The Definitives

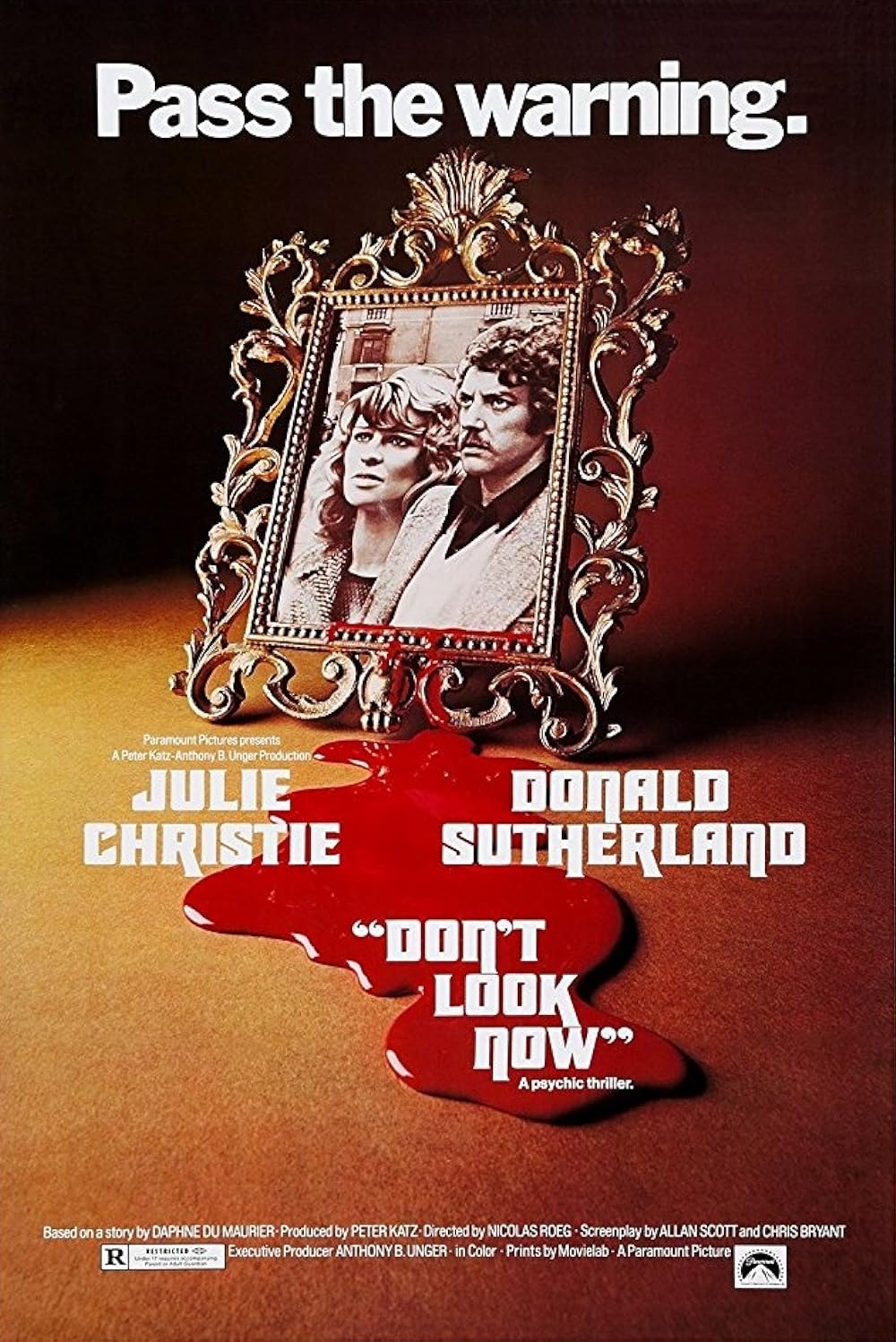

Don’t Look Now

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Nicolas Roeg’s Gothic tale Don’t Look Now writhes with uncertainty, a vagueness that underlines everything revealed to intensify our unease. And yet, this feeling becomes prey to a confident, ingenious style of filmmaking that calculates every move, every cut, to evoke a growing sense of terror. Based on a short story by Daphne Du Maurier, the 1973 film places a moving study of a couple in the throes of grief against the canals and shadowy passageways of Venice, where a series of murders and psychic phenomena establish an unsettling tone. Roeg’s impressionistic style makes leaps in chronology, jumping forward or backward through time in his editing to reinforce an emotion or forewarn of something dreadful to come. His structure follows a symbolic code, employing numerous recurring motifs like scattered pieces to a puzzle, whose picture never becomes whole until the shocking conclusion.

From the opening sequence, it’s evident that Don’t Look Now is about deciphering an inflow of imagery, as though Roeg has tapped directly into our viewing receptors to upload an excess of clues that can only be reconciled and interpreted in hindsight. The story moves forward in a linear way, but then flashes of past and future events burst onto the screen, acting as a sudden, disorienting picture received from the protagonist’s psychic eye. Editor Graeme Clifford said that Roeg, a director who traditionally avoids rehearsal and storyboards, once called the film his “exercise in film grammar,” in which physical film-making becomes the interrelated component that realizes a fairly standard horror story with formative ingenuity. Though Roeg experimented with a similarly allusive editing style on his first two films, Performance (1970) and Walkabout (1971), and later in his career as well, with Don’t Look Now he joins presentation and narrative in a functionalist union.

When compared to its formal staging, the plot is quite simple. In their cottage on the English countryside, John Baxter (Donald Sutherland, sporting a curly wig made by his oft-employed wigmaker) and his wife Laura (Julie Christie) work inside by the fire, while their children enjoy the damp autumn outside. In her red plastic raincoat, daughter Christine plays with her ball near a pond, while inside John studies slides of a Venetian church, one of which shows a red-hooded figure sitting in a pew in the foreground. Christine’s brother Johnny rides his bike over a pane of glass. John spills a glass cup, and some water under the lightbox’s heat melts the slide, making the red-hooded figure appear to bleed. These occurrences would seem like a premonition of what comes next—John instinctively running to the pond to find that Christine has drown—but the viewer might second-guess such a reading by the film’s end. Nevertheless, this opening sequence lays down the emotional and visual themes present throughout the remainder of the film.

When compared to its formal staging, the plot is quite simple. In their cottage on the English countryside, John Baxter (Donald Sutherland, sporting a curly wig made by his oft-employed wigmaker) and his wife Laura (Julie Christie) work inside by the fire, while their children enjoy the damp autumn outside. In her red plastic raincoat, daughter Christine plays with her ball near a pond, while inside John studies slides of a Venetian church, one of which shows a red-hooded figure sitting in a pew in the foreground. Christine’s brother Johnny rides his bike over a pane of glass. John spills a glass cup, and some water under the lightbox’s heat melts the slide, making the red-hooded figure appear to bleed. These occurrences would seem like a premonition of what comes next—John instinctively running to the pond to find that Christine has drown—but the viewer might second-guess such a reading by the film’s end. Nevertheless, this opening sequence lays down the emotional and visual themes present throughout the remainder of the film.

Now in Venice some time later, John oversees the restoration of a church and Laura grows more distant after their loss of Christine, while in the city a murderer is on the loose, leaving bodies in the canals. Dining for lunch one day, Laura happens to meet two English sisters, Heather (Hilary Mason) and Wendy (Clelia Matania). Though blind, Heather has the power of second sight and tells Laura that she saw Christine sitting with her parents during their lunch and that she looked happy. Shaken by the incident, Laura feels her grief could subside if she could only make contact, and with her brief feeling of hope that she and John make love, perhaps for the first time since Christine’s death. That night, wandering through dark walkways to a party, John and Laura are separated, and John sees a small figure in a scarlet Mackintosh hurrying away. Is John seeing things? Was that the same figure from John’s slide? Heather tells her sister, “He has the gift, even if he doesn’t know it, even if he’s resisting it.” Perhaps John saw Christine. To contact their daughter, Laura attends a séance with the sisters, which John thinks is “mumbo-jumbo”, but instead of making contact with Christine, Heather receives a violent vision and warns Laura to leave Venice. John will be in danger if they stay; but he’s obligated to stay and complete the restoration project.

After they receive a call from Johnny’s boarding school reporting a minor accident with their son, Laura leaves for England and John stays behind, promising to take some time off in the near future. At the church, John falls from scaffolding and nearly drops to his death; he determines this is what Heather must have meant by being in danger if he stays. Later, John sees Laura and the sisters on a funeral barge, though he thought Laura was home in England. Growing suspicious, he has the sisters arrested for holding his wife, but realizes he made a mistake when Laura calls him from the boarding school to report that Johnny’s condition is fine. But why did he see Laura on the barge? Apologetically, John returns Heather home from the police station and leaves to rendezvous with Laura, who has just missed him at the sisters’ hotel room. At Heather’s sudden, frantic command, Laura races to find John in the night. He is in danger. Once again, John sees the red-hooded figure and chases after it. He finds the childlike figure standing in a corner, weeping quietly. John says it will be all right, and then the figure turns to reveal a female dwarf, shaking her head as she reaches into her pocket to remove a knife, which she brings down on John’s neck. In the final scene, Laura and the sisters ride a barge to John’s funeral, Laura smiling, lost in some distant memory.

After they receive a call from Johnny’s boarding school reporting a minor accident with their son, Laura leaves for England and John stays behind, promising to take some time off in the near future. At the church, John falls from scaffolding and nearly drops to his death; he determines this is what Heather must have meant by being in danger if he stays. Later, John sees Laura and the sisters on a funeral barge, though he thought Laura was home in England. Growing suspicious, he has the sisters arrested for holding his wife, but realizes he made a mistake when Laura calls him from the boarding school to report that Johnny’s condition is fine. But why did he see Laura on the barge? Apologetically, John returns Heather home from the police station and leaves to rendezvous with Laura, who has just missed him at the sisters’ hotel room. At Heather’s sudden, frantic command, Laura races to find John in the night. He is in danger. Once again, John sees the red-hooded figure and chases after it. He finds the childlike figure standing in a corner, weeping quietly. John says it will be all right, and then the figure turns to reveal a female dwarf, shaking her head as she reaches into her pocket to remove a knife, which she brings down on John’s neck. In the final scene, Laura and the sisters ride a barge to John’s funeral, Laura smiling, lost in some distant memory.

Independently produced with British and Italian funding, Du Maurier’s story was adapted by Alan Scott (Roeg’s collaborator on Castaway (1986), The Witches (1989), and Cold Heaven (1989)) and Chris Bryant. The shoot took place on location in Venice, where Roeg avoided tourist spots to render a sense of isolation and avoid landmark recognition. Few shots contain crowds and even fewer take place on the Grand Canal. While scouting for churches to serve as John’s restoration project, the location manager found the Church of St. Nicholas on the outer edge of Venice, a fortuitous discovery given that within scaffolding was already erected. Christie was eager to work for Roeg, who as a cinematographer lensed her earlier films Fahrenheit 451, Far from the Madding Crowd, and Petulia. She and Roeg attended an actual séance conducted by Leslie Flint, a medium based in Notting Hill, during which Flint, his participants sitting in a circle in the dark, ordered all to “uncross your legs”—a detail so wonderfully suggestive that Roeg incorporated it into the film. The dwarf was played by Adelina Poerio, an unknown whose only film role constitutes one of cinema’s most disturbing, unexpected, nightmare-inducing moments.

However macabre the subject matter and finale, at the film’s center is a beautifully depicted marriage of substance, one further described by the surrounding characters which, classified through their gender, deepen the central relationship. Epitomized by John’s enduring skepticism, the film’s men resist notions of the afterlife, second sight, and religion, hindered by rational minds incapable of wrapping their heads around such abstracts. A detective ponders over the strange occurrences explained to him by John, unable to reconcile what they mean; Bishop Barbarrigo (Massimo Serato) has lost almost all faith, and finds himself in disbelief when confronted with something other-worldly; a school headmaster cannot gather the words to describe an unfortunate accident, and so his wife must take the phone from him. Indeed, the film’s women like Laura and the sisters have open minds toward these spontaneous notions and intuitively understand them, while John remains in denial about his ability. Leaving home for Venice, both John and Laura attempt to heal their wounds, but instead run from their pain, and in doing so propel themselves toward it. And through a series of tragic occurrences, which Laura escapes through her receptivity to psychic phenomena, John falls prey to his cynicism or perhaps some darkly preordained punch line, and becomes consumed by grief.

However macabre the subject matter and finale, at the film’s center is a beautifully depicted marriage of substance, one further described by the surrounding characters which, classified through their gender, deepen the central relationship. Epitomized by John’s enduring skepticism, the film’s men resist notions of the afterlife, second sight, and religion, hindered by rational minds incapable of wrapping their heads around such abstracts. A detective ponders over the strange occurrences explained to him by John, unable to reconcile what they mean; Bishop Barbarrigo (Massimo Serato) has lost almost all faith, and finds himself in disbelief when confronted with something other-worldly; a school headmaster cannot gather the words to describe an unfortunate accident, and so his wife must take the phone from him. Indeed, the film’s women like Laura and the sisters have open minds toward these spontaneous notions and intuitively understand them, while John remains in denial about his ability. Leaving home for Venice, both John and Laura attempt to heal their wounds, but instead run from their pain, and in doing so propel themselves toward it. And through a series of tragic occurrences, which Laura escapes through her receptivity to psychic phenomena, John falls prey to his cynicism or perhaps some darkly preordained punch line, and becomes consumed by grief.

The emotional intensity and realness of John and Laura’s marriage finds lyrical passion in the film’s sole love scene, a sequence in which Roeg intercuts their lovemaking with John and Laura dressing afterward. At once, we see the couple immersed in passion and back to their distanced, but affectionate selves as they dress for an evening out. It is evident there is love between them, but there is also a great deal of pain, and we feel that through every scene. This is in part due to the wonderful performances by the two leads, but more from Roeg’s elegiac approach. Here Roeg’s editing borders on controversial but cleverly avoids overstepping the lines of decency. The long, very naked sex scene caused plenty of hullabaloo among censors upon the film’s release; however, Clifford’s cuts resists dwelling on the gyrations of the couple and, despite the long presence of the film’s stars in the buff, maintains a truth to their nakedness. Although comparably tame by today’s standards, in 1973 the scene fashioned rumors that Sutherland and Christie were actually filmed having sex on set. This assertion was confirmed by Paramount studio head at the time, Peter Bart, who claimed in his book Infamous Players: A Tale of Movies, the Mob, (and Sex) to have witnessed first-hand Sutherland penetrating Christie. Sutherland, Christie, and the producer Peter Katz have all claimed Bart was not on set during the filming of the scene and have since disproved his claim.

Much about what we see onscreen remains unknown within the context of the story as well. Roeg’s presentation, fast yet cerebral cutting, and heavily symbolic imagery keeps us guessing, but also sets us back, making the dark humor all the more upsetting. The experience earns comparisons to one of the best works by Roman Polanski, whose claustrophobic, puzzling, and borderline surreal effort The Tenant (1976) wraps us in a similar mystery of elusive connections and morbid fascinations. So much of this story and its finer details exist to create uncertainty in the viewer, but also accentuate the distance between John and Laura, both emotionally and physically. On the surface, John is American and Laura is British. They leave home for Venice, a city looming with Gothic atmosphere, gargoyles, and decaying architecture; where rats scurry along alley walls and a child’s doll lies forgotten on the water’s edge. All of this further alienates the couple as strangers in a strange land. The séance attempts to bring Laura closer to Christine, but it only creates further distance between she and her husband, as do John’s visions and his refusal to acknowledge their meaning.

Much about what we see onscreen remains unknown within the context of the story as well. Roeg’s presentation, fast yet cerebral cutting, and heavily symbolic imagery keeps us guessing, but also sets us back, making the dark humor all the more upsetting. The experience earns comparisons to one of the best works by Roman Polanski, whose claustrophobic, puzzling, and borderline surreal effort The Tenant (1976) wraps us in a similar mystery of elusive connections and morbid fascinations. So much of this story and its finer details exist to create uncertainty in the viewer, but also accentuate the distance between John and Laura, both emotionally and physically. On the surface, John is American and Laura is British. They leave home for Venice, a city looming with Gothic atmosphere, gargoyles, and decaying architecture; where rats scurry along alley walls and a child’s doll lies forgotten on the water’s edge. All of this further alienates the couple as strangers in a strange land. The séance attempts to bring Laura closer to Christine, but it only creates further distance between she and her husband, as do John’s visions and his refusal to acknowledge their meaning.

The Baxters’ experiences are riddled with the notion of fakery and mistaken identity, as though their surroundings are warning them that their attempts at emotional healing cannot be fulfilled in Venice. Much like he tries to repair his marriage, John works to replace a crumbling mosaic in the church by replacing the tiles with artificial ones. The authenticity of the sisters, too, comes into question. John doubts them and is mistaken for a Peeping Tom when he peers in during their séance with Laura. Early on, when the sisters begin to enter a male restroom only to be stopped by Laura, it almost goes unnoticed; but it should be noted that Du Maurier’s story hints they are “male twins in drag.” At any rate, the sisters are surrounded by peculiarities, and perhaps not what they seem. Of course, the most apparent case of mistaken identity becomes the murderous dwarf, who presents an ostensible “fake” of Christine.

Consumed by the ideas of connectedness and detachment, genuine and fake, Roeg changed details from the book to enhance the viewing experience, to create an undeniable if occasionally indefinable relationship between elements in the story. For example, in the book Christine wore a blue dress and Laura a scarlet Mackintosh coat. Roeg makes an intentional choice and places Christine in a red coat not only to draw John’s attention to her dwarf doppelganger, but also as a warning sign, as if to say ‘Stop, danger!’ to John in his pursuit of the little killer. Red appears everywhere in the film, such as the church John helps restore, St. Nicholas’ church—what saint is more associated with red (not to mention children) than St. Nicholas? Roeg creates these associations, which are present but never over-emphasized with the film, to allow no room for coincidence; in doing so he heightens the sense of psychic paranoia felt by both the Baxters and the audience.

Consumed by the ideas of connectedness and detachment, genuine and fake, Roeg changed details from the book to enhance the viewing experience, to create an undeniable if occasionally indefinable relationship between elements in the story. For example, in the book Christine wore a blue dress and Laura a scarlet Mackintosh coat. Roeg makes an intentional choice and places Christine in a red coat not only to draw John’s attention to her dwarf doppelganger, but also as a warning sign, as if to say ‘Stop, danger!’ to John in his pursuit of the little killer. Red appears everywhere in the film, such as the church John helps restore, St. Nicholas’ church—what saint is more associated with red (not to mention children) than St. Nicholas? Roeg creates these associations, which are present but never over-emphasized with the film, to allow no room for coincidence; in doing so he heightens the sense of psychic paranoia felt by both the Baxters and the audience.

Water—to be more specific, reflectivity—is another reoccurring motif in the story, from the drowning of Christine (in Du Maurier’s story, Christine dies of meningitis) to the many pondering, glittery shots of Venice’s waterways, in which John sees visions of Christine playing. Roeg gives a deep significance to the theme, even more than Du Maurier. The author wrote that the Baxters were vacationing in Venice after Christine’s death, but what parents would escape to a city surrounded by water after their child drowned? Roeg shifts the reasoning to John’s restoration of the church, thus forcing the Baxters into a damp, uncomfortable city in which the wet air leaves them unable to “dry out” after their water-based tragedy. The Baxters want anything but to look at their reflection in the water, or at themselves in the mirror, and face the devastating reality of their loss. Cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond’s camera ponders water flowing down Venice’s canals, where murder victims’ bodies are dredged up, while Roeg connects the image of Christine’s reflection in the pond to the dwarf reflected in the canal, scurrying away from some murder no doubt. Such flowing movement symbolizes the stream of sensory information surging into both John through his undefined psychic ability, and into the viewer through Roeg’s currents of cinematic stimuli.

Falling is another major theme, both in a physical sense and in the sense of falling short, most often associated with John. Just before Christine drowns, John knocks over a glass on his desk, and after, John fails to reach Christine in time and falls in the mud after pulling her body from the lake. John also nearly dies when he falls from scaffolding, and afterward Bishop Barbarrigo tells John his father died in a fall. The Baxters’ son Johnny is injured after an accidental fall. Laura faints in a restaurant, tipping over their table in the process; she also falls short of reaching John after he leaves Heather’s for the final time. Falling, or falling short, bears a connection to John’s rejection of his own psychic abilities. Because he resists his psychic impressions, he fails to secure his footing, both in a figurative and very literal sense. Out of grief, John’s denial takes over and he ignores his intuition. In his deepest, most illogical state of guilt-ridden sorrow, John believes that because he acted on his initial psychic notion in the film’s opening sequence, something terrible happened as a result. If he acts on such a notion again, it could mean something equally disastrous will happen. Perhaps he hopes the dwarf is his daughter, or even the ghost of Christine, and so he rejects the feeling that his daughter could be any danger to him and ignores every unconscious warning sign his ability has flashed before him.

Falling is another major theme, both in a physical sense and in the sense of falling short, most often associated with John. Just before Christine drowns, John knocks over a glass on his desk, and after, John fails to reach Christine in time and falls in the mud after pulling her body from the lake. John also nearly dies when he falls from scaffolding, and afterward Bishop Barbarrigo tells John his father died in a fall. The Baxters’ son Johnny is injured after an accidental fall. Laura faints in a restaurant, tipping over their table in the process; she also falls short of reaching John after he leaves Heather’s for the final time. Falling, or falling short, bears a connection to John’s rejection of his own psychic abilities. Because he resists his psychic impressions, he fails to secure his footing, both in a figurative and very literal sense. Out of grief, John’s denial takes over and he ignores his intuition. In his deepest, most illogical state of guilt-ridden sorrow, John believes that because he acted on his initial psychic notion in the film’s opening sequence, something terrible happened as a result. If he acts on such a notion again, it could mean something equally disastrous will happen. Perhaps he hopes the dwarf is his daughter, or even the ghost of Christine, and so he rejects the feeling that his daughter could be any danger to him and ignores every unconscious warning sign his ability has flashed before him.

Of course, John’s refusal to accept what he sees in his psychic visions leads to his death in a haunting climax. But the more lingering scene remains Julie Christie’s smile in the last shot. As her husband’s casket is carried away at his funeral, Laura stops as if lost in some memory, a creepy yet moving expression appears on her face as she recalls some reminiscence of what? Her husband? Her daughter? One of the many tragic, perhaps now almost humorous, but terrible coincidences that has occurred since Christine died? The film is filled with darkly comic moments for those versed in the story and what happens. Du Maurier’s short story ended with John’s comical last words, “Oh God, what a bloody silly way to die.” Roeg once said he wanted to clap with joy when he read this line, as Du Maurier understood the undeniable correlation between humor and terror, how one emotion can feed from and enhance the other. A similar relationship inhabits the film, as both the characters and the audience want to look and want to look away, and in that exchange the theme of watching and interpreting Don’t Look Now becomes one of cinema’s great films about film. Even the title suggests as much, telling the audience that they should look away, but also warns “don’t look now, but… you should look now for your own sake”—just as we wish we could say to John.

Released on a double bill with The Wicker Man, another picture about a man pursuing a child in red garb with the hopes of helping her, only to be led to his death, Don’t Look Now received positive praise, earned some minor controversy for its frank sex scene, but failed to connect with commercial audiences. As with many of cinema’s most complex works, it requires more than one viewing to fully absorb the film’s formal intricacies and emotional depth, and so only with time have film historians fully appreciated it. In 2011, Time Out London polled “a panel of 150 film industry experts,” including directors Mike Leigh and Wes Anderson to determine the top 100 Best British Films, a list which included masterworks like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), The Third Man (1949), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and Trainspotting (1996). As a British native, several of Roeg’s films received a place on the list, but Don’t Look Now landed the number-one spot. And though film historians and critics are finally giving the film its due praise, considerable ground must be made before the film earns widespread recognition in the public consciousness.

Released on a double bill with The Wicker Man, another picture about a man pursuing a child in red garb with the hopes of helping her, only to be led to his death, Don’t Look Now received positive praise, earned some minor controversy for its frank sex scene, but failed to connect with commercial audiences. As with many of cinema’s most complex works, it requires more than one viewing to fully absorb the film’s formal intricacies and emotional depth, and so only with time have film historians fully appreciated it. In 2011, Time Out London polled “a panel of 150 film industry experts,” including directors Mike Leigh and Wes Anderson to determine the top 100 Best British Films, a list which included masterworks like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), The Third Man (1949), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and Trainspotting (1996). As a British native, several of Roeg’s films received a place on the list, but Don’t Look Now landed the number-one spot. And though film historians and critics are finally giving the film its due praise, considerable ground must be made before the film earns widespread recognition in the public consciousness.

Whether interpreted as a psychic thriller, a Gothic horror story, the blackest of comedies, or an intricate study of grief, Don’t Look Now grows more complex with each viewing until it encompasses each of these qualities at once. After the film’s release, Du Maurier wrote Roeg and congratulated him on capturing the Baxters’ tangled emotional state in another medium; but Roeg’s efforts merit more than congratulation—they deserve celebration. More than any other Roeg film, Don’t Look Now represents an experience that borders on subliminal, its complex emotions rooted so deeply into the arrangement that they become inseparable. This is sophisticated filmmaking beyond the connection of one shot to the next through montage; rather, Roeg uses film itself to induce narrative perception through emotional, temporal, and intellectual transcendence, achieving something truly unique to the artform and unforgettable for the viewer.

Bibliography:

Feineman, Neil. Nicolas Roeg. Boston: Twayne, 1978.

Izod, John. The Films of Nicolas Roeg. Basingstoke: Macmillian, 1992.

Salwolke, Scott. Nicolas Roeg Film by Film. Jefferson, NC: McFarkland, 1993.

Sanderson, Mark . Don’t Look Now. London: BFI (British Film Institute), 1996.

Sinyard, Neil. The Films of Nicolas Roeg. London: Letts, 1991.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review