Wicked

By Brian Eggert |

Wicked, the big-screen adaptation of the beloved Broadway musical by Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman, finds new relevance as a Hollywood production. The first of a two-part cinematic event, with the second half arriving late next year, director Jon M. Chu’s lovely and colorful movie supplies a commentary on this moment in the United States’ sociopolitical landscape. It’s a story about the tragic implications of judging someone for their differences; about suppressing knowledge to maintain power; about how control is achieved through popularity, not authenticity or a commitment to facts; and about duplicitous leaders who deceive their citizens to preserve their positions of authority. Watching Wicked, its uncanny parallels with today’s book bannings, xenophobic fearmongering, and authoritarianism felt urgent and vital. Doubtless, Chu and screenwriters Holzman and Dana Fox recognized how the material corresponds with this cultural moment, but they resist overemphasizing the association, allowing Wicked to be the glossy song-and-dance spectacular fans expect.

Before we go any further, dear reader, I must confess something. I have never seen the musical Wicked, neither performed live nor prerecorded. Although I have heard the songs “Popular” and “Defying Gravity” in passing, and countless admirers have shared their love of the musical, I have never seen a production. Sitting down for the movie, I knew only the broad strokes of the story—a postmodern spin that reconsiders the Wicked Witch of the West as a tragic, misunderstood figure, while Glinda the Good Witch of the North comes off as a mean girl in a parable for intolerance and discrimination. Given that most of us know the Wicked Witch’s still-horrific “I’m melting!” fate from The Wizard of Oz (1939), the story furthers the modern trend of repurposing classic fiction by demystifying and rethinking favorite tales from a new perspective. In that sense, I could guess where Wicked would end up, and the first images—a puddle of water, an empty witch’s hat, some smoke linkering where she dissolved—offered no surprises.

Still, the movie supplies a case study in adaptation and revision. The source material, of course, harkens back to the 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz. This perennial classic has maintained a place in the cultural consciousness more than any other Golden Age production. That Technicolor landmark was based on L. Frank Baum’s series of fourteen novels, starting in 1900 with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. For decades, the original film has remained an essential American masterpiece whose iconography and dialogue have penetrated an immeasurable number of other films, television shows, and songs—to say nothing of other revisionist takes, such as The Wiz (1978), Return to Oz (1985), and Oz the Great and Powerful (2013). However, Wicked is the brainchild of author Gregory Maguire, whose deconstructionist book, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, was published in 1995 and followed by three sequels. Maguire’s text supplied the source material for the 2003 stage musical. So, to sum up, Wicked’s origins include multiple books, a lauded movie, and a Broadway sensation, and each has its distinct interpretation and take on the material.

Chu’s iteration conforms to today’s mode of blockbuster filmmaking. Early on, Wicked indulges in sweeping computer-generated shots over Oz, recalling moments from every studio tentpole of the last two decades. These give way to several talking CGI animal characters—a dog doctor, a bear nurse, a goat teacher, etc.—and an actionized climax saturated in digital effects. Many sequences in Munchkinland and the Emerald City have a more tactile feel, with production designer Nathan Crowley (whose work includes last year’s Wonka) delivering a similar blend of elaborate sets and green screen work. Costume designer Paul Tazewell’s efforts result in gorgeous costumes that look best when rendered in actual fabrics instead of their periodic, artificially wistful computer counterparts. Likewise, cinematographer Alice Brooks, who also worked with Chu on Jem and the Holograms (2015) and In the Heights (2021), delivers a bright and cheery-looking aesthetic, even capturing some imagery that feels instantly iconic. Though, the obvious CGI-ness of Wicked often prevents the drama from feeling as substantial as it could.

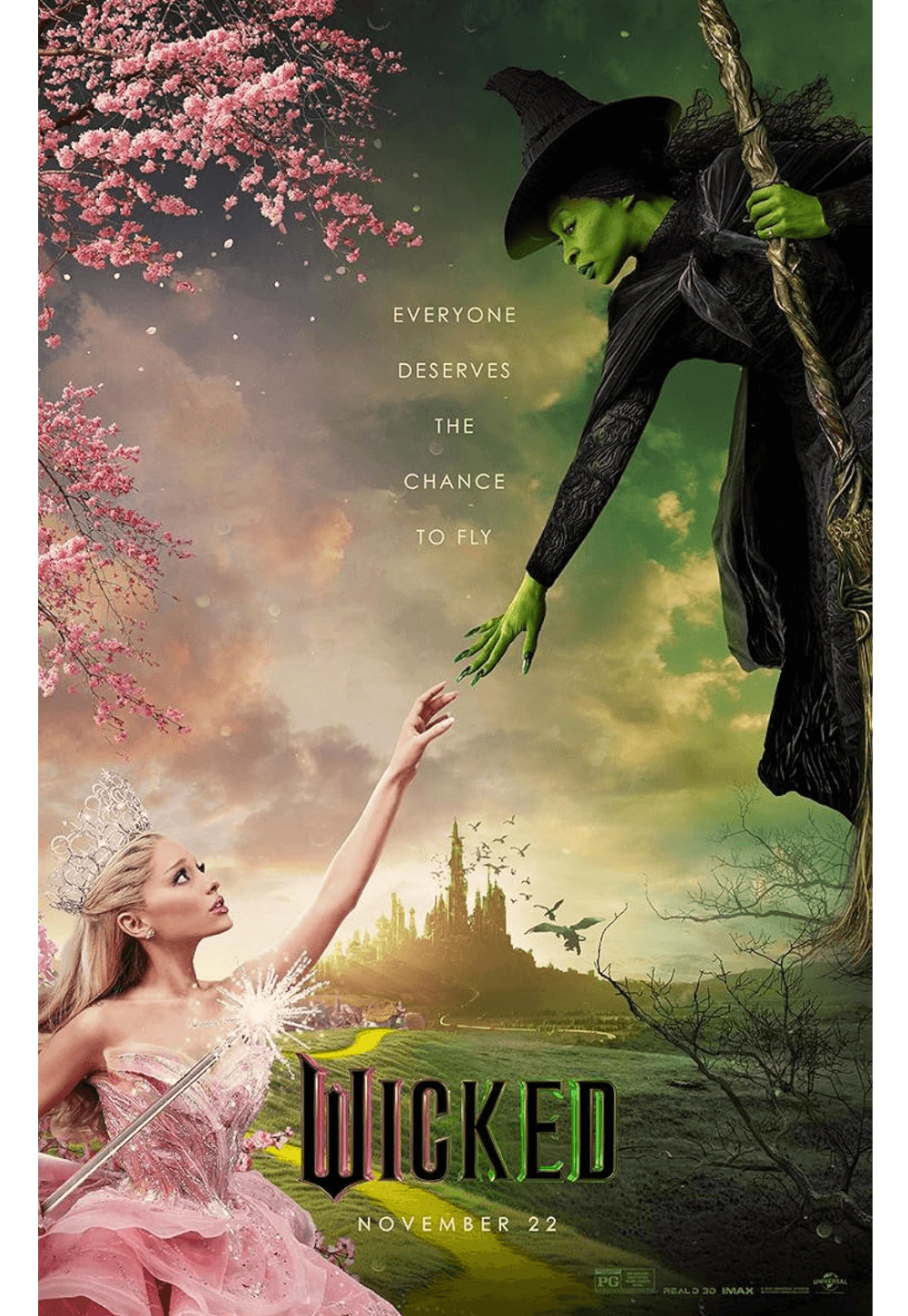

Much of the story plays out like high-school clique fare set at the Hogwarts-esque Shiz University, with an ensemble cast in their 30s playing teens. There, Elphaba (the great Cynthia Erivo), an intelligent, green-skinned outcast from a prominent family, must room with Galinda (Ariana Grande), an entitled pink elitist from a privileged background. Constantly judged by her colorist classmates, most of whom are unlikable, Elphaba has telekinetic abilities that draw the attention of Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh), the headmistress who plans to teach her magic. Nessarose (Marissa Bode), Elphaba’s paraplegic sister, also feels like an outsider because of her wheelchair. There’s a hunky prince, Fiyero (Jonathan Bailey), who embraces “The Unexamined Life” and nestles up to Galinda before realizing Elphaba has more to offer. And while a conflict worthy of an ’80s high-school movie unfolds—complete with a school dance sequence that brought to mind the one in Can’t Buy Me Love (1987)—another storyline involving a conspiracy to suppress and subjugate talking animals leads to a revelatory encounter with the Wizard (Jeff Goldblum). He’s a Walt Disney-esque character, living in a hollow Magic Kingdom. But there’s also a hint of Charlie Chaplin’s character from The Great Dictator (1940) in him, evidenced when Oz plays with a moon balloon in a faux godlike manner.

Dread and oppression loom beneath the surface of Wicked’s narrative. The land of Oz feels like the Weimar Republic before the Nazis took over Germany, or more to the point, this moment in America. Suppression, propaganda, intolerance, and fearmongering run rampant in the animal-centric storyline. Some shadowy force—and it isn’t difficult to guess who’s behind it—has quietly removed animals from key positions to stop “seditious animal activity.” The authorities detain animals and literally take away their voices by placing them in cages. The metaphor could be applied to the Holocaust or immigrants detained in US holding centers. No matter the case, the political forces in power stoke the public’s fear as a method of control. All of this might seem like heavy material for an escapist musical that uses more silly words than Mary Poppins (pronouncifying, scandalocious, graditution, hideodius, astoundifying, et al.). Nevertheless, Wicked engaged me with its universal yet timely ideas. And while one might assume these germane themes were designed to comment on contemporary politics, they originated in Maguire’s book and carried over into the Broadway show. If they’re familiar, it’s because history is repeating itself.

The enthusiastic fanbase surely knows all the story beats by now, leaving the magic to the details in the production and performances. Central is Erivo, who carries the film’s heart in her expressive eyes and monumental voice. She’s perfectly cast, full of tenderness, humanity, and passion, so much so that it’s difficult to imagine her version of Elphaba twisting into someone who wants to capture and kill Dorothy and Toto. She plays Elphaba’s dramatic rise beautifully, and her pivotal scenes in the finale brought a tear to my eye. Grande never quite looks the part of a blonde Queen Bee; despite appearances, she occupies the bubbly role well, creating a Galinda (later Glinda) whose brief moments of sympathy and ridiculousness don’t quite overshadow her shallowness and self-absorption. The supporting cast is strong, particularly Yeoh, but also Peter Dinklage as the voice of a persecuted goat, Doctor Dillamond, who teaches the sort of history Oz wants out of schools—the unvarnished kind.

The question that has nagged at many is this: Why two parts? The stage version lasts two hours and forty-five minutes, which is about the length of this (overlong) movie. Why did the producers feel the need to pad the material to break up the story? The answer is simple. Wicked will make loads from ticket sales, merchandising, and cross-promotional deals. The intellectual property is a gold mine. And doubtless, the executives in charge realized the only thing better than a blockbuster movie adaptation of Wicked is two of them. This financial imperative means the filmmakers have dragged out the story. Several sequences luxuriate in CGI landscapes, and others feel like repetitive clichés from a teen comedy. The dances go on a little too long. Every point is made at least twice. Wicked can sometimes feel bloated, and I wanted the movie to get on with the story already.

Even so, I was invested in Elphaba and her journey. This is a classic melodrama, driven by themes of class and power. But also, it’s about critical thought—it raises questions about the notions of good and evil, authority, and so-called truth. It wants people to open books and read them. It hopes people will question their leaders and not take them at face value. Plus, the songs are catchy, the production spares no expense, and it’s fun. If my enthusiasm feels at all restrained, it’s partly because Wicked too closely resembles a prototypical Hollywood blockbuster, from its butt-numbing runtime to its over-dependence on CGI. But it’s also because I’m reviewing half of a movie. I had the same noncommittal response immediately after Denis Villeneuve’s Dune (2021), another story bisected for financial reasons. Fortunately, Wicked’s second half has not only been greenlit but shot, leaving moviegoers assured that the saga will continue. This is a gamble that, in cases such as the two-part Harry Potter finale or Dune, has paid off well; in other cases, including Kevin Costner’s Horizon flop from earlier this year, the episodification of cinema has resulted in critical and commercial disaster. But it’s difficult to imagine Chu and company not sticking the landing. I remain cautiously optimistic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review