The Definitives

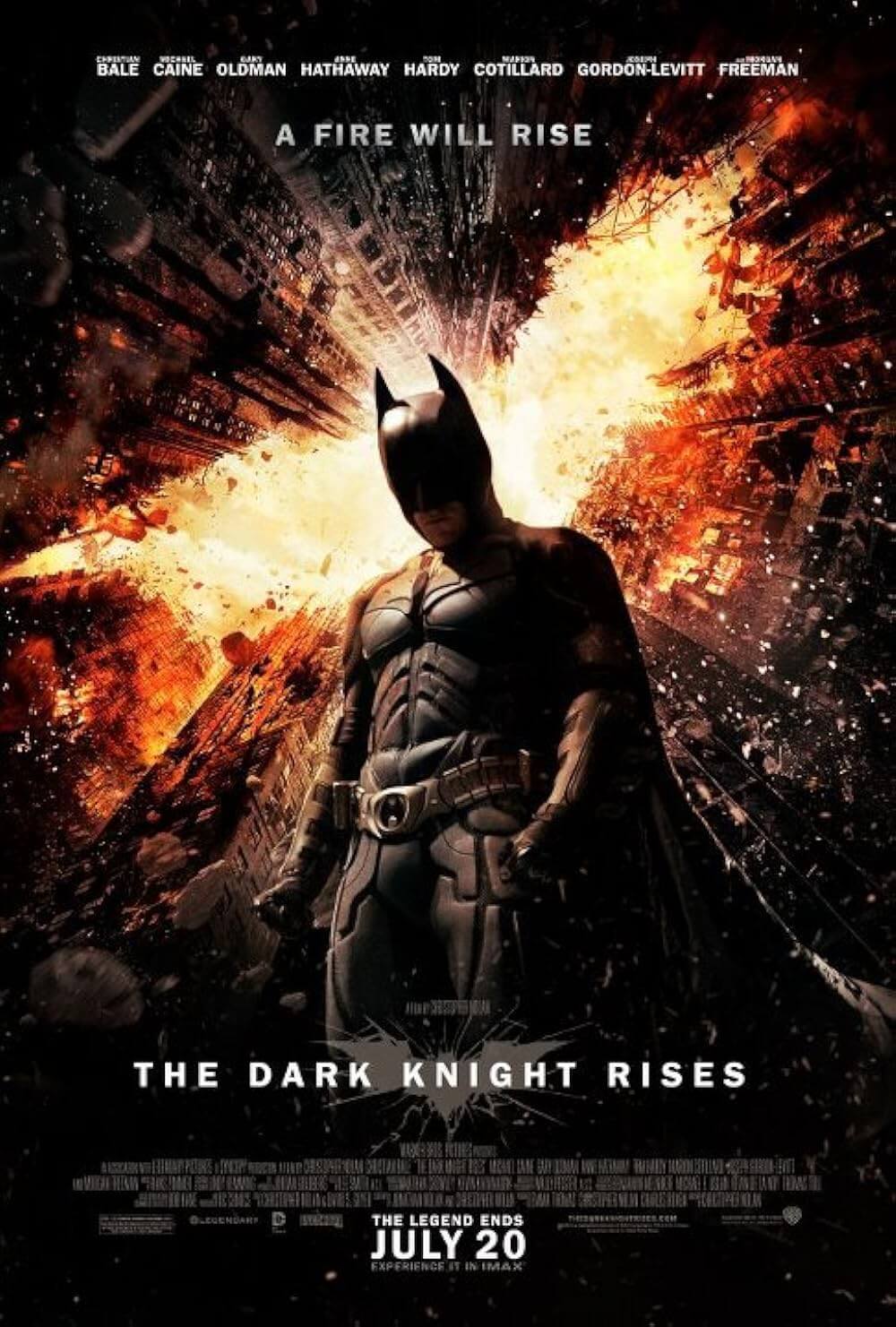

The Dark Knight Rises

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In The Dark Knight Rises, Gotham City’s Caped Crusader transforms from the symbol of heroism and hope established in Batman Begins, whose endurance was so unsparingly tested and thus entrenched by The Dark Knight, to become something else entirely: legend. Christopher Nolan’s final act in his trilogy rises above the usual limitations of the third entry in a series by binding all three together, expanding what came before, and turning three individual stories into a superior, overarching narrative. As a single film, it is the most massive of The Dark Knight Trilogy in sheer length and scope. Set it aside from its predecessors, and Nolan has constructed an ambitious epic of grand dramatic and visual spectacles. With equal attention paid to the texture of his narrative as well as the sweeping exhibition of his picture, Nolan further demonstrates his own exceptional artistry as a storyteller and skill as a filmmaker by binding the experience with socially relevant themes matched only by the film’s humanity. Still, however singular this and his other Batman films may be on their own, they develop into something far more impressive as a whole.

What Nolan’s third Batman picture realizes is the promise made by Bruce Wayne, played by Christian Bale in the best of his three performances as Wayne, in that now-iconic scene from Batman Begins, where the young hero-in-training flies back to Gotham City to become a symbol for his city. Wayne declares, “People need dramatic examples to shake them out of apathy and I can’t do that as Bruce Wayne. As a man, I’m flesh and blood. I can be ignored. I can be destroyed. But as a symbol… As a symbol, I can be incorruptible. I can be everlasting.” In Nolan’s first Batman film, the apathy in Gotham’s citizens rested in their willingness to ignore crime-ridden city streets and refuse to combat rampant corruption. In that same sense, when at the end of The Dark Knight our hero enlists Gary Oldman’s Commissioner Jim Gordon to lie to the people of Gotham City and declare that Batman was responsible for the death of their “White Knight” Harvey Dent, he made a false martyr and artificial heroic example out of Dent, and instead condemned the true hero to seclusion. Eight years have passed when The Dark Knight Rises opens, and much of Gotham still believes Gordon’s lie. They even thrive in peacetime, without need for a Caped Crusader to protect them, their apathy fed by the illusion of their safety; while, without need for Batman, Bruce Wayne has grown so complacent that those he leaves in charge have stopped funding an orphanage in his name.

With the loss of their hero, Gotham politicians have stepped forward to establish a “Dent Act” mandating that those involved in organized crime will be denied certain rights and subject to stricter penalties. Now Gotham’s Blackgate Prison teems with criminals while her streets remain quiet, just as the Patriot Act has placed countless suspected terrorists in a detention camp on Guantánamo Bay. Content in their delusion of harmony, Gotham survives on what Bane (Tom Hardy), tortured-voiced terrorist leader for The League of Shadows, calls “borrowed time”. Bane might have quoted Benjamin Franklin, who once wrote, “Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.” The modern relevancy of Bane’s words is, perhaps unconsciously, tapped by Christopher and Jonathan Nolan’s screenplay, which, in its subtext, compares the setting of The Dark Knight Rises to a post-9/11 America in which the resident Gothamites have given up certain freedoms and overlooked moral conundrums for a feeling of security. In other words, our post-9/11 justifications for the limitation of certain basic rights create another kind of enemy in ourselves, which in turn represents a form of soul-corruption. This corruption may not be unfettered organized crime for America, but it is corruption nonetheless.

With the loss of their hero, Gotham politicians have stepped forward to establish a “Dent Act” mandating that those involved in organized crime will be denied certain rights and subject to stricter penalties. Now Gotham’s Blackgate Prison teems with criminals while her streets remain quiet, just as the Patriot Act has placed countless suspected terrorists in a detention camp on Guantánamo Bay. Content in their delusion of harmony, Gotham survives on what Bane (Tom Hardy), tortured-voiced terrorist leader for The League of Shadows, calls “borrowed time”. Bane might have quoted Benjamin Franklin, who once wrote, “Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.” The modern relevancy of Bane’s words is, perhaps unconsciously, tapped by Christopher and Jonathan Nolan’s screenplay, which, in its subtext, compares the setting of The Dark Knight Rises to a post-9/11 America in which the resident Gothamites have given up certain freedoms and overlooked moral conundrums for a feeling of security. In other words, our post-9/11 justifications for the limitation of certain basic rights create another kind of enemy in ourselves, which in turn represents a form of soul-corruption. This corruption may not be unfettered organized crime for America, but it is corruption nonetheless.

The brothers Nolan admit to deriving the stakes of their screenplay from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, an allegorical text in which the French aristocracy’s undermining of the proletariat leads to the French Revolution, and as such their example serves a reflection of similar social circumstances in England. By association, one cannot help but see Gotham as a synecdoche of America in The Dark Knight Rises, with the film’s conflicts serving up direct but oftentimes symbolic correlations to the United States’ sociopolitical conditions. The picture’s themes of revolution, resurrection, sacrifice, deception, and symbolism, each heavily used in Dickens’ novel, presents a kind of novelistic approach to filmmaking wherein Nolan has resisted making his commentary oblique or obvious, but nonetheless channels certain imagery that forces a debate between Leftists, Right-wingers, and everyone in-between. For example, when Bane first emerges in Gotham, he launches an attack on the Gotham City Stock Exchange and the visual imagery becomes eerily prophetic, since the Nolans wrote their script long before the Occupy Wall Street movement began, but the correlation remains undeniable. Whether intentional or by coincidence, the film becomes Nolan’s most political.

There is also an effort on Nolan’s part to close out his trilogy with a circular sense of finality; he returns to the conflict of Batman Begins through Bane’s undertaking of Ra’s al Ghul’s master plan of destroying Gotham City. It takes another kind of symbol altogether to shake Gotham out of its peacetime complacency, and Bane provides that symbol—an emblem of fear and terror who orchestrates a mass scale scheme to destroy Gotham first in spirit and then by way of a nuclear explosion. A character whose mystique is fuelled by rumors of his origin and the mystery of his appearance, he dons a tubular mask over his nose and mouth that wraps around his bald head. When he escapes CIA captivity in the film’s opening sequence, he admits, “No one cared who I was until I put on the mask.” Characters speak about Bane like a monster in a fairy tale, much the way Gothamites talk about Batman. They say Bane was born in and escaped from a cylindrical prison pit, designed with an open-air top for inmates to look up and see hope; the prison encourages escape attempts, but no one ever has, save for a child, whom the storytellers claim is Bane. Riding this wave of underworld rumor, Bane attacks Gotham on multiple fronts at once. Through ties made by corrupt Wayne Enterprises board member John Daggett (Ben Mendelsohn), he bankrupts Bruce Wayne and leaves Wayne Enterprises in Daggett’s control. But rather than financial gain, Bane has used Daggett to access the company’s hidden stockpile of Applied Sciences weaponry; most importantly, a shelved clean energy generator he reformats into a bomb. In his plan, Bane at once confronts our greatest fears in modern American society: terrorism and economic recession.

There is also an effort on Nolan’s part to close out his trilogy with a circular sense of finality; he returns to the conflict of Batman Begins through Bane’s undertaking of Ra’s al Ghul’s master plan of destroying Gotham City. It takes another kind of symbol altogether to shake Gotham out of its peacetime complacency, and Bane provides that symbol—an emblem of fear and terror who orchestrates a mass scale scheme to destroy Gotham first in spirit and then by way of a nuclear explosion. A character whose mystique is fuelled by rumors of his origin and the mystery of his appearance, he dons a tubular mask over his nose and mouth that wraps around his bald head. When he escapes CIA captivity in the film’s opening sequence, he admits, “No one cared who I was until I put on the mask.” Characters speak about Bane like a monster in a fairy tale, much the way Gothamites talk about Batman. They say Bane was born in and escaped from a cylindrical prison pit, designed with an open-air top for inmates to look up and see hope; the prison encourages escape attempts, but no one ever has, save for a child, whom the storytellers claim is Bane. Riding this wave of underworld rumor, Bane attacks Gotham on multiple fronts at once. Through ties made by corrupt Wayne Enterprises board member John Daggett (Ben Mendelsohn), he bankrupts Bruce Wayne and leaves Wayne Enterprises in Daggett’s control. But rather than financial gain, Bane has used Daggett to access the company’s hidden stockpile of Applied Sciences weaponry; most importantly, a shelved clean energy generator he reformats into a bomb. In his plan, Bane at once confronts our greatest fears in modern American society: terrorism and economic recession.

Bruce Wayne now suffers from his own apathy, too, providing a stand-in for today’s 1% ruling class of super-rich who have the facility to make grand changes but instead make themselves richer. Since the death of Rachel Dawes, Wayne has become a recluse, his body weakened and frail from the previous years of strenuous battles as Batman, and his fortune depleted following a failed clean energy initiative spearheaded by board member Miranda Tate (Marion Cotillard). Wayne is prompted out of his self-imposed retirement when, during a banquet to celebrate Dent’s memory at Wayne Manor, cat burglar Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway, devilishly charming) steals Wayne’s fingerprints so Daggett can carry out his plan to liquidate Wayne’s assets. Wayne tracks Kyle to a fundraising dinner and they share a dance. Her contempt for his class is unmistakable, as is her involvement with Bane when she warns, “There’s a storm coming, Mr. Wayne. You and your friends better batten down the hatches, because when it hits, you’re all going to wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” Kyle stands for the angered lower classes whose hard times send her teetering between her moral center and her cunning, often criminal survival instincts.

With this and Bane’s arrival, the out of practice hero resolves that his city needs Batman again, despite concerned objections from lifelong butler Alfred (Michael Caine), who refuses to stand by and watch Wayne willfully destroy himself by going up against Bane and his superior forces. Alfred wants more for his Master Wayne than to watch him follow his own terrible self-sacrificing mission; he hoped Bruce would someday move on, get married, and disappear into another life altogether. But Bruce clings to the memory of Rachel. Herein resides Nolan’s very human take on a hero’s life, as Alfred is a devoted servant but he also wants the best for the boy he helped raise, which does not include watching him destroy himself as Batman. Instead, Alfred refuses to bear witness, and after his last effort to dissuade Bruce by confessing to him how Rachel had chosen Dent over him, Alfred abandons his post. In Nolan’s fixed drive toward realism in this superhero trilogy, he acknowledges how a hero cannot remain so forever; a recurring theme in The Dark Knight Rises is how a limit exists for what one human can endure, be it physically or emotionally, and those limits require necessary changes roused from moving examples.

With this and Bane’s arrival, the out of practice hero resolves that his city needs Batman again, despite concerned objections from lifelong butler Alfred (Michael Caine), who refuses to stand by and watch Wayne willfully destroy himself by going up against Bane and his superior forces. Alfred wants more for his Master Wayne than to watch him follow his own terrible self-sacrificing mission; he hoped Bruce would someday move on, get married, and disappear into another life altogether. But Bruce clings to the memory of Rachel. Herein resides Nolan’s very human take on a hero’s life, as Alfred is a devoted servant but he also wants the best for the boy he helped raise, which does not include watching him destroy himself as Batman. Instead, Alfred refuses to bear witness, and after his last effort to dissuade Bruce by confessing to him how Rachel had chosen Dent over him, Alfred abandons his post. In Nolan’s fixed drive toward realism in this superhero trilogy, he acknowledges how a hero cannot remain so forever; a recurring theme in The Dark Knight Rises is how a limit exists for what one human can endure, be it physically or emotionally, and those limits require necessary changes roused from moving examples.

In his reemergence, Batman wavers as his body and spirit suffer from entropy, and his inadequate attempt to reclaim his former glory is not enough to match Bane’s prowess. Nevertheless, he willingly follows Catwoman, who agrees to lead him to Bane on false pretenses—to a fateful one-on-one in which Batman is outmatched. His back broken and defeated in a plot point inspired from the famous Batman comic storyline Knightfall, Bruce Wayne is placed in the same pit from where Bane had supposedly escaped. Bane’s prison is designed to obliterate one’s resolve by crushing their hope. Here, Bane sentences Wayne to watch as he levels Gotham, and only after Wayne’s spirit is broken will he be killed. But, as time passes, Wayne’s body and soul gradually heal as he becomes aware of how his decision to rely on Dent’s faux heroic symbol betrayed his original understanding of what being Gotham’s symbol meant. Only by shaking himself out of apathy and accepting the possibly mortal task of being Gotham’s true symbol can he escape and become the crusader his city needs. With his own spiritual resurrection, he returns to find Gotham in shambles.

But while Batman recovers in the pit, Bane’s plan for Gotham unfurls with little possible resistance. Bridges connecting the island city to the mainland have been blown, almost the entire police force is trapped underground when they go looking for Bane’s sewer complex, and Bane releases Blackgate’s inmate population after announcing Gordon’s admitted lies about Harvey Dent’s death. Gotham is in chaos, held hostage by an unidentified citizen with his finger on a button. With this, subsets of people retain hope for their true hero, Batman, to return. Among the believers is John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), a good cop who long ago figured out Bruce Wayne is Batman but kept the secret. As an orphan, Blake saw Wayne carrying a false smile, behind which he recognized his own feelings of anger and a lust for vengeance, as his cop father died tragically as well. “You get to learn to hide the anger, practice smiling in a mirror. It’s like wearing a mask,” Blake explains. Both men of broken families, both accustomed to wearing masks, it seems only fitting that Blake would be inspired by Wayne’s example, and leave chalk Bat-Symbols around Gotham to inspire hope in her citizens. Even so, Bane has called for Gotham’s lower classes to rise up and take retribution on the elite, tearing them from their homes to be placed on makeshift trials for their social crimes—their maniacal judgment carried out by none other than madman psychopharmacologist Scarecrow (Cillian Murphy).

But while Batman recovers in the pit, Bane’s plan for Gotham unfurls with little possible resistance. Bridges connecting the island city to the mainland have been blown, almost the entire police force is trapped underground when they go looking for Bane’s sewer complex, and Bane releases Blackgate’s inmate population after announcing Gordon’s admitted lies about Harvey Dent’s death. Gotham is in chaos, held hostage by an unidentified citizen with his finger on a button. With this, subsets of people retain hope for their true hero, Batman, to return. Among the believers is John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), a good cop who long ago figured out Bruce Wayne is Batman but kept the secret. As an orphan, Blake saw Wayne carrying a false smile, behind which he recognized his own feelings of anger and a lust for vengeance, as his cop father died tragically as well. “You get to learn to hide the anger, practice smiling in a mirror. It’s like wearing a mask,” Blake explains. Both men of broken families, both accustomed to wearing masks, it seems only fitting that Blake would be inspired by Wayne’s example, and leave chalk Bat-Symbols around Gotham to inspire hope in her citizens. Even so, Bane has called for Gotham’s lower classes to rise up and take retribution on the elite, tearing them from their homes to be placed on makeshift trials for their social crimes—their maniacal judgment carried out by none other than madman psychopharmacologist Scarecrow (Cillian Murphy).

To be sure, Nolan’s film suggests a certain level of revolution is needed to shake the ruling class out of apathy, but that it should be conducted circumspectly. He understands the populace’s anger with the spoiled upper classes, as he makes Kyle empathetic in her search to escape her sordid past, no matter the means, and reform. As much as Kyle almost prefers the lawless nature of Bane’s rule, she recognizes that it’s anarchy and, with Batman’s inevitable return to Gotham, forms an alliance to restore order. The film’s cautionary tale for the classes aligns with that of Dickens: The nature of any power structure, be it government or superhero overseer, is to fix something only after it breaks. In The Dark Knight Rises, everyone is apathetic and complacent when the film opens, and it takes something terrible to occur before action is taken. Nolan outlines a historical trend where one evil is destroyed and another is created in the process of demolishing it, whereas the film offers that a constant watchdog presence on the outside, like Batman, might dissuade such injustices. This is the appeal of an everlasting superhero, and thus the symbol of Batman—a metaphor suggesting that as a society we can never turn a blind eye to injustice or it begins to corrupt and take over. Nolan illustrates how fragile the illusion of security can be, because any individual, city, or country is vulnerable, and the system on which we stand is always cracking under our feet. How appropriate then that Scarecrow sentences Gotham’s perceived corrupt to death or exile by sending them out to walk on thin ice to their unavoidable demise. Moreover, cracking ice is the same imagery that form’s the Bat-Symbol at the film’s opening.

The film’s final battle is marked by Batman announcing his return to Gotham when he sets a massive Bat-Symbol ablaze. For Blake and Gordon, those who have continued to fight Bane despite impossible odds, his reappearance creates countless reinforcements in Gotham’s police and everyday citizens who now believe their fight isn’t hopeless. If it was not apparent before these scenes, Nolan amplifies the tension and action in his finale to accelerate The Dark Knight Rises into a war film. The picture’s slow-burning tension grows for over two hours by the time Batman returns to Gotham, and Nolan’s directorial showmanship offers armies of police and Bane’s minions colliding in the streets, and at their center is another moving clash between Batman and Bane. Missiles are launched and vehicles give chase; the time bomb ticks away with mere minutes until everyone is blown to oblivion. The momentum never slows, and Nolan’s $250 million budget hides all signs of how he put these bravado moments together. Pure awe might take over if the film did not so carefully involve us in the fates of everyone onscreen.

The film’s final battle is marked by Batman announcing his return to Gotham when he sets a massive Bat-Symbol ablaze. For Blake and Gordon, those who have continued to fight Bane despite impossible odds, his reappearance creates countless reinforcements in Gotham’s police and everyday citizens who now believe their fight isn’t hopeless. If it was not apparent before these scenes, Nolan amplifies the tension and action in his finale to accelerate The Dark Knight Rises into a war film. The picture’s slow-burning tension grows for over two hours by the time Batman returns to Gotham, and Nolan’s directorial showmanship offers armies of police and Bane’s minions colliding in the streets, and at their center is another moving clash between Batman and Bane. Missiles are launched and vehicles give chase; the time bomb ticks away with mere minutes until everyone is blown to oblivion. The momentum never slows, and Nolan’s $250 million budget hides all signs of how he put these bravado moments together. Pure awe might take over if the film did not so carefully involve us in the fates of everyone onscreen.

For Wayne, this citywide battle against Bane becomes a fulfillment of his vow from Batman Begins to become Gotham’s true symbol, no matter the cost. In another way, Nolan returns the conflict to his first film even more so when he reveals how Batman’s victory represents the downfall of The League of Shadows, represented by Ra’s al Ghul’s daughter, Talia, who has infiltrated Wayne Enterprises as Miranda Tate. With Bane—the savior figure who helped her escape the prison pit—Talia has devised the stages of Gotham’s doom. And with Batman’s seeming self-sacrifice, when he flies Bane’s time bomb out into the bay away from the city with no hope for making it back, the hero inscribes himself into legend. In the aftermath, Gotham erects a statue of the Batman. Wayne’s assets seized or donated by his will, Wayne Manor becomes an orphanage, while John Blake, also a former orphan, follows Wayne’s cue to find the newly rebuilt Batcave. With this, Batman’s legend inspires Blake to follow his example in whatever form he chooses—whether he adopts Batman’s garb, or finds an entirely new alter-ego such as Robin or Nightwing—using Wayne’s means. Whatever the form, the legend lives on and has inspired followers to create a better Gotham City.

And with this, Nolan’s trilogy finally accomplishes what Wayne set out to do in Batman Begins, ending the series hopeful that Blake will take over, inspired by Wayne’s example. But more than a symbolic conclusion, Nolan constructs a deeply emotional finish where, in a final scene, Alfred sees Bruce and Selina at an open-air café in Florence, having successfully escaped their former identities. This was Alfred’s long-held wish for the boy he helped raise and the man he refused to watch commit virtual suicide for an ideal. And how fitting a match, since both Bruce and Selina each wanted and needed to move on to save themselves. The prospect of Bruce finally able to progress beyond the anger that created Batman is hopeful, and an endearingly pleasant revelation for the wounded Bruce Wayne character, whose emotional happiness in so many Batman storylines is often secondary to the responsibilities of his heroic alter-ego. Nolan’s genius in this trilogy has been to apply a sense of realism to his approach, emotional realism most of all; and with this final entry he compounds streams of evocative, symbolic, highly interpretable imagery with an emotional center than overwhelms the viewer during the film’s last scenes.

And with this, Nolan’s trilogy finally accomplishes what Wayne set out to do in Batman Begins, ending the series hopeful that Blake will take over, inspired by Wayne’s example. But more than a symbolic conclusion, Nolan constructs a deeply emotional finish where, in a final scene, Alfred sees Bruce and Selina at an open-air café in Florence, having successfully escaped their former identities. This was Alfred’s long-held wish for the boy he helped raise and the man he refused to watch commit virtual suicide for an ideal. And how fitting a match, since both Bruce and Selina each wanted and needed to move on to save themselves. The prospect of Bruce finally able to progress beyond the anger that created Batman is hopeful, and an endearingly pleasant revelation for the wounded Bruce Wayne character, whose emotional happiness in so many Batman storylines is often secondary to the responsibilities of his heroic alter-ego. Nolan’s genius in this trilogy has been to apply a sense of realism to his approach, emotional realism most of all; and with this final entry he compounds streams of evocative, symbolic, highly interpretable imagery with an emotional center than overwhelms the viewer during the film’s last scenes.

However readable The Dark Knight Rises may be from an array of political perspectives, the film remains a powerful piece of dramatic storytelling that, much like Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, transcends what it means to be a comic book adaptation, and in broader terms a Hollywood motion picture. Christopher Nolan elevates his genre and stretches the limits of blockbuster filmmaking with a boldly artistic, wildly ambitious production that is as evocative as it is impressive, while his completion of the series constitutes one of the most profoundly gratifying trilogies in film history—a trifecta achievement through which he retains remarkable consistency from film to film, though they were shot years apart. Nolan’s enduring philosophical exploration of superhero mythos and stunning cinematic stagecraft thrills like no other and will doubtless never be matched in its intelligence or grandiosity. The director’s grave treatment, accomplished filmmaking, and daring aspirations have made The Dark Knight Rises a modern masterpiece. Just as the film’s enduring hero does, Nolan’s trilogy has established a contemporary legend.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review