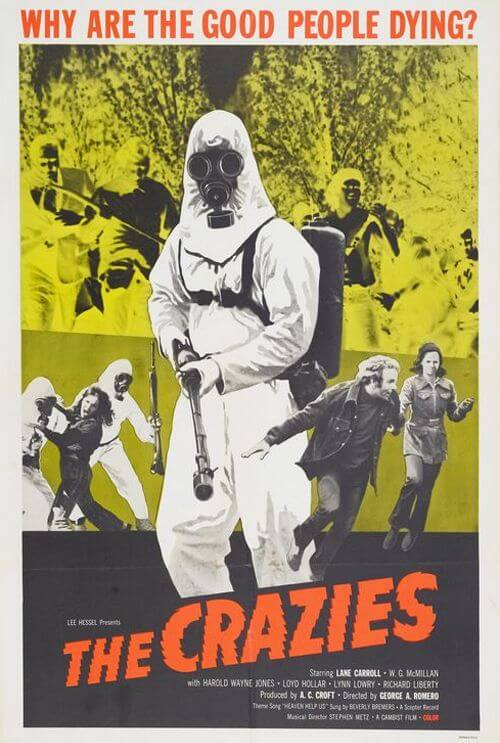

The Crazies

By Brian Eggert |

As the originator of the contemporary zombie horror subgenre, George A. Romero made non-zombie associated works in-between his more popular zombie titles—mostly forgettable schlock like Season of the Witch (aka Hungry Wives), a tale of lonely housewives who resort to witchcraft to cure their boredom. Romero’s 1973 film The Crazies came between his two most renowned films, Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, when the director was slowly realizing that he had a particular story he wanted to tell. And so, the film plays out like a thinly veiled zombie horror spectacle, with flesh-eating undead replaced by victims of a disease that’s driven them mad.

Apart from lacking oodles of gore, the message of the film aligns with the social commentary of Romero’s 1985 release, Day of the Dead. Both make harsh criticisms of government organizations, the lack of military control and preparation implemented in emergency situations, and the military’s deficient respect for science in a martial law situation. Both movies find dogmatic army men disregarding the advice of a knowing scientist in favor of sustaining their military control, leading to utter chaos as a result. It’s a small wonder that Romero hasn’t designed one of his more recent zombie films to reflect a Katrina-like disaster (though such a setting would require a budget that the director doesn’t usually have), as the potential allegory seems ripe for his taking.

The landscape is familiar Romero territory—on the director’s home turf of the Pennsylvania farmlands, in a small American town filled with rednecks and easily influenced masses. A military plane crashes on the outskirts of town, leaving a highly contagious engineered bio-weapon called “Trixie” (the film’s original title was Code Name: Trixie) in the town’s water, its citizens none the wiser to their impending exposure. Victims become raving lunatics, behaving anywhere from euphoric to nonsensical to ultra-violent. When symptoms begin to show the military swoops in and declares martial law, closes down the town, and places a barricade two miles around the area to prevent escape, and thus the disease from spreading. Their quarantine is protected by a bomber circling overhead, waiting to drop nukes should the infection approach the perimeter.

The heroes, per usual Romero tropes, are comprised of a small group of resourceful survivors who know enough to avoid both the military and other people, infected or not. The acting is hammy and laughable at times, but what can one expect from 1970s exploitation cinema? Part-time firefighter David (W.G. McMillan, who sports a distractingly ‘70s unibrow) and his pregnant nurse girlfriend Judy (Lane Carroll) team up with roughneck friend Clank (Harold Wayne Jones) to escape the authorities and infection. They seem to be naturally immune to Trixie, but as they travel across the terrain it becomes apparent they are not. Joining them are Artie (Richard Liberty) and Kathy (Lynn Lowry), a father-daughter pair whose relationship takes a disturbing twist as the disease takes them over, leaving them susceptible to incestuous impulses.

Meanwhile, back in town, the ever-shouting scientists scramble to find a cure, but the military doesn’t yet have the equipment needed to research one. The ineffectual decision-making from the Man in Charge, Major Ryder (Harry Spillman), leads to Colonel Peckem (Lloyd Hollar) being flown in to bring order to the situation, though the brash actions of military bureaucracy previous to his command leave him scrambling for order. His men torch the bodies of the infected (not unlike zombie corpses burned in Night of the Living Dead), robbing them of loose cash before setting them afire. The streets are filled with panic; a priest burns himself alive in protest (a clear allusion to the self-immolation of Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc in 1963) though it’s not clear if he’s acting out of demonstration or as a reaction to the infection. Civilians protest to the way they’re treated, but the robotic, authority-driven power of the gas-masked soldiers cannot be reasoned with—as demonstrated when the military’s top Trixie scientist is mistaken for a civilian and despite his protests thrown into a room filled with raging infected.

Meanwhile, back in town, the ever-shouting scientists scramble to find a cure, but the military doesn’t yet have the equipment needed to research one. The ineffectual decision-making from the Man in Charge, Major Ryder (Harry Spillman), leads to Colonel Peckem (Lloyd Hollar) being flown in to bring order to the situation, though the brash actions of military bureaucracy previous to his command leave him scrambling for order. His men torch the bodies of the infected (not unlike zombie corpses burned in Night of the Living Dead), robbing them of loose cash before setting them afire. The streets are filled with panic; a priest burns himself alive in protest (a clear allusion to the self-immolation of Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc in 1963) though it’s not clear if he’s acting out of demonstration or as a reaction to the infection. Civilians protest to the way they’re treated, but the robotic, authority-driven power of the gas-masked soldiers cannot be reasoned with—as demonstrated when the military’s top Trixie scientist is mistaken for a civilian and despite his protests thrown into a room filled with raging infected.

There’s some confusion in the script about whether or not Trixie is a “virus” or a “bacteriological weapon.” The film refers to Trixie as both types of contamination, but obviously, bacteria is not a virus nor vice versa. So at one moment, the government scientists worry about a vaccine, and the next they’re talking about getting antibiotics. Whether or not this was an intentional detail on Romero’s part to illustrate the botched, blundering military op, we cannot be sure. The error is most likely a result of Romero not doing his Biology 101 homework before writing the script. Though we’re meant to believe the military and scientists behind the quarantine are overwhelmed and at times incompetent, it’s doubtful that they were meant to be that incompetent.

But then, such errors come with the territory for this sort of low-budget, grindhouse-worthy fare, don’t they? Regardless of his success on Night of the Living Dead five years earlier, Romero was no more prosperous financially, except perhaps for the notoriety of releasing a hit cultural phenomenon. His budget for The Crazies was a mere $270,000, which is reasonably extended given the scope of the picture. Shooting in Evans City, Pennsylvania, Romero relied on volunteer extras to play the frenzied masses, including high school teenagers as the gas-masked government goons. He got lucky when the local firefighters set an old abandoned farmhouse on fire for practice; the director shot needed scenes around the burning building. Otherwise, such pyrotechnics were outside of his resources.

These innovations are crucial in low-budget filmmaking, and Romero is a master of stretching a meager budget. With the exception of Land of the Dead, each Romero film has boasted minor financing yet contains a striking visual style, both in terms of composition and the special FX details that appear onscreen. Furthermore, Romero’s editing mixes up the C-grade production value, rendering it at a frenetic, sometimes overly choppy pace. His cutting may be the foremost reason to seek out this film, particularly in a staccato scene that snaps back and forth between brainstorming military officials and the execution of their preparations. The cheap film shock and palpably economical production have less presence during a viewing because Romero, aside from being a master of horror, is also a master of disguising his limitations through his ingenuity as an editor. Even if Romero steals from himself to come up with his plot and themes for The Crazies, the film deserves its place as a cult classic on a purely cinematic level.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review