Reader's Choice

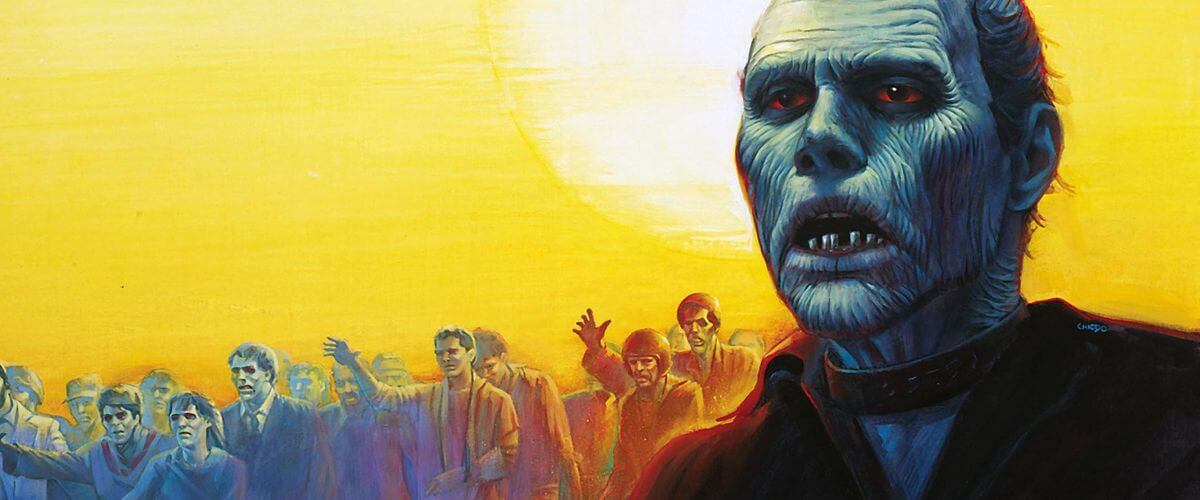

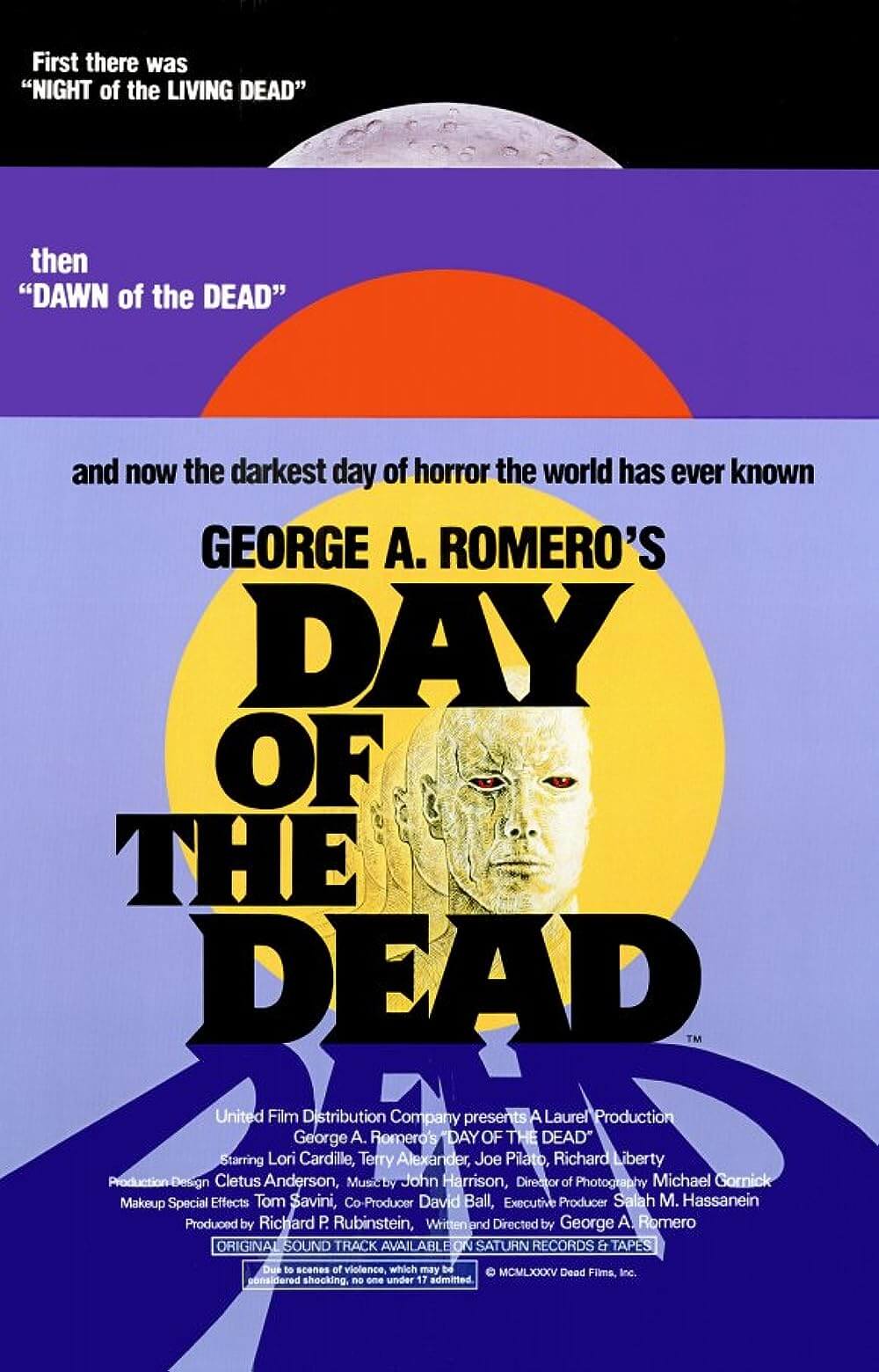

Day of the Dead

By Brian Eggert |

George A. Romero’s Day of the Dead is about breakdowns in civility—the manners, relationships, and logic that buttress our culture. Many of the film’s characters return to regressed versions of themselves in the zombie apocalypse, unleashed from the expectations of their culture. In his book The Civilizing Process, Sociologist Norbert Elias argues that Western culture developed out of people’s “increased emotional control, a greater restraint of their spontaneous feeling.” Notions of self-repression created social norms and so-called civility, which became synonymous with the contemporary definition of civilized culture. Many of the film’s characters are completely unhinged and out of control, leading to the decline of institutions. Romero himself described the film’s subject as the “disintegration” of “trust in institutions,” which flawed individuals always control. A reflection of the Reagan-era culture war, the film depicts the fragility of civilization through the lens of the military and scientific communities clashing with one another. To be sure, though it is a zombie film, and further, one of the most sublimely gory spectacles of the 1980s, it’s also teeming with ideas and cynicism about humanity’s supposed progress—perhaps more than its contemporary audience was willing to tackle. Day of the Dead is a great work of horror; however, it takes days, sometimes weeks, or even years after viewing the picture to finally process how deeply its bleak message penetrates.

When it was released in 1985, the characters’ psychological and physical strain and the story’s bleakness confronted critics and audiences alike. Roger Ebert observed, “The characters shout their lines from beginning to end, their temples pound with anger […] until we are so busy listening to their endless dialogue that we lose interest in the movie they occupy.” Variety described characters as “unintentionally risible,” ignoring that Romero’s earlier uses of the zombie included social satire. Beyond the bad reviews, the film was distributed with an underwhelming marketing campaign, without an MPAA rating, and limited circulation by United Film Distribution Company (UFDC). Audiences were further confused by The Return of the Living Dead, an unrelated and comparatively more comical take on Romero that debuted a month after Day of the Dead hit theaters. Even though Romero’s film made a sizable profit, it was considered a failure among critics and the original audience. And these factors combined into a general miasma over the film until cult worship and critical reappraisal struck in the subsequent decades.

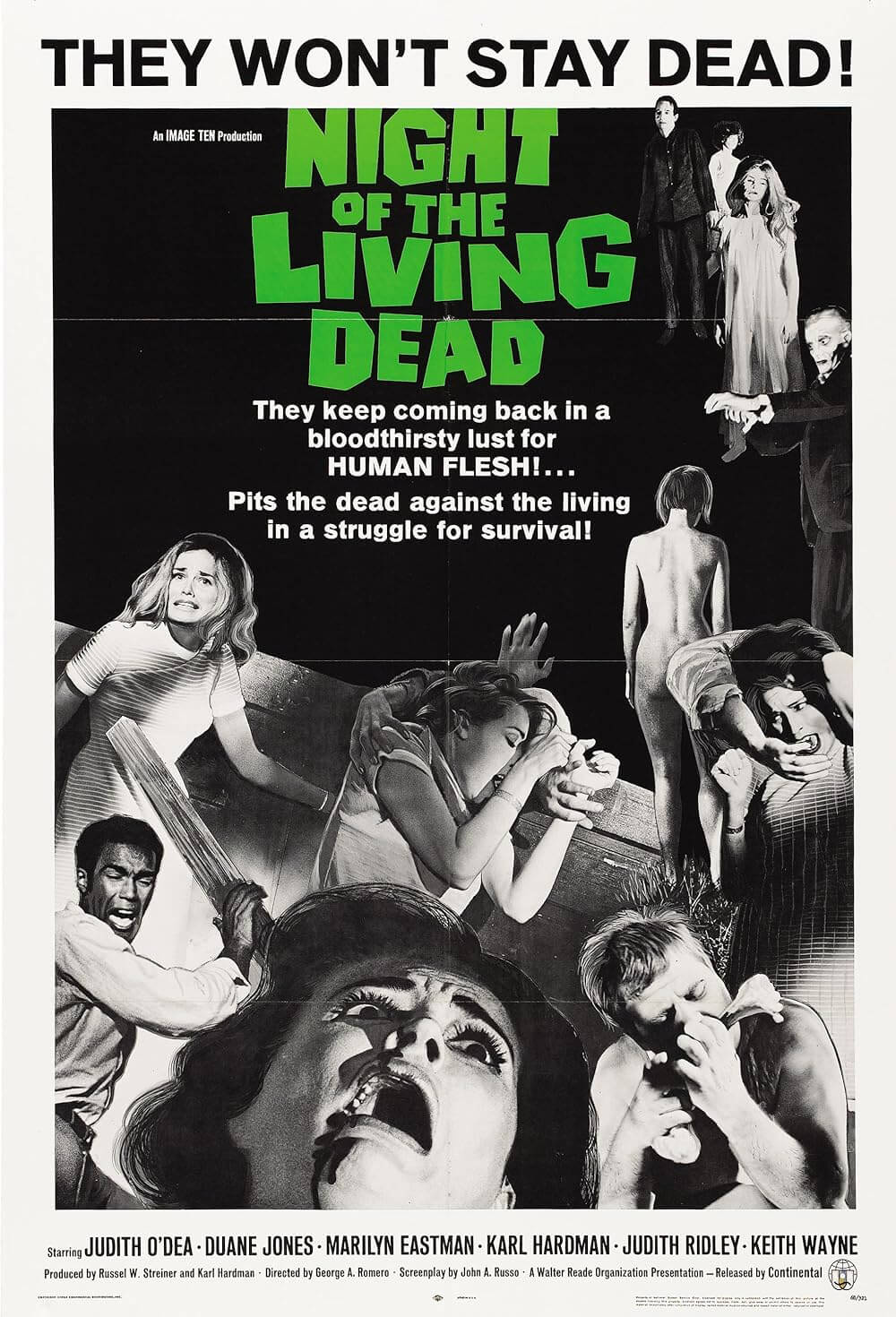

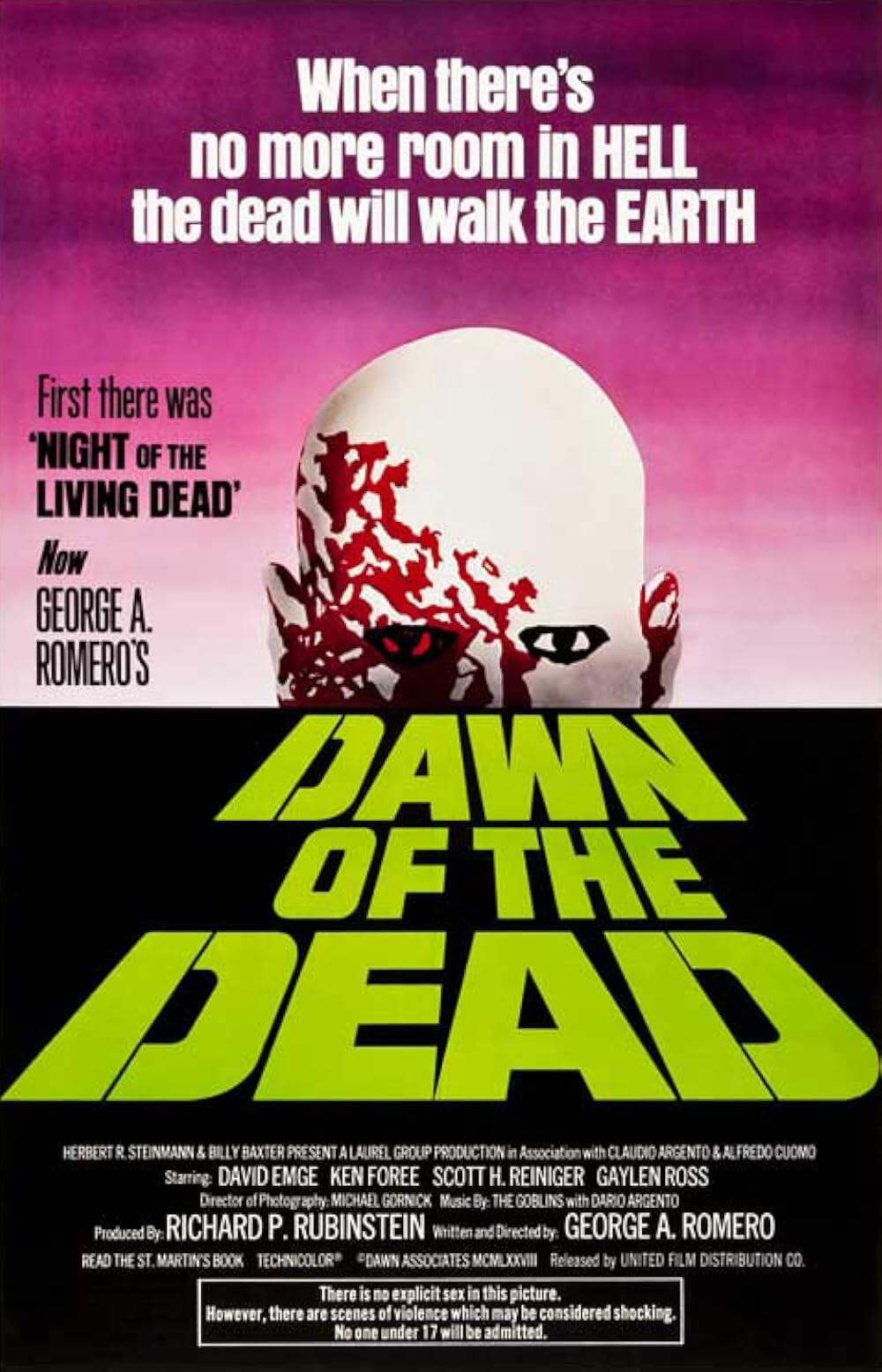

Admittedly, it’s difficult to watch a film where everyone is either close to or well beyond the breaking point. As a result, viewing Day of the Dead is an uneasy experience, like spending 100 minutes in a lunatic asylum. And some aspects of the production prove low-grade or just grating: an electronic music score by John Harrison better suits a Caribbean resort ad from the 1980s; the characters are generally unpleasant; and the aggressive acting can distract from the viewer’s enjoyment during their first screening. Finally, of course, inevitable comparisons to the viscerally emotional, intellectual, and satirical experiences of Romero’s previous zombie shockers, Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978), leave Day of the Dead overshadowed. But over the years, despite these complaints, one comes to appreciate Romero’s severe observations in his third zombie film as the most desolate he explored.

Admittedly, it’s difficult to watch a film where everyone is either close to or well beyond the breaking point. As a result, viewing Day of the Dead is an uneasy experience, like spending 100 minutes in a lunatic asylum. And some aspects of the production prove low-grade or just grating: an electronic music score by John Harrison better suits a Caribbean resort ad from the 1980s; the characters are generally unpleasant; and the aggressive acting can distract from the viewer’s enjoyment during their first screening. Finally, of course, inevitable comparisons to the viscerally emotional, intellectual, and satirical experiences of Romero’s previous zombie shockers, Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978), leave Day of the Dead overshadowed. But over the years, despite these complaints, one comes to appreciate Romero’s severe observations in his third zombie film as the most desolate he explored.

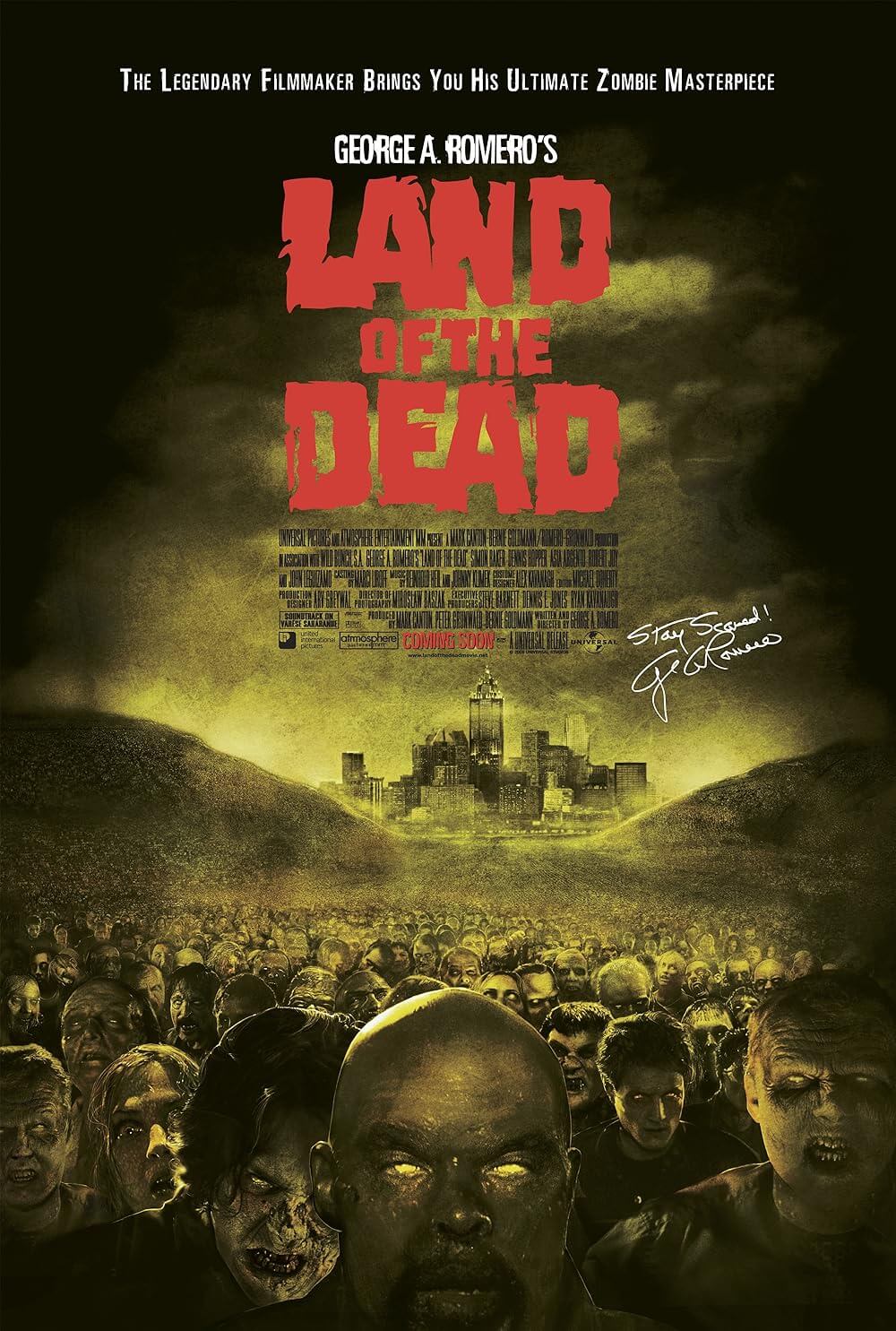

The film was the final obligation of a three-picture deal Romero signed with UFDC, stipulating that one of them would be a sequel to Dawn of the Dead, a hugely successful picture at the worldwide box office. Romero made Knightriders (1981) and Creepshow (1982) under the deal, and finally Day of the Dead. His original concept was a sweeping script that resembled what would later become Land of the Dead (2005), complete with society rebuilding itself on an island haven in Florida. Unfortunately, budgetary constraints required massive rescaling of Romero’s initial script, and he shot the revised draft for just over $3 million. Aside from a few exteriors, much of Day of the Dead was filmed in a limestone mine, a vast storage depot near Romero’s usual stomping grounds in Pennsylvania. The film’s inescapable underground quality is apparent from the first scene: A woman named Sarah (Lori Cardille) huddles on the floor in a concrete room with nothing but a calendar and her nightmares. She regards the calendar for a moment before zombified hands break through concrete bricks in a sudden outward thrust—a shocker and arguably the single most jump-inducing image in Romero’s career.

Day of the Dead unfolds in an underground military bunker and missile silo. The zombie apocalypse has long since eaten away at the human race topside. Twelve survivors comprised of military personnel and civilian scientists research a solution to a situation that has already consumed civilization. They’ve lost radio communications with other bunkers; surveying nearby cities by helicopter, they find no other survivors. It’s apparent within the first scenes that the remaining few in their group slowly deteriorate, especially the soldiers. Everyone’s desperate for hope, but there’s none to be had. What possible solution could there be when Logan (Richard Liberty)—the resident mad scientist dubbed “Frankenstein” by the others—estimates that there are four-hundred thousand undead for every human? Nevertheless, the research continues, which requires zombie specimens and calls for the military men to corral and ostensibly hogtie Subjects of the Living Dead, risking their lives in the process. But what is Logan doing with his experiments in his lab? What solution is he working toward?

Romero’s screenplay draws the lines between the bunker’s three groups: the military, led by the despotic Capt. Rhodes (Joe Pilato); the scientists, given humanist sympathy by Sarah; and two separatists, Jamaican pilot John (Terry Alexander) and Irish handyman McDermott (Jarlath Conroy), who want nothing to do with either establishment. At the outset, Rhodes declares martial law and wants results no matter how unsuitable the conditions. Meanwhile, his men are exhausted, overworked, and going mad. The grunts, Rickles (Ralph Marrero) and Steel (G. Howard Klar), leer at Sarah and make perverse jokes, cackling in maniacal, crazed laughter that reveals their constant state of terror. These performances recall the weasels from Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1985), whose laughter will get them killed. The separatists wish they were on a beach somewhere, soaking up sunshine for the rest of their days. But most of the film follows Sarah, who finds herself struggling to find some common ground between them all, some civility they can all adhere to, except there’s none left. “What you’re doing is a waste of time,” John tells her. “And time is running out.”

Romero’s screenplay draws the lines between the bunker’s three groups: the military, led by the despotic Capt. Rhodes (Joe Pilato); the scientists, given humanist sympathy by Sarah; and two separatists, Jamaican pilot John (Terry Alexander) and Irish handyman McDermott (Jarlath Conroy), who want nothing to do with either establishment. At the outset, Rhodes declares martial law and wants results no matter how unsuitable the conditions. Meanwhile, his men are exhausted, overworked, and going mad. The grunts, Rickles (Ralph Marrero) and Steel (G. Howard Klar), leer at Sarah and make perverse jokes, cackling in maniacal, crazed laughter that reveals their constant state of terror. These performances recall the weasels from Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1985), whose laughter will get them killed. The separatists wish they were on a beach somewhere, soaking up sunshine for the rest of their days. But most of the film follows Sarah, who finds herself struggling to find some common ground between them all, some civility they can all adhere to, except there’s none left. “What you’re doing is a waste of time,” John tells her. “And time is running out.”

Civilization has collapsed, and Day of the Dead’s characters reflect that. Romero’s commitment to portraying characters on the brink of madness can be jarring but no less representative of humanity’s breaking point. Rhodes’ short temper and penchant for shouting expletive-laden orders capture his loss of control. “I’m running this monkey farm now, Frankenstein, and I wanna know what the fuck you’re doing with my time!” he yells. His soldiers appear as some combination of overweight, unshaven, undisciplined, and stoned. If Marrero and Klar threaten to destabilize the film with their over-the-top performances, the effect is intentional. Always laughing and over-emphasizing each line of dialogue, the military characters are given wild and uncontrollable personas of violence, racism, and rapey intentions. They’re also fixated on preserving whatever scrap of power they retain. What results is unbearably aggressive, intolerant, and illogical lines shouted at civilians and scientists, who have barely retained their sanity themselves. Romero’s commentary on the perverse military drive might be undone by the heightened performances on the initial viewing. Still, their fanatical and excessive style also reflects how all signs of civility and order have disappeared from human interactions.

If the military men have slipped into madness, Logan has descended into his own brand of mania. His experiments into zombie physiology attempt to access the shared human-zombie “primordial” brain, but his need to understand zombies has distracted him from finding a solution. So instead, Logan seeks to control them by making them behave in a civilized manner. “Civilized behavior is what distinguishes us from the lower forms,” Logan explains at one point. “It’s what enables us to communicate, to go about things in an orderly manner, without attacking each other like beasts.” He attempts to prove his theories with “Bub,” a zombie he domesticates, to show that the undead retain some memory of their former lives (an idea Romero probed again in Land of the Dead). Logan teaches Bub tricks like a parent teaching a child. “Father is quite proud of you,” he tells Bub in a parental tone before rewarding him with human flesh butchered from recently dead soldiers. Sherman Howard plays Bub, giving the best zombie performance put to film (aside from Billy Connolly’s undead tour de force in 2006’s Fido). Howard adds an underlying emotionalism to his distant zombie expressions through inches of make-up. Other thinking zombies, too, suggest that zombies are not without feelings. Note a zombie who shows fear when captured or a misbehaving zombie who looks dismayed when Logan turns out the lights and tells him, “Think about what you’ve done.”

Scenes with Bub make Day of the Dead something visionary, less commercial, more than just an exercise in rotting dead bodies lurking about in crowds, blood oozing from every orifice, eating every living thing they encounter. Romero advances ideas about how humanity chooses to see marginalized groups as Others by creating genuine sympathy for a zombie character who shows consciousness (Bub reacts to music, salutes a soldier, reels after losing Logan, and takes revenge on Rhodes for killing his makeshift father). Romero taps into a condition of Reagan’s America, in which the lines of ideological demarcation deepen so that civilization no longer recognizes itself. These divisions have only intensified the culture war in the last few decades, particularly during the Trump presidency. They have led to further division and increased distrust in institutions that cannot communicate or demonstrate a willingness to compromise, evident in the film when all civility between the scientific and military personnel comes crashing down. The failure of civilization felt imminent for Romero in 1985, and as a result, Day of the Dead feels achingly relevant today. Accordingly, John and McDermott’s plan to escape with Sarah to an island paradise far away from these crumbling institutions seems all the more idyllic.

Scenes with Bub make Day of the Dead something visionary, less commercial, more than just an exercise in rotting dead bodies lurking about in crowds, blood oozing from every orifice, eating every living thing they encounter. Romero advances ideas about how humanity chooses to see marginalized groups as Others by creating genuine sympathy for a zombie character who shows consciousness (Bub reacts to music, salutes a soldier, reels after losing Logan, and takes revenge on Rhodes for killing his makeshift father). Romero taps into a condition of Reagan’s America, in which the lines of ideological demarcation deepen so that civilization no longer recognizes itself. These divisions have only intensified the culture war in the last few decades, particularly during the Trump presidency. They have led to further division and increased distrust in institutions that cannot communicate or demonstrate a willingness to compromise, evident in the film when all civility between the scientific and military personnel comes crashing down. The failure of civilization felt imminent for Romero in 1985, and as a result, Day of the Dead feels achingly relevant today. Accordingly, John and McDermott’s plan to escape with Sarah to an island paradise far away from these crumbling institutions seems all the more idyllic.

Lofty ideas aside, the make-up effects alone have sustained Day of the Dead’s status as a cult favorite. It remains Romero’s grossest, goriest, and most yuck-inducing effort, thanks to the demented imagination of make-up guru Tom Savini. Heading a group of top make-up effects artists, including The Walking Dead’s Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger, Savini created viscera with a combination of latex and foul-smelling pig intestines to top Romero’s other of the Dead entries before and after. There are countless moments of shocking effects throughout, but one scene must be mentioned: the moment when a zombie-patient on an operating table turns on his side to reach for a potential meal, and his insides slop out with a gooey schluck when they hit the floor. Romero and Savini give us zombies that dismember several human victims, tear them from the inside out, rip a head off by pulling at the eyes, and eat a man’s guts as he shouts, “Choke on ’em!” And, of course, every Romero zombie film features a feeding frenzy montage at the end; this one is particularly nasty.

Romero called Day of the Dead his favorite of his films. It’s certainly his most challenging. Besides Sarah and the separatists, the characters prove difficult to identify with, while Bub might be the most innocent character on the screen. Doubtless, that’s the point. Romero shows how people prefer to use, exploit, and abuse one another rather than help each other. The film’s meaning isn’t as plain as his notes on consumerism in Dawn of the Dead or society’s racial violence in Night of the Living Dead; the director circulates several central themes that portray how civilization hangs by a thread, and humanity’s descent has snipped the line. The undead represent how civility has been replaced by rage and intolerance, which has caused institutions to fail and eliminated any hope for societal wholeness. Romero wishes for a world where the masses regain control over those same crumbling and untrustworthy institutions. Alternatively, he hopes that people can find a way to escape somewhere beyond their reach. Taking the most reflective, philosophical approach in any of his zombie movies, Day of the Dead is an imperfect work featuring big ideas, several wonderfully horrid individual scenes, and gory zombie effects unmatched in the master’s career.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted on Patreon.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review