The Brutalist

By Brian Eggert |

When Rembrandt first unveiled The Night Watch (1642) to members of the civic guard who commissioned the painting, they barely recognized themselves. Rembrandt’s heavy use of shadows, broken only by touches of dramatic light, rendered his subjects almost imperceptible. He had tried something new; they wanted something conventional. But history remembers Rembrandt and the painting, not the members of the Dutch militia who paid for it. A similar tale to Rembrandt’s The Night Watch unfolds in The Brutalist, Brady Corbet’s third feature. Exploring the relationship between an artist and the patron who hires them, this sweeping immigrant story chronicles thirty years in the life of László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Hungarian-Jewish architect who survives the Holocaust, emigrates to the United States, and earns a monumental commission under a wealthy industrialist. Corbet and his regular co-writer, Mona Fastvold, consider how the immigrant experience is tantamount to a revolutionary artist’s work. Although both introduce a new element, which many greet with confusion, contempt, and even antipathy, they transcend the initial reaction over time and soon become inextricable from the fabric of the culture.

Corbet’s sprawling American saga is set in the mid-twentieth century, yet its scope reveals time as the great equalizer. Corbet and Fastvold construct a humanist story about the false promise of the American Dream for László and many like him, who escape their peril and land in the arms of a country that treats them like subhumans. Just as László feels unwelcome in America—signaled by the early image of the Statue of Liberty shown in chaotic, upside-down visuals, echoing the film’s theme about capitalism’s corruptive influence—his Brutalist architecture, although celebrated in his Budapest home and most of Europe, clashes with the reserved and artless class of elites in Pennsylvania. To whatever extent America overlooks the buildings László designed during his lifetime, his work survives and outlasts dissenters. Given this, the film also feels urgent in today’s climate of intolerance toward migrants. While the Statue of Liberty declares, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” politicians and bigots have other ideas. With this vile strain of xenophobia spreading, an immigrant story set in the US cannot help but be political.

Of course, László Tóth is a fictional architect, informed by actual figures such as Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Ernő Goldfinger. Above all, Corbet and Fastvold draw from the life of Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer, who, like their protagonist, studied at the Bauhaus school and designed furniture made of tubular steel and leather straps. According to the press notes, the filmmakers became fascinated by how Brutalism reflected the 1950s postwar era, emphasizing austere concrete surfaces and minimalist designs while downplaying the importance of decoration and traditional beauty. The imposing physicality of most Brutalist structures echoes the stripped-down but no less impactful spaces. The elegant designs often have an unwelcoming aesthetic, marked by geometric shapes and honesty about the materials used to build them. These structures echo the loss of the previous decades in their outwardly utilitarian appearance, serving as a poetic, if also restrained, expression. It’s as though the trauma of the Holocaust and World War II had cut away any need for superfluous flourishes, leaving only the bare essentials of design. In its day, Brutalism proved too modern, too cold, and too conceptual for many.

Corbet likens this style of architecture to immigrants in his film, which centers on László, who was separated from his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) during the war. She remains in Europe with their niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy). When László arrives in the United States, he connects with his cousin, Attila (Alessandro Nivola), a furniture store owner in Philadelphia. While there, he lands a job renovating the library of Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a voracious and ultimately monstrous industrialist. Harrison is initially enraged that his adult children, Harry (Joe Alwyn) and Maggie (Stacy Martin), would allow immigrants into his home. However, as the film progresses, and he realizes László has quite a reputation in Europe, he hires László to construct a massive community center in honor of his late mother. The proposed structure will contain a library, gymnasium, theater, and chapel, but László’s visionary design tests Harrison’s resources and commitment to the project. While giving László a life-changing contract, Harrison uses his connections to arrange for Erzsébet and Zsófia to move to the US.

Far from being a selfless benefactor, Harrison may find László “intellectually stimulating,” but his cruel streak runs deep. At one point, he regales László with a disturbing story about how he savored humiliating his grandparents when they asked for a handout. Harrison’s money and appreciation of László’s work don’t overshadow what, not long after their arrival, Erzsébet and Zsófia find to be true: the Van Burens are just plain awful. Harry takes after his short-tempered and ferocious father, not just because they’re both predators (and at least one, likely both, are rapists). They both feign generosity but remain entitled WASPs who react sharply, even maliciously, when challenged. They “tolerate” László. For his part, László, cold yet weary-eyed, still reels from his trauma and displacement during the Holocaust, falling into bouts of self-destruction through drug addiction and artistic obsession. This factors into his work in ways not immediately apparent. Elsewhere, the Oxford-educated Erzsébet and mute Zsófia prove independent and intelligent, with the former almost supernaturally attuned to her husband’s mind and experiences. But it’s Zsófia who first recognizes the unwelcoming toxicity of American culture and resolves to move away to the newly formed State of Israel. Soon enough, Erzsébet agrees: “This whole country is rotten.”

With The Brutalist spanning three-and-a-half hours, including an overture, 15-minute intermission, two chapters, and an epilogue, Corbet obviously had grand designs for his third feature. His first two films were no less ambitious, deploying some of the same structural devices through chapters and segmentation. The Childhood of a Leader (2015) follows a young American boy in France whose petulance and disdain for authority drive him to become a fascist leader. Next came Vox Lux (2018), a story of celebrity and extremism that has lingered with me longer than my initial review might’ve suggested. Corbet began his career as an actor, working with iconoclasts such as Gregg Araki (Mysterious Skin, 2004), Michael Haneke (Funny Games, 2007), and Lars von Trier (Melancholia, 2011). He stopped acting after 2014, a year in which he appeared in films for Bertrand Bonello, Noah Baumbach, Ruben Östlund, Mia Hansen-Løve, and Olivier Assayas. Some actors work their entire careers without building such a list of credits. Evidently, he learned a thing or two from these masters and applied those lessons to his work, delivering three uncannily assured films.

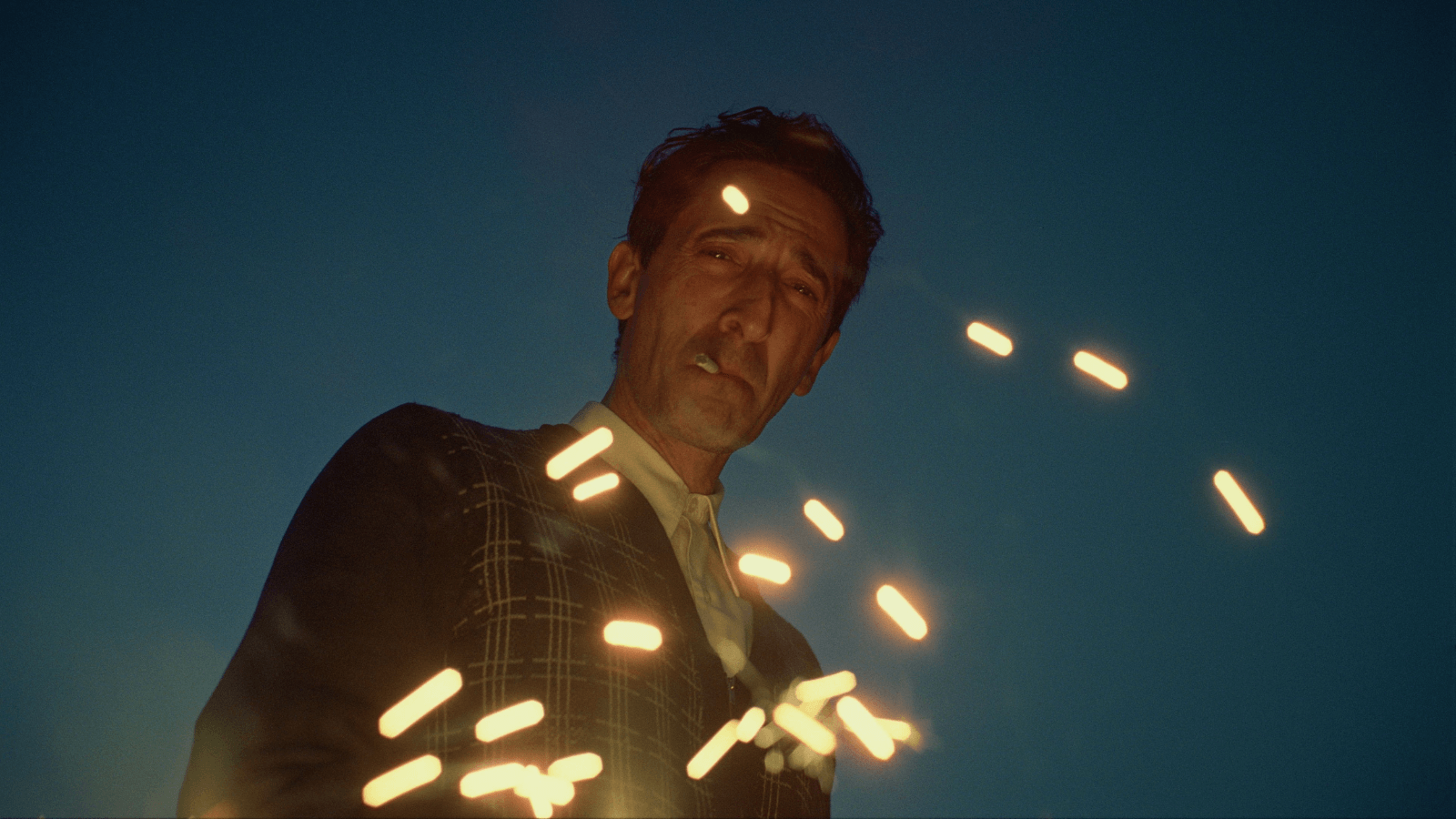

The Brutalist is an unmistakable step forward in Corbet’s work: It’s a masterpiece. His severe geometric narrative shape is only matched by the thematic depth that informs every aspect of the production. Take his choice to shoot on VistaVision, a now-obsolete but no less glorious widescreen 35mm format developed in the 1950s. Invented around the time The Brutalist is set, VistaVision offers crisp and textured imagery on celluloid courtesy of cinematographer Lol Crawley, whose lighting and lens choices range from painterly to transportive to expressive. There’s always something fascinating aurally, as well, including Daniel Blumberg’s complementary score, radio news broadcasts, and Corbet’s tendency to place audio from educational films about drugs and sex over László’s darkest moments. To be sure, Corbet’s approach is far from classical. Alongside editor Dávid Jancsó, the director creates impressionistic montages and deliriously scrambled sequences, such as one where László, lost in a frenzy of jazz and drugs, spirals out of control with his friend Gordon (Isaach de Bankolé). The film also features archival footage of construction and steel work that, along with a smattering of vintage pornography, makes The Brutalist feel like a multimedia text doubling as a human epic—one that races by despite the lengthy runtime.

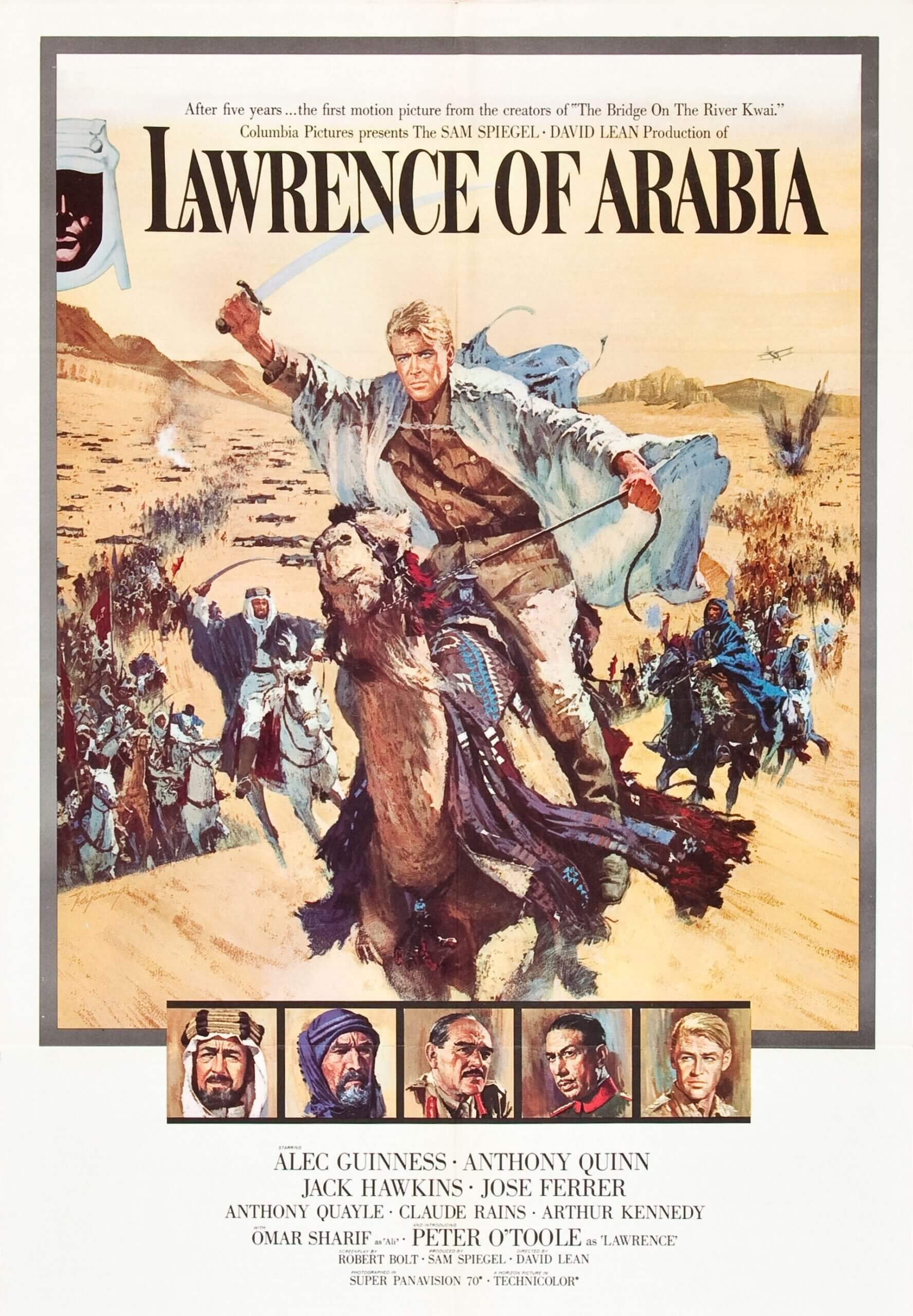

For his efforts, Corbet won the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 2024 Venice Film Festival, and it’s easy to see why. Even while working on a large canvas, he allows for ambiguity and equivocations without ever sacrificing his main character’s entrenched psychology. This is an approach David Lean took in Lawrence of Arabia (1962)—which established the question “Who are you?” early on, only to leave the question unanswered nearly four hours later—and that built-in uncertainty about the film’s subject gives way to a lasting curiosity that will serve The Brutalist well beyond an initial viewing. Corbet is also an incredible director of actors. Brody, whose mother was a Hungarian refugee and photographer, hasn’t seemed this invested in a role since his Oscar-winning turn in The Pianist (2002). Pearce is villainous and arch but no less effective, and Jones has never been better. However, the performances remain another in the film’s many components that point in the same direction—a message that difference is temporary. Change is natural and unavoidable.

Miraculously, Corbet tells such an expansive story over 215 minutes yet the destination is just as significant as the journey. Other assessments of The Brutalist have complained that the epilogue leaps to Venice in 1980, complete with traces of analog video and pop music. The aged László appears in a wheelchair, and the now-grown Zsófia (Ariane Labed) addresses attendees of a retrospective of her uncle’s work on his behalf. The style almost completely changes in these final moments. However, these scenes do not supply a non sequitur; they reinforce that the sudden appearance of something new within an established framework enriches the whole. Corbet’s thoughtful and intentioned execution of every facet reminds us that bold steps forward are not violations; they are movements toward inevitable change and progress, without which a culture becomes stagnant. Harrison has taken the wrong approach to solidifying his legacy; it’s not about power, brokering deals, accumulating wealth, or commissioning a monument to satisfy one’s ego. When it’s all over, people’s contributions remain, whether they’re artists, immigrants, or both.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review