The Debt

By Brian Eggert |

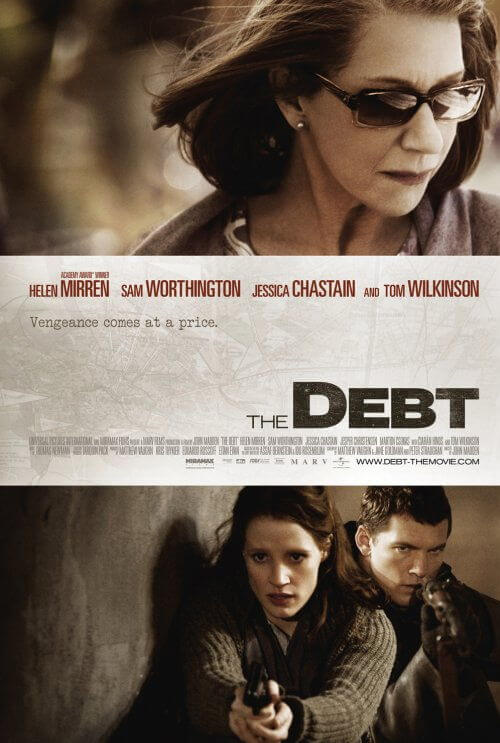

A mismanaged structure hinders The Debt from being the effective spy thriller it could be. Employing a nonlinear plot that leaps back and forth between past and present, the film by director John Madden (Shakespeare in Love) concerns three agents of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, who, in 1966, track down a Nazi war criminal in East Berlin. Scenes in the past are framed by “modern day” events in 1997 when a book has been written about their important mission. Reflecting on the past, the now matured Mossad agents recall the actual events, their memories deviating from the unreliable narration of the book. Far too early in this process, a twist unveils a secret that should have been the film’s climax. But after the secret is revealed, the film goes on for much too long and fails to have the same impact.

Based on the 2007 Israeli film Ha-Hov, the script was adapted by three writers (Matthew Vaughn, Jane Goldman, and Peter Straughan) to have the stripped-down narrative form of a John Le Carre spy novel. Yet, there’s also a melodramatic tone and importance behind the performances and dialogue that recall Steven Spielberg’s similarly themed release, Munich. The film opens in 1966 when David (Sam Worthington), Rachel (Jessica Chastain), and Stefan (Marton Csokas) return home to Israel for a hero’s welcome. They have reported back from a successful mission, having found and killed the infamous Surgeon of Birkenau, Dieter Vogel (Jesper Christensen). Rachel’s face bears a horrible gash; she was assaulted by Vogel after his capture. When he attempted to flee, Rachel shot him. At least, this is what was written in a new publication by Rachel’s daughter in 1997, but through their grave glances at one another, the three characters David (now Ciaran Hinds), Rachel (now Helen Mirren), and Stefan (now Tom Wilkinson) suggest the book contains falsities.

From here, the film leaps into the past for an extended time—almost the entire body of the story in fact—and shows us how the three Mossad agents found Vogel and plotted their mission to kidnap their target and return him to Israel, where he was to be placed on trial. Under an assumed name, Rachel meets with a gynecologist, Doktor Bernhardt, who is believed to be Vogel in hiding. An intense, suspenseful scene progresses as Rachel, her legs in stirrups, becomes totally vulnerable to this evil man. After he is taken during their botched scheme to sneak him out of East Berlin, he remains their prisoner in an enclosed apartment. Each agent takes shifts watching this monster and feeding him, as he toys with them one by one, exposing their vulnerabilities and insecurities. Though not quite as deliciously despicable as Christoph Waltz’s Nazi in Inglourious Basterds, Christensen is very effective in his few scenes.

Meanwhile, all but trapped in their secret hideout with a Nazi as their superiors determine a way to get Vogel out of the country, a love triangle emerges between the three agents and grows more complex with Rachel’s unexpected pregnancy. Here enters the melodramatic element that lingers for the remainder of their lives, realized in strong performances all around, particularly Chastain, who has had an incredible breakout year after The Tree of Life and The Help. Csokas fills his role as the hostile and two-dimensional leader well, whereas Worthington (Avatar) struggles to hide his Australian accent under his clumsy Jewish one. The present-day versions were cast more for the actors’ notoriety than for looking like their younger counterparts. Hinds and Wilkinson feel underused, and Mirren is exceptional, as usual. Given the incredible makeup effects used to make Christensen look thirty years older, one wonders why the filmmakers didn’t simply put their young actors in the makeup chair for a more believable transition.

Completed in mid-2010, Miramax was set to distribute The Debt over the 2010 holiday season, before which it was discussed as a major Oscar contender. But the studio went belly up and sold its inventory, and the film collected dust for several months until Focus Features released it as a late summer farewell from superheroes and sci-fi blockbusters. Given the cast, setting, and heavy themes involved, one could hardly be blamed for expecting more. The frustrating part is, somewhere within this footage exists a very good, if not great, movie. But it never finds a purpose to its nonlinear structure in the way that something like The English Patient does, which is to say, this story would no doubt have the same meaning if told in linear form. As a result, the film never makes a crucial connection beyond basic plot-driven intrigue, as Madden and his editor Alexander Berner simply failed to piece it together in an emotionally satisfying way. Audiences drawn by its cast will feel contented, if not mildly disappointed, by the outcome, no matter how watchable it proves to be.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review