Gladiator II

By Brian Eggert |

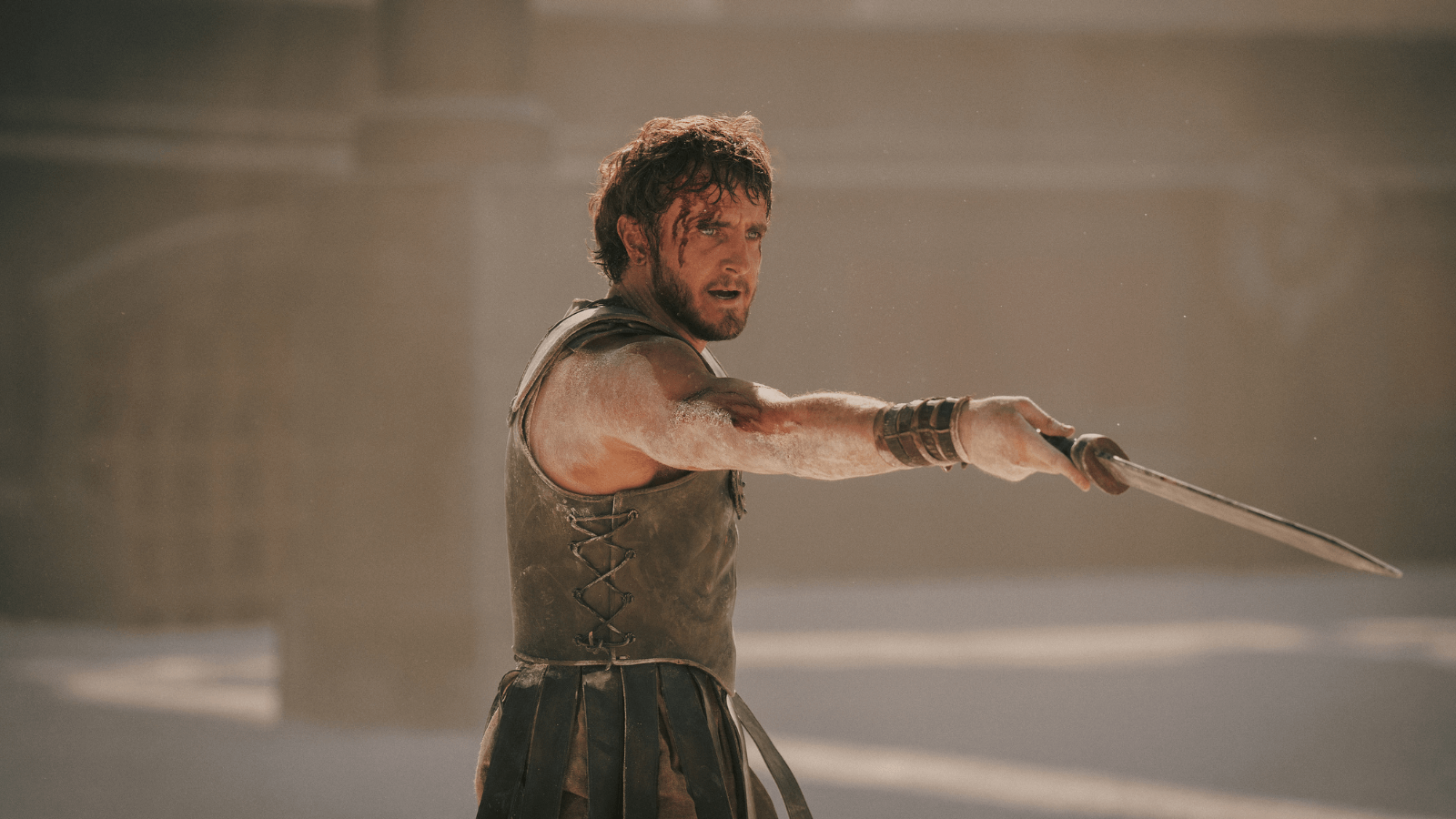

In Gladiator II, Paul Mescal plays a strong, silent type—a warrior poet, a brooding hero. No matter how you describe him, Mescal, star of Aftersun (2022) and All of Us Strangers (2023), inhabits a breed of arena-bound gladiator different from Russell Crowe’s Maximus in Ridley Scott’s 2000 original. Maximus was a career soldier: “The general who became a slave; the slave who became a gladiator; the gladiator who defied an emperor.” Mescal plays Lucius, the grown-up son of Maximus and Connie Nielsen’s Lucilla, who, typical for a legacy sequel, goes through much of the same journey as his illegitimate father. Lucius begins as a soldier, finds himself enslaved and forced into combat to entertain the masses, and ultimately uses his role as a gladiator to usurp the corrupt and decadent figurehead of the Roman Empire. This is a your standard Hollywood sequel, after all, so everything’s predictably copied from its predecessor and amplified to appear more expensive-looking and thematically weightier. This time, our hero has two emperors, twins no less, to unseat. The Colosseum spectacle is bigger and flashier. The performances are broader. Everything moviegoers might want from a sword and sandals epic has been superbly directed by Scott. But, as is usually the case with these things, the sequel’s problems lie in the writing.

David Scarpa, Scott’s screenwriter on All the Money in the World (2017) and Napoleon (2023), spins a yarn that will have historians pulling out their hair and audiences wanting more—but not in a good way. While no one should expect a Hollywood movie to present an accurate history given the inherent poetic license of drama, the writing on this sequel underwhelms. For those who need a refresher, Gladiator ended with Maximus killing Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), the Caesar and duplicitous son of Marcus Aurelius—who had a “dream of Rome” as a nation ruled by the people, not a despot. Maximus’ victory seemed to be the first step in making that happen. For reasons never adequately explained in Gladiator II, Scarpa’s script opens with that optimism dissolved in the time between movies. After Commodus’ death, Lucilla immediately sent away her son, Lucius, who, now an adult, lives in the African coastal town of Numidia and has taken a wife under a false name. When his wife dies in an attack by the Roman navy led by the battle-weary General Acacius (Pedro Pascal), Lucius vows revenge.

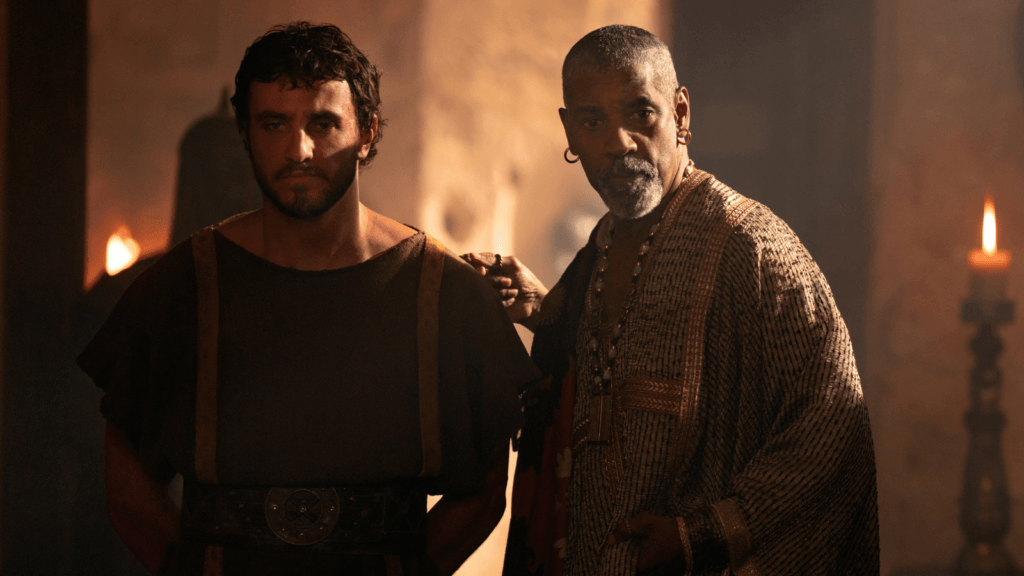

Scarpa’s script establishes the stakes without much concern for character depth. Lucius remains the sensitive soldier, fighting ostensibly the same fight his father did years earlier. Acacius, now married to Lucilla, also occupies that trope. Much like Maximus, Acacius wants a vacation, but his emperors, Geta and Caracalla (Joseph Quinn, Fred Hechinger), want him to conquer Persia and India. The twins behave like gremlins with pale skin, ginger hair, and strung-out eyes from madness and various overindulgences. They feel thinly drawn next to the Freudian head case that was Commodus. Although many of Scarpa’s characters don’t have gradations, his superficial treatment can sometimes mask something more interesting, as with Macrinus—the most compelling role, played by Denzel Washington. A gladiator peddler who was once a Roman slave and now schemes for control, Macrinus takes possession of Lucius and uses his rage and hunger for vengeance in an effort to exploit Rome’s politicians—such as Thraex, a senator with a gambling problem whom Macrinus manipulates. Tim McInnerny plays him in the same grotesque, twitchy mode as his King George IV in Peterloo (2018). But Macrinus isn’t much better than the two lunatics in charge—anyone who wants power that badly has issues. It’s just more entertaining to watch Washington act than Quinn or Hechinger.

Somewhere in the proceedings, and it’s not too difficult to detect where, is an analogy to modern-day America. Historically, the events in Gladiator took place at the end of the Pax Romana (Roman Peace), a period of relative prosperity, stability, and expansion (albeit through imperialism) in the Roman Empire. Gladiator II unfolds after that period has ended, with the empire guided by two power-hungry hedonists. Similarly, the so-called Pax Americana began after World War II, followed by decades of economic growth, military might, and cultural colonization. That time has since ended. Competing economic powers such as China, along with a country-wide existential crisis under the rise of fascistic leaders of the sort we once fought against, have turned America into a mirror image of the failing state of Rome. Scarpa embeds an unsubtle but no less invigorating message that self-interested tyrants—who command bloodthirsty crowds, hanging on every word of these silly-looking madmen who claim to have a connection to the gods—must be removed of their power and replaced by something altogether new while still upholding the interests of the people. The film argues that true leadership is an act of selflessness, less suited for a power monger than a committee with the needs of the people in mind.

Surely, these ideas can be applied to any number of present-day countries run by autocrats. But whatever modern parallels you draw, the trajectory and message bear nagging similarities to the original film. Gladiator also featured a tyrant ruling Rome. Phoenix’s Commodus was hell-bent on ensuring that he was well-liked by the masses to satiate his fragile ego, even if it meant running the empire into the ground. By contrast, the twin emperors in Gladiator II, based on actual figures, feel like cartoons. Though, their line after witnessing a deathmatch, “We are amused,” will no doubt become the meme-worthy equivalent of the original’s “Are you not entertained?” Scarpa prioritizes plot machinations and the demands of a sequel over exploring the psychology of the character. However more sensitive Lucius may seem, he smells dirt like his father, chops off heads like his father, and gives rousing speeches like his father. He even remembers his father in faded moments from the original movie. And the sheer number of remember when moments nodding back to Gladiator, starting with the title sequence in the Scott Free logo animation style, become tiresome.

Washington, as usual, is the most compelling person on the screen, both in terms of his performance and character. While both Lucius and Macrinus have secrets, we know Lucius’ already. We can predict where they will land him. But discovering Macrinus’ past and motivations engages more than any other plot thread. Washington knows how to play a villain—not as a petulant monster like Quinn and Hechinger, but as a man whose reasons we understand and sympathize with. Every line delivery and gesture remind us why Washington is among today’s finest actors. As for everyone else, Mescal’s thoroughly modern screen presence threatens to turn the entire picture into camp, but he sells the role. Lucius may be filled with rage, but he’s also arguably passive, as though everyone else in the story conspires and takes action, while he is pushed and pulled in various directions. So when his fellow gladiators have what might’ve been an inspiring “I am Spartacus” moment, it falls flat because Lucius’ self-involved ambitions prove unexceptional. He’s purely out for revenge and, initially anyway, doesn’t care about building a better Rome. Not avoiding camp is Matt Lucas as the Colosseum announcer, who always seems to be performing with an ironic smile. Or there’s Hechinger, whose character’s syphilitic brain, along with the pet monkey resting on his shoulder in a dress and diaper, feel like overly self-conscious absurdist flourishes. Then again, given the surreal nature of real-life leaders, maybe he’s not so unbelievable.

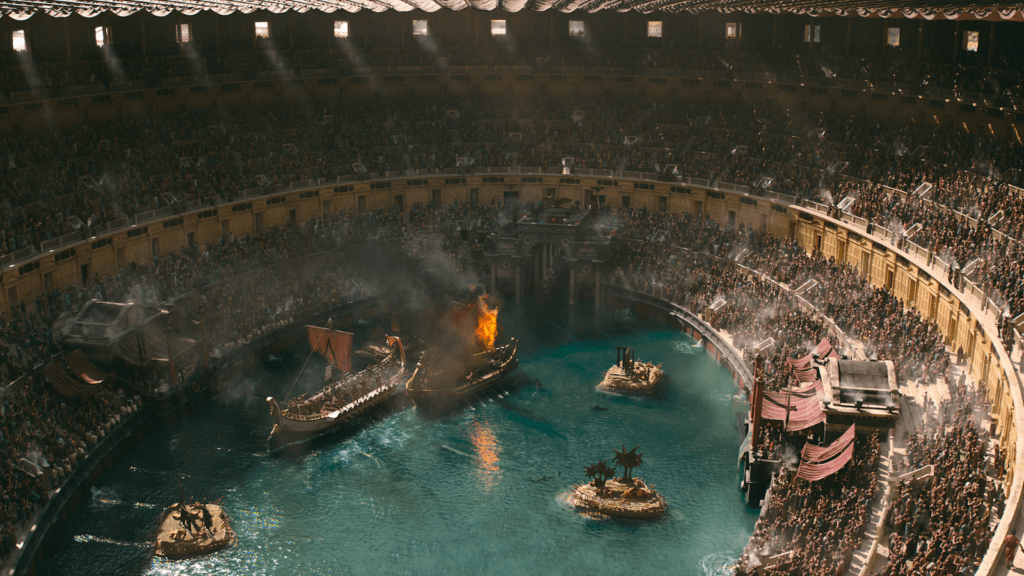

Gladiator II’s case of sequelitis remains treatable given Scott’s unshakable command of such material. No living director better understands movies about costumes, swords, arrows, shields, battlegrounds, dismemberments, ships, catapults, sweeping CGI vistas, and massive crowds and armies. He stages gladiatorial games with care, heightening an already impressive naumachia by adding sharks into the flooded arena for a staged naval battle. Other sequences involve digital mammals, such as baboons and rhinos, reminding us that Romans had little respect for human life but even less for animal life. Spectacle aside, the games feel like relish on the meatier political backdrop, and Lucius’ story becomes the bun that cradles this sausage fest, at once unnecessary but also holding it all together. Elsewhere, Scott and cinematographer John Mathieson, who last worked with the director on 2005’s Kingdom of Heaven, deploy repetitive black-and-white sequences set on the shore of the River Styx, where Lucius hopes to be reunited with his wife and father. These scenes recall the hands-in-the-wheat moments from the original, which, predictably, Scott returns to in a dull callback.

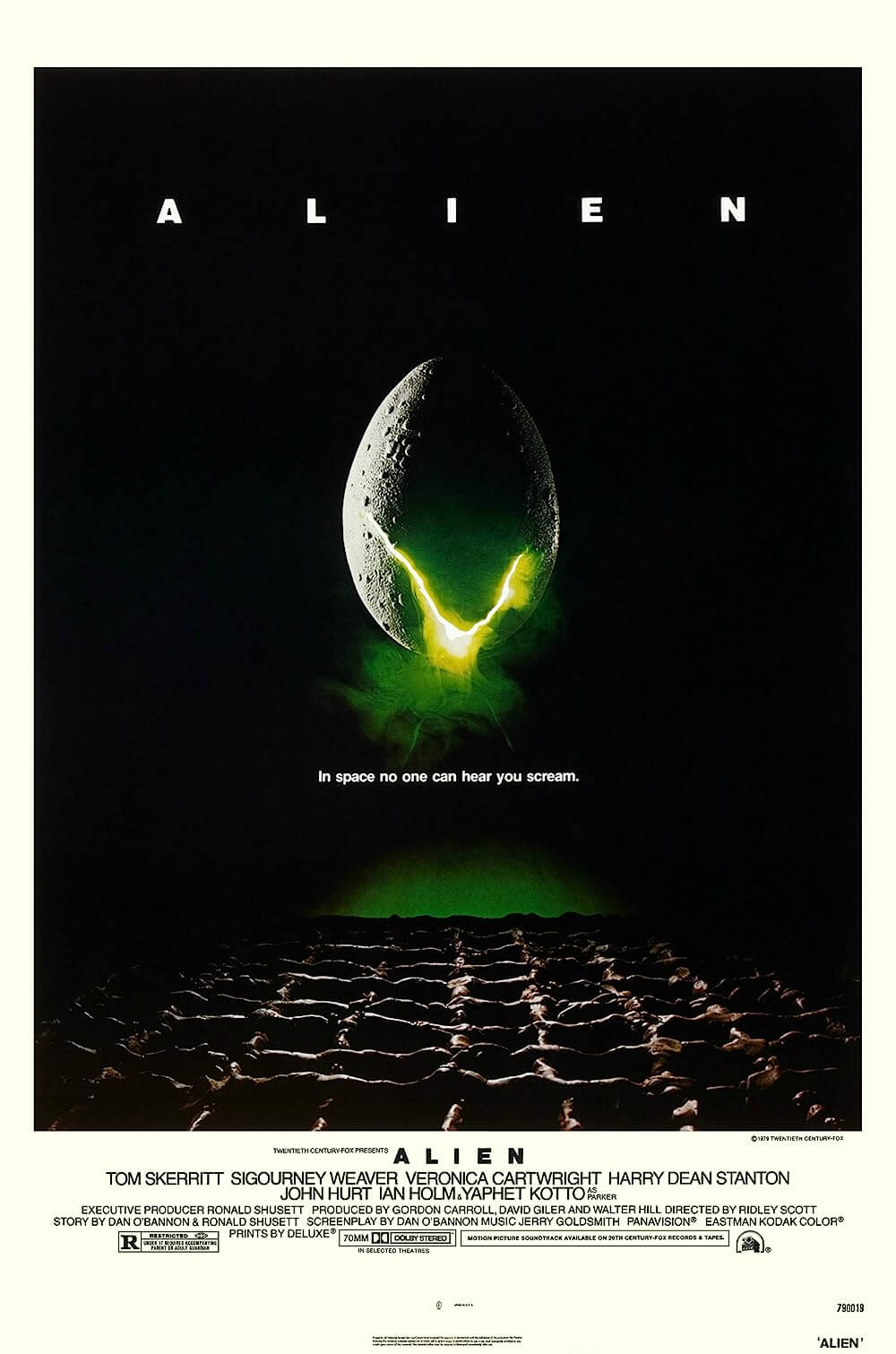

While little about Lucius makes an impression beyond some cursory charms, and the climax is a chaotic sequence with an unfocused solution, Gladiator II is, of course, impressively mounted and directed with the confidence of a master. The cast is in fine form. Harry Gregson-Williams’ score rouses. And the themes prove hopeful, suggesting humanity needs more than panem et circenses (bread and circuses). But watching the film, I didn’t feel like I was witnessing greatness. I remember seeing Gladiator on opening day back in 2000, just a month before I graduated high school. It felt like I was seeing an instant classic, with iconic imagery and dialogue that I would remember for years. Sure enough, that winner of five Oscars, including Best Picture, remains a memorable and rewatchable event. Next to its predecessor, Gladiator II may not be an all-timer or award winner, but it’s easy to get caught up in this 150-minute epic, regardless of its sequelisms and sameness. This is a good movie, not a great one. And that’s a little disappointing.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review