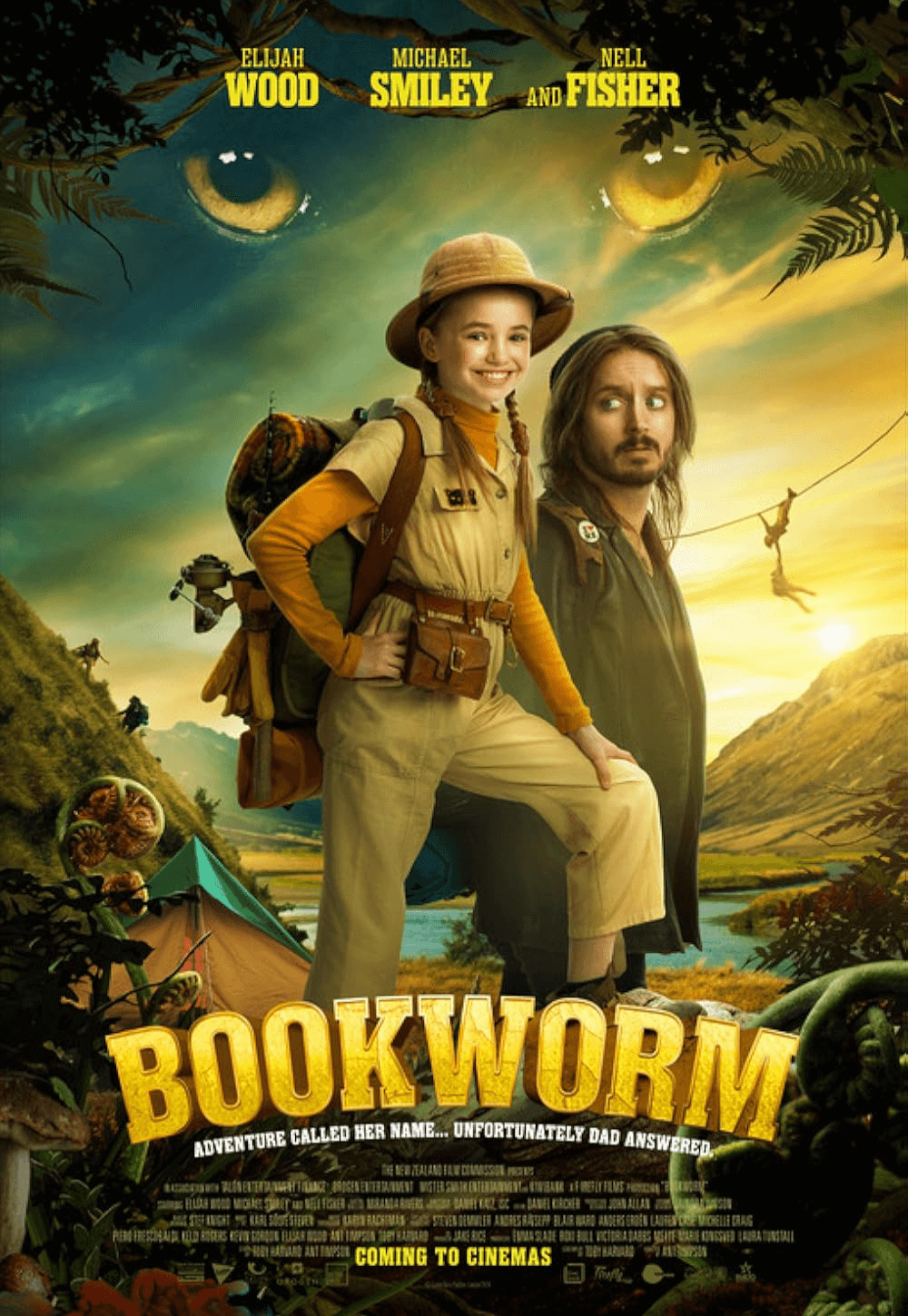

Bookworm

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: This review was originally posted on September 19, 2024. After opening in New Zealand over the summer, Bookworm will arrive in the US courtesy of Vertical Entertainment on Friday, October 18.)

Ant Timpson’s Bookworm is a small revelation. This New Zealand gem offers everything missing from today’s shallow family entertainment: a genuine personality that feels organic, a spectacle that highlights natural beauty over digital artifice, and storytelling that dares to take risks, never playing it too safe. As I sat down to write this review, I struggled to recall the last family-friendly movie that wasn’t a sequel, adaptation, or the big-screen version of a children’s TV show. Even rarer was locating the last family film not overloaded with computer-generated effects, animation, or rigid formulas designed to guarantee blockbuster status. None came to mind. The scarcity of original, straightforward storytelling for families is disheartening. The reason is clear: most studios favor intellectual properties that can be marketed to families, aiming to maximize ticket sales by drawing in everyone, from children to adults. As a result, family films are often populist, engineered to appeal to the broadest possible audience. Yet, Bookworm stands apart, refreshingly free from the usual Hollywood residue.

The screenplay by Toby Harvard, who shares “story by” credit with Timpson, bears some similarity to another story called Bookworm. David Mamet’s original title for the 1997 survival adventure—featuring Anthony Hopkins and Alec Baldwin in the wilderness, hunted by a bear—went by that name before The Edge, directed by New Zealand’s Lee Tamahori. A comparable scenario unfolds here, except it follows a hilariously precocious 11-year-old and walking encyclopedia, Mildred (Nell Fisher), a “card-carrying” bookworm who braves the wild with her estranged father, struggling American “illusionist”—not magician—Strawn Wise (Elijah Wood). They set out to locate and capture evidence of an elusive Canterbury Panther in the area, hoping to secure reward money to help Mildred’s mother (Morgana O’Reilly), who has been in a coma since a freak toaster incident. Mildred has only just met Strawn, an awkward and infantilized sort who wants to be fatherly and needed, but he tries too hard, and they have little in common. When they talk about David Copperfield, they’re talking about very different people. The girl takes one look and sizes him up as a failed magician unsuited for their weekend camping trip. Thoroughly unimpressed, she tells him, “Stick with me; you’ll be fine.” To be sure, on their first night in their tent, Strawn wakes Mildred up and needs reassurance after hearing creepy sounds outside.

Arranged in several chapters, Bookworm doesn’t play like a storybook or escapist lark. The characters develop naturally and with depth, sharing details about themselves that add unexpected layers. Wood is excellent, having worked with Timpson before on 2020’s underseen and underrated Come to Daddy. Although initially an absurd trope, Strawn has a backstory full of failure and humiliation, much of it stemming from his self-sabotaging openness (David Blaine doesn’t help matters, either) that later affects their journey. The character has a heartfelt arc, with Wood showing his capacity for sweetness and subtle comedy. But it’s Fisher who remains central, giving the rare kind of child performance that never feels unnatural or stagey like many young actors. Playing a well-read and intelligent girl, Fisher delivers a dry wit that is a constant source of humor. At one point, Mildred is asked if she would like to live in America. She flatly states that she doesn’t like assault rifles, corn syrup, or high-fives—so the answer is no. She knows literature and the actual meaning of words, and she doesn’t suffer fools, not even her biological father.

Much of Bookworm is about the daddy-daughter camping trip, with Mildred teaching her absent father how to survive in the wilderness, and the two forming their familial bond. They locate the panther, sure, but it’s more about them working through their personal hangups. Mildred is an outsider for her intelligence and inability to make friends; Strawn is too, for more obvious reasons. Both have protective walls to tear down—Strawn with his illusionist’s ego, and Mildred with her intellectual armor. They can be harsh and even mean to one another. Because she is so smart, Mildred’s remarks can cut deep. “You’ve failed as a man and crapped the bed as a protector,” she tells him at one point, leaving Strawn eviscerated. Yet, they have a reciprocal relationship; they each offer and need the other for support. These shaky bonds come into question when Bookworm takes an unexpected turn. Two fellow hikers dressed in orange plaid (Michael Smiley and Vanessa Stacey), the former a heart surgeon with a black belt and the latter a devoted fan of American soap operas, introduce an unexpected element that escalates the weekend from a panther scouting trip to a survivalist adventure.

Shot on the Canterbury Plains in the southern region of New Zealand, the film looks gorgeous and often quite dangerous. Timpson reteams with his Come to Daddy cinematographer Daniel Katz to capture the landscape in rich scenes showcasing the country’s natural splendor. Even though the production relies on a not-altogether-convincing CGI panther for a few brief scenes and a couple of zippy drone shots, much of the film registers as an old-school adventure. Even the music, composed by Karl Sölve Steven, rings of Ennio Morricone with a folksy, outdoorsy quality that feels epic-sized yet intimate. And despite the film’s talk of adventure—“Chapter 4: The Spirit of Adventure”—Bookworm doesn’t resort to the typically overblown third act of Hollywood fare. The modest conclusion shows Timpson and company are more concerned for the characters and their journey than supplying a broad spectacle catered to the average moviegoers’ sensibilities.

Without feeling derivative, Bookworm made me think of entertainment from the 1980s that tested what it meant to be “for kids”—stuff like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Gremlins (1984), The Neverending Story (1984), The Goonies (1985), and Return to Oz (1985). Studios used to take risks and trusted their audiences more than today, allowing their movies to be a little strange, weirdly specific, and press the limits of their PG rating. Offbeat favorites from this time show how kids become wiser from their mild distress and trauma after feeling scared or tense in a movie environment. By pushing the boundaries of conventional family entertainment, they encourage creative and critical thinking, forcing children to use their imagination rather than spoon-feeding them another helping of safe products. Today, these titles have been reference points for a generation of filmmakers who grew up watching them. But more often than not, the result pays homage or simply regurgitates popular themes, evidenced in The Mitchells vs. The Machines (2021), Netflix’s Stranger Things series, and countless other examples.

Although Timpson’s film isn’t likely to leave children scarred from the experience, it does not pander to families. An unpredictable quality inhabits the proceedings, both in terms of what the characters are capable of and what happens to them. Between the panther, the interlopers, a daring rope feat worthy of Cliffhanger (1993), and a brief psychedelic interlude, Bookworm has elements of a classical family adventure, albeit with a hint of strangeness that keeps the viewer destabilized. However, the distinctive humor that registers as characteristically Kiwi defies expectations, and much of what occurs does not conform to the typical blockbuster mold. The closest comparison might be another New Zealand adventure involving a wayward child and unlikely father, Taika Waititi’s Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016). Like that film, the earnest relationships remain central to Bookworm, augmented by Wood and Fisher’s onscreen chemistry. They make everything happening onscreen, even when it’s somewhat standard adventure material, all the more compelling.

(Editor’s note: An earlier version of this review co-credited Karyn Rachtman as the composer; however, she is the music supervisor.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review