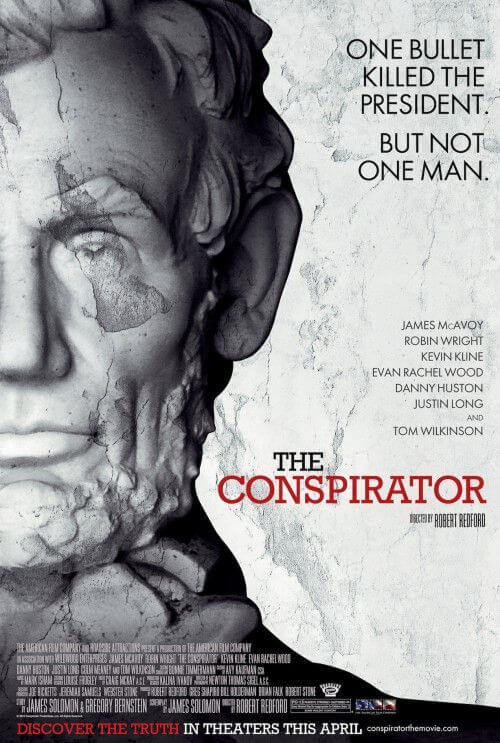

The Conspirator

By Brian Eggert |

Robert Redford’s The Conspirator marks the debut release from The American Film Company, a new studio dedicated to presenting accurate historical subject matter within the guise of Hollywood movies. These haughty but admirable intentions deliver a motion picture with the stuffy manner of historical reenactment, though it recalls a devastating incident in US history that has since been forgotten by the general public. What’s more, the film contains crucial modern parallels that suggest the country hasn’t changed much in the last century-and-a-half. Director Redford and screenwriter James D. Solomon don’t over-emphasize these parallels through suggestive dialogue, though anyone watching would be blind not to see them.

The year is 1865. America’s open wound from the Civil Wars still throbs, with much more healing to do before her people can move forward. When Abraham Lincoln is assassinated, the wound reopens, perhaps deeper than before, and inflexible Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (Kevin Kline) is desperate to stitch it up and move forward. His revenge-hungry government gathers up the conspirators who, along with the shot-dead John Wilkes Boothe, organized the assignation of Lincoln, and intends to hang the lot after a swift conviction. Among them is Mary Surratt, whose wanted son John allegedly helped organize the scheme. Though legally the suspected conspirators are entitled to a civilian trial, Stanton insists it be held in military court, no matter how unconstitutional it may be, to allow the American people swift justice.

Enter young Union war hero and lawyer Frederick Aiken (James McAvoy), who’s referred to the case by idealistic Maryland senator Reverdy Johnson (Tom Wilkinson). Though devoted to the North and pained by the concept of defending Surratt (Robin Wright Penn), Aiken begins to understand why Johnson believes the trial is a Constitutional miscarriage. The drumhead-like procession (reminiscent of the one in Kubrick’s Paths of Glory) is merely a formality to disguise what would otherwise be a lynch mob. Aiken’s spirited defense becomes career suicide whether he wins or loses, and he’s encouraged by friends to step down. He doesn’t, and indeed all of Stanton’s powers guarantee Surratt is convicted of treason and made to be the first woman hanged by the US government—even though Aiken secures a writ of habeas corpus, which is inexplicably denied by President Johnson.

Throughout the course of the trial, ineffectual melodramatic subplots, such as one involving Aiken’s sweetheart (Alexis Bledel) leaving him during the trial’s proceedings, amount to little emotional involvement. Even Wright Penn’s performance as the maltreated Surratt feels staid, if not one-dimensional given the opportunities for dramatic expression here. Each of the actors gives a fine performance: Danny Huston, Colm Meany, Evan Rachel Wood, and Justin Long all fill their roles nicely. McAvoy, Wilkinson, and Kline are particularly valuable onscreen for giving their roles more depth through the illusion of nuance. However, the storytelling is never as affecting as the historical potency of the event, and for many that may reduce the picture into a two-hour history lesson. But what a fascinating lesson.

Of course, even the most noble-minded historical retelling is bound to include some omissions, such as details about Aiken that make his heroic presence in Redford’s film suspect. You wouldn’t guess by The Conspirator that Aiken had questionable allegiances prior to the war, or that after the Surratt case, he appeared as a defendant himself in a check fraud case. Nevertheless, Solomon lends his script impressive historical detail with jealous attention to the injustices of Surratt’s trial, while Redford and cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel create a muddy visual presentation that bypasses the usual sheen of a period piece. Seemingly covered with filth and perspiration, Redford’s frame makes light a tangible thing through thick smoke and dusty courtrooms, the production successfully transporting us to another place and time.

Yet, the alternate place and time of the film might be the months and years following 9/11, when Stanton-esque figures Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld take over for the weak-minded President in a time of national crisis. Instead of finding the real culprit (Surratt’s son John is a stand-in for Osama Bin Laden), they invent one to satisfy what they consider to be a bloodthirsty mob banging at their door. Both tales end with Surratt and Saddam Hussein with nooses around their necks. Redford’s evident disgust with the post-9/11 actions of the US finds more salient arguments in The Conspirator than in his last effort, the soapboxing lecture-of-a-movie Lions for Lambs. Instead of sermonizing, he finds a moment in America’s history that helps raise questions about the government’s pattern of behavior and makes sure we’ll be able to identify such unconstitutional acts in the future.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review