The Order

By Brian Eggert |

“In ten years, we’ll have members in the Congress, in the Senate. That’s how you make change.” That’s a line spoken by the head of a white supremacist group in The Order, and it’s chilled me to my core with echoes of today. Detailing a real-life investigation into domestic terror in the Pacific Northwest, Australian director Justin Kurzel’s thriller charts the activities of a neo-Nazi group that robs banks, armored trucks, and adult bookstores to fund their organization. Their ultimate goal: insurrection, revolution. Based on events that occurred in the early 1980s, this story has implications that reflect today’s political climate. Though, it’s already been the subject of other films, most notably Costa-Gavras’ engaging but dramatically absurd take, Betrayed (1988). In his confrontation with the violence in America’s past and present, Kurzel’s grim and disturbing treatment has the texture of cop thrillers from the 1970s, with spare, alienated characters facing horrible, real-life crimes. It’s an urgently germane and bleak look at a rotten facet of American identity, one that aligns with the filmmaker’s investigations of violence in his own country.

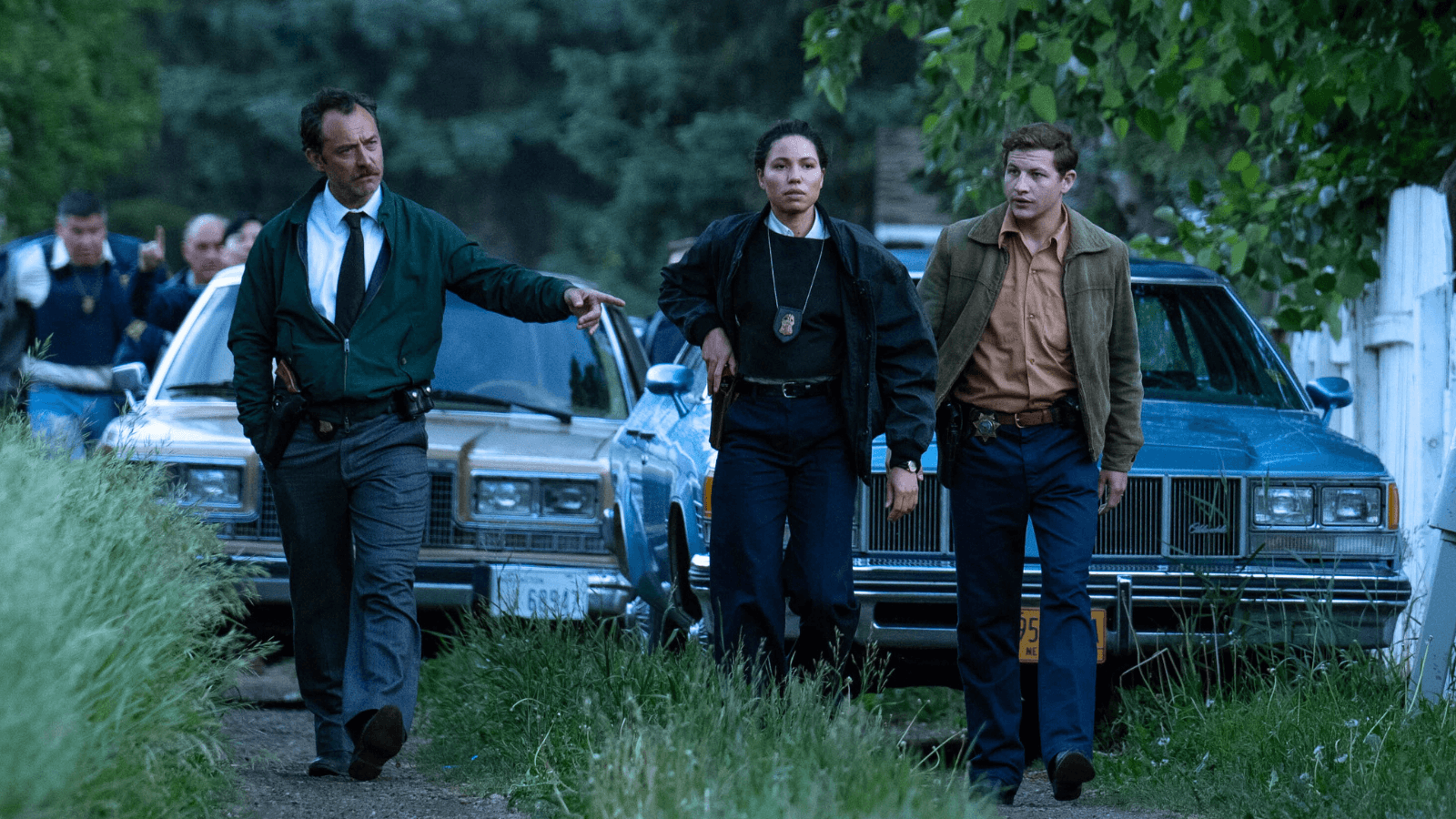

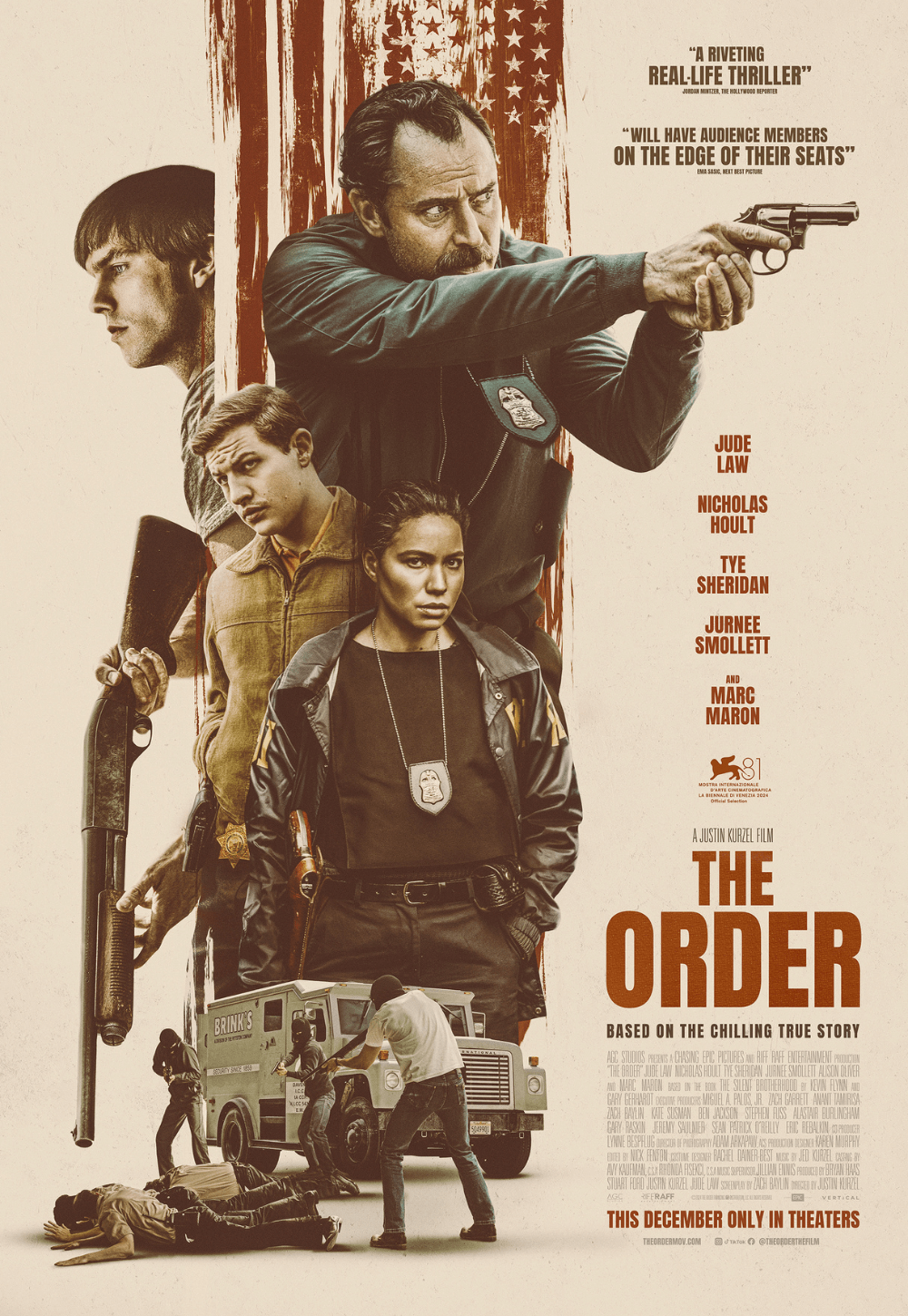

From Black Legion (1937) to BlackKklansman (2018), many films have confronted how hate groups are hardly new developments in the United States. Kurzel’s film draws from The Silent Brotherhood, Kevin Flynn and Gary Gerhardt’s 1989 nonfiction book, adapted here by screenwriter Zach Baylin (2021’s King Richard, 2024’s The Crow). This loose procedural follows an experienced and grizzled FBI agent, Terry Husk (Jude Law), who has taken on the Sicilian Mafia and KKK in the past. Arriving in the rural environs of his sleepy new post, Husk notices “white power” signs displayed and finds that local authorities have turned a blind eye. That is, except for Jamie Bowen (Tye Sheridan), a good cop who recognizes the danger the Aryan Nation poses. He knows some of them all too well; they’re his neighbors. Jamie has been quietly gathering intelligence until he could talk to someone like Husk, willing to take on the threat with help from another good cop, Joanne Carney (Jurnee Smollett).

The Order alternates between Husk’s investigation, which unfolds over several years, and the rising white supremacist crime wave to fund their infrastructure. It’s overseen by Bob Mathews (Nicholas Hoult), a radical who defies his local Church of Jesus Christ—Christian, an actual organization founded by a KKK member. Mathews wants less talk, more action. He takes instruction from The Turner Diaries, William Luther Pierce’s 1978 book about a white supremacist revolution that leads to the systematic extermination of Jews, people of color, and liberals. The book would inspire dozens of hate crimes, including the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and the assassination of radio personality Alan Berg—which is depicted here with Marc Maron portraying Berg. Mathews and his acolytes use Pierce’s text like a guidebook. Although they have family barbecues and look normal enough, they also teach their kindergarten-age children how to shoot automatic weapons, call the federal government a “cult,” and rob banks to fill their war chest.

Kurzel is no stranger to stories about violence infesting rural areas. His debut feature, The Snowtown Murders (2011), considers a notorious case from the 1990s that found three cohorts leaving a dozen victims in their wake. A decade later, Kurzel made Nitram (2021), a drama starring Caleb Landry Jones, about the Port Arthur mass shooting in 1996. Both films depict how extremism builds in the mind and leads to an outpouring of violence. Similarly, Kurzel explores actual events in Baylin’s screenplay, though they’re far from embedded into the American historical consciousness. The American media has a tendency to downplay and under-report on the spread of domestic terrorists and white supremacist groups, minimizing threats as isolated incidents given the culture’s aversion to extremism at home, in some cases because of political biases. For some outlets, it’s a more attractive prospect to report on immigrants or terrorism in other countries than our own.

America’s unwillingness to hold a mirror up to the uglier aspects of its identity remains a central theme in The Order, with the experienced Husk having sized up men like Mathews before. In a transformation that reminds us Law is one of today’s most talented actors, his intense, gum-chewing performance, behind a weathered face, thick mustache, and macho swagger, features lines where Husk notes how white supremacists and gangsters are always looking for someone to blame. They have a chronic condition—a thin skin that prevents them from looking inward or taking responsibility for their lives. They’re puritanical about everyone adhering to their worldview because they’re “too inept to get by in the world” without creating their own rules. Through Husk, Bowen, and Carney, the director and screenwriter of The Order show contempt for and dread over these detestable groups, while they acknowledge this represents one such faction among many. Hoult supports this by disappearing into his role, delivering a superb and convincing look at the kind of person who follows an extremist, hate-filled ideology.

As usual, Kurzel’s visual treatment relies on crisp imagery, clear action, and location shooting, with Alberta standing in for Washington state. Aussie cinematographer Adam Arkapaw, who has shot several Kurzel features, works alongside production designer Karen Murphy to create an authentic-looking environment. Editor Nick Fenton builds momentum by cross-cutting between Husk and Mathews, establishing a years-long game of cat-and-mouse. The action sequences, including a bank robbery and a couple of armored truck heists, crackle with energy. The Order doesn’t offer much by way of entrenched characterizations or dimensionality. What it does well, however, is explore a disturbing chapter in American history with grit and honesty. Made even more unsettling by the growth and reemergence of such groups in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, the film remains shocking, eye-opening, and portrays a disturbing reality that has become more common than most would care to acknowledge.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review