The Substance

By Brian Eggert |

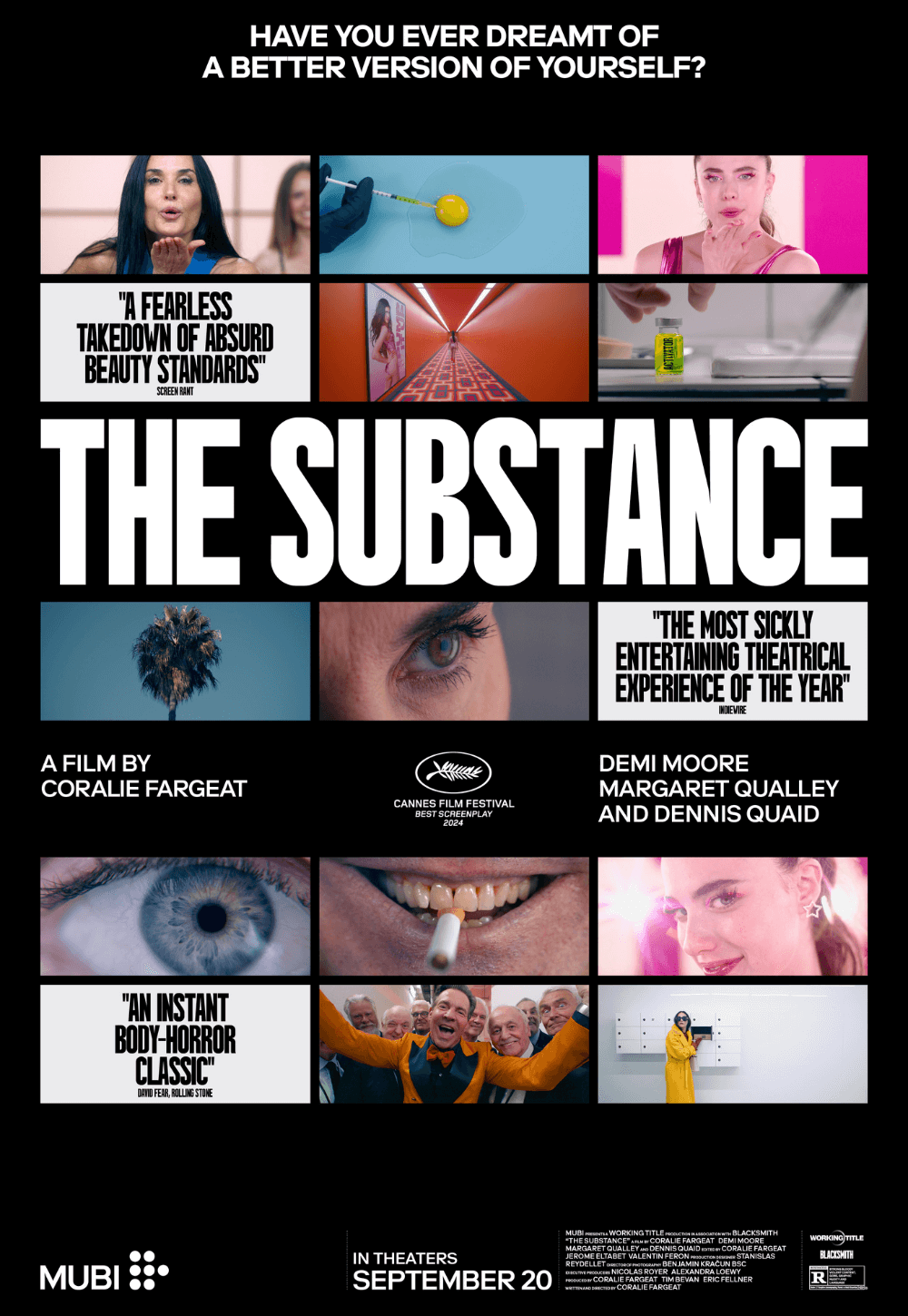

Strict rules mandate the mysterious yellow-glowing liquid at the center of The Substance, Coralie Fargeat’s simplistic but visually audacious takedown of beauty standards through the lens of satirically over-the-top body horror. Users may only activate the titular product once to “unlock” their DNA, prompting a younger double to emerge from a gaping wound on the user’s back. The new and improved version goes out to play as the original sleeps, but they must inject a stabilizer every day afterward or face debilitating side effects. After seven days, the younger version tags out, giving the original a week to live, and vice versa after a week, with no exceptions in the routine. “Remember You Are One,” the rules state. Fargeat flashes these rules onscreen and embeds them in the voiceover with persistent reminders, beating the idea to death so we anticipate what will happen when they’re broken. There’s a lot of overemphasis in The Substance. This film seeks to critique how the media and entertainment industry set impossible physical ideals. Its methods of criticism are broad and bloody but don’t have much to say beyond its stated purpose, which it reiterates to no end. Fargeat hasn’t made a film of memorable characters or thoughtful lessons to counteract her superficial target. Instead, she has made a film of vivid cinematic imagery that, rather than subverting the absurd expectations placed on women about their appearance, reinforces the standards it hopes to censure.

Much has been made of the writer-director’s sophomore effort since its debut at the Cannes Film Festival this year, where, bafflingly, Fargeat won the Best Screenplay award. Drawing inspiration from The Picture of Dorian Gray and other stories warning against vanity, the film follows Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a Hollywood icon whose Walk of Fame star is an obvious metaphor for her relentless pursuit of youth and attention. The sidewalk star is visited at the beginning and end of the film, showing how it deteriorates and is abused over time—a heavy-handed emblem for her relentless pursuit of fame, despite undergoing no end of punishment to achieve it. When her outlandish producer—played by Dennis Quaid, who was only more animated in Great Balls of Fire! (1989)—announces he will replace her on her throwback exercise show, “Sparkle Your Life,” she turns to The Substance to reclaim her youth. Once she injects herself with the solution, which looks like radioactive Mountain Dew, Sue (Margaret Qualley), a “better” version of her, oozes out of her back. Before long, Sue heads to an audition for a new career as a workout show starlet on TV, while Elisabeth remains on the bathroom floor for a week, fed on goop from a series of tubes, waiting for the transfusion that will allow them to switch places.

The instructions say the two must alternate on a strict 7-day cycle, and while active, Sue maintains her composure with regular injections of Elisabeth’s spinal fluid. Although the rules remind them “You Are One” and to “respect the balance,” Elisabeth and Sue do not share the same mind or thoughts nor show concern or affection for one another. Fargeat remarks on how a person’s younger self may seem like a different person, if not wholly unrecognizable after you’ve lived a few decades. But almost immediately, Sue develops a greedy streak and discovers that she can stay out longer if she extends the permitted week-long window. Granted, this leaves Elisabeth to wither and wrinkle. Rather than stop the process, however, Elisabeth acts out with manic cooking and binging—scenes filmed as though Fargeat couldn’t imagine a more disgusting sight than overeating. Sue becomes fed up, and her eventual abuse of the timeline leaves Elisabeth resembling one of the unmasked hags from Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches (1990). This leads to a vicious, petty, and escalating competition between the two, culminating when their mutual abuses result in a malformed, slimy creature (think Brian Yuzna’s 1989 splatterfest, Society) that’s proclaimed a monster and douses its audience in streams of blood, pleading with tragic desperation, “I’m the same!”

In 1966, John Frankenheimer released a film called Seconds, starring John Randolph as a dissatisfied banker in his fifties who undergoes a radical procedure to surgically alter himself and start a new life. After leaving his family and going under the knife, he emerges as Rock Hudson and adopts a new identity. But no matter how youthful he appears or how liberated he feels, there’s something rotten inside him that cannot be fixed with a superficial change. Now, imagine that film, except directed by Stuart Gordon of Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986) infamy, and you might get a sense of Fargeat’s approach to The Substance. But the French director also nods to David Cronenberg, Stanley Kubrick, Andrzej Żuławski, Terry Gilliam, David Lynch, and Quentin Tarantino in her film. When Raffertie’s score samples Bernard Herrmann’s eerie theme from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), the moment nods to their shared themes of men shaping women, but the transparency of this choice neutralizes its meaning. The whole stylistic approach feels pieced together from other influences, making the result seem less like the work of an original voice and more like greatest hits filmmaking. Take a scene when Elisabeth has a breakdown in the mirror before a date, slathering makeup around her face in a manic outburst. This might be a raw emotional moment; instead, it feels like a reference to Diane Ladd smearing lipstick in Wild at Heart (1990).

Fargeat’s allusionism, compounded by her inability to disguise her cinematic influences, might be less unbalanced if her film had more to say or gave us reasons to care—such as, say, dimensional characters. Unfortunately, there’s not much here beyond her message about men demanding that women look a certain way, that they should “always smile,” and how that translates to women developing complexes, disorders, and bodily self-hatred. One of Fargeat’s more inspired flourishes is casting Moore, a celebrity whose body paradigm shifts have prompted the media’s conspicuous and invasive commentary, particularly in the 1990s. Moore puts much of herself into the role, no doubt channeling her extratextual experiences with how the industry has reacted to her physical appearance over the years. It’s all the more absurd that Elisabeth’s industry has shunned her because Moore, at 61, never looks like a washed-up performer. Let’s credit Moore’s casting to Fargeat saying that, even when someone still looks good, Hollywood often prefers them younger. Qualley and Quaid also supply solid performances, but Fargeat’s script allows for only broad one-note types that register less as people than roles in a grotesque comedy sketch about body dysmorphia. Fargeat doesn’t even bother writing supporting parts—not one friend, family member, or even an assistant who might help reveal some inner dimension to her characters.

Although the filmmaker draws from a thematic well that has supplied films from All About Eve (1950) to Mulholland Drive (2001), her treatment of characters and dialogue has none of the same intrigue or personality as its antecedents. And because The Substance is the kind of film where, once you notice one underdeveloped aspect, others reveal their inadequacy too, it’s difficult to care much about anything happening. This stems from the lack of specificity in Fargeat’s script, which sidesteps her characters and basic plot details. Take the unnamed company that contacts Elisabeth. She needs only to dial a number printed on a USB drive, and this miracle drug is delivered to a locker, waiting for her. There’s no mention of what Elisabeth pays for the treatment, if anything, so how does this organization make money? Other films have dealt with these questions better to suspend disbelief. Death Becomes Her (1992) and Seconds offered vague but satisfying enough solutions to the financial question, but Fargeat does not even provide a cursory explanation. Doubtless, she feels no need to craft a believable world while operating in such broad satire-horror terms, but the effect left this critic at a frustrating distance.

Fargeat’s obsession with surfaces—not just bodies but also elaborate sets, complete with her inclusion of a hallway and restroom inspired by The Shining (1980)—leaves most of the characters overshadowed by the film’s overblown style. Cinematographer Benjamin Kracun’s wide-angle lenses, handheld cameras, and frequent shots employing Kubrickian symmetry make the viewer unavoidably aware of every visual flourish to the point of distraction. When Elisabeth first injects herself, she experiences trippy color flashes reminiscent of the extended, psychedelic “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Both Elisabeth and Sue also have nightmares about organs bursting from their back or a chicken leg hiding under the skin. And Fargeat shoots rear ends with as much fetishism as Tarantino does feet, using low angles with, one assumes, ironic intent. The finale comes to life with some convincing make-up effects, bringing a warped monstrosity to life with gleefully disgusting detail and a twinge of sadness. Still, the filmmaker’s surface-level treatment of her story cannot help but feed pop culture’s shallow interests and bodily preoccupations.

The Substance might have delivered a more effective satire if Fargeat hadn’t spent so much time ogling Qualley with her camera during extended workout sequences or repetitive, self-admiring scenes in the mirror. The director takes a similar approach to how she filmed the protagonist in Revenge, her 2018 rape-revenge debut. The camera glides over her subject’s body in protracted shots that attempt to shove the male gaze in our faces with ironic intent. But repurposing and recontextualizing this imagery, even with a flippant technique to emphasize its ludicrousness, doesn’t result in a successful critique—at least, not based on the audible “Yummy” from one male moviegoer in my screening. Fargeat’s approach risks viewers not getting the point with The Substance, which, of course, remains out of her control. In her attempt to entrap her audience in the omnipresent male gaze to the point of exaggeration and therein critique it, she spends more time appreciating Qualley’s beauty than questioning how the entertainment industry exploits women. Much as she did in Revenge, Fargeat embraces the cinematic tradition of exploiting women’s bodies, even as she tells a story intent on making us question the degree to which the male gaze affects female performers.

Devoid of subtext, complex characters, and leaving nothing for viewers to uncover, The Substance doesn’t have much to offer once you set aside the potency of its arch imagery and presentation. In its two-hour-and-twenty-minute runtime, the film spends far too much time repeating the same phrases, the same visuals, and reiterating the same points. The film is stylistically broad to the degree of sacrificing any investment in the characters, and because no one onscreen has much depth, the material becomes comical instead of frightening or insightful. The treatment plays better as a black-as-pitch comic parable, with its archetypal characters representing ideas more than having relatable traits, to the extent that the whole concept might’ve been better served as an hour-long episode of Tales from the Crypt. Fargeat’s focus on aesthetics might be dismissable, except her film represents a missed opportunity. With the “heroin chic” look from the ‘90s coming back in fashion and miracle weight loss drugs saturating the market, The Substance has the potential to condemn beauty standards and investigate their consequences with some insight. But this is the cinematic equivalent of throwing acid at the Mona Lisa: unproductive.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review