwood, that abandons many of the complex issues at stake throughout the rest of the drama. And yet, by ending the movie a few seconds earlier than where he did, Eastwood might’ve left audiences with more to talk about.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review