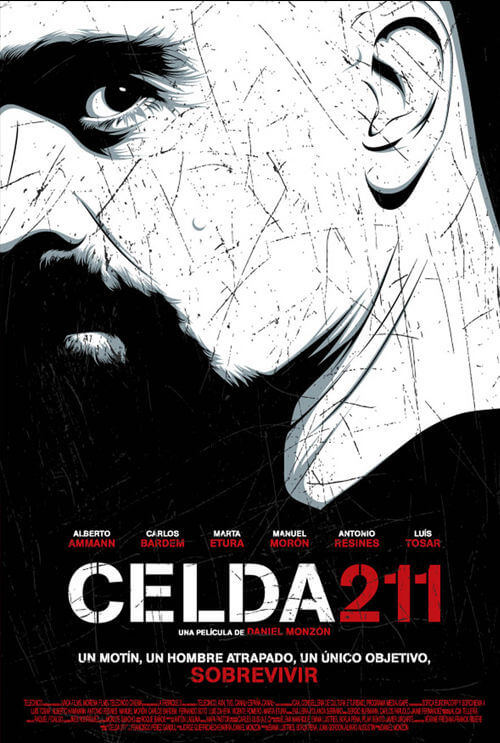

Cell 211

By Brian Eggert |

You have bad days, and then you have days like Juan Oliver’s first day at work. He’s been hired as a prison guard and, wanting to make a good impression, he decides to go in a day early for a tour. At home, his loving wife, Elena, is six months pregnant with their first child, and his new job will ease their financial tensions. On accident, he’s struck on the head by some debris falling from the prison’s crumbling walls; the guards temporarily place Juan in an empty cell while they call for help, but then a prison riot breaks out, so they leave him. Now Juan is alone with hundreds of enraged prisoners. He strips himself of conspicuous clothing and plays inmate, in constant fear of his true identity being discovered during the riot lockdown. After this, his day doesn’t get much better.

The Spanish film Cell 211 could have easily fallen into the trap of your standard prison break fare, filled with action and suspense, and predictable outcomes. But from the outset, the film surprises and engages us in unexpected ways, changing our perceptions of characters and the situation again and again, yet always in an emotionally prevailing way. The purpose seems to be a social commentary on Spanish prisons and their notably lax treatment of prisoners, but the script by writers Jorge Guerricaechevarría and the director Daniel Monzón, based on Francisco Pérez Gandul’s novel, never tells us how to feel about the issues. You either recognize the atrocities being shown or you don’t. For English-speaking audiences seeing this 2009 film stateside via import, the social commentary is even further distanced. And yet, as the drama plays out, the film affects us on an emotional level just as it would a viewer from Spain.

Young actor Alberto Ammann plays Juan, a thin, unexceptional character whose instincts serve him well. When discovered in Cell 211, the other prisoners take Juan to the riot’s mastermind, the unchallenged inmate ringleader Malamadre (Luis Tosar), a brutish short bald man with a menacing goatee and eyebrows ever pointing at his nose. Juan convinces Malamadre to play this riot smart; rather than destroy the prison cameras, leave one but cover it up, which lets the prison staff know who’s in control. As Malamadre’s trust for Juan grows, a negotiator attempts to secure the prisoners’ demands for better treatment, while also trying to find a reason to remove Juan from the situation without alerting the suspicions of the inmates. Meanwhile, Juan’s wife Elena (Marta Etura) learns about the riot and heads to the prison to see if Juan is involved; there, protesters and the media have formed a wall around the complex, and she’s caught in the middle.

The way this all plays out is flooring. Manzón focuses on the drama as it unfolds, giving precedence to Juan’s growing association with Malamadre and his constant thoughts of Elena. The prison staff sends misinformation to the media and to Elena about the situation, keeping everyone in the dark, which has some dire consequences. Through the course of the film, Manzón drops in brief scenes of Juan and Elena from that morning, showing us how delightfully in love they are, inferring how that love makes the worsening situation in the prison so tragic. Shooting with controlled digital cameras so that during manic riot scenes the image is shaky but decipherable, Manzón’s production is spare and devoid of style, much like the surrounding prison.

At the same time, the audience can’t help but consider the social consequences of Cell 211, as Spanish prisons are notoriously mismanaged, enough to become a major concern for the Spanish public. One begins to feel that Manzón sees the prison system as fully responsible for this debacle, as he ends his film by asking “Any questions?” This is after we spend the entire film asking ourselves how the prison staff could let this happen—after we see, in the first scene, an inmate commits suicide because he’s been neglected by the prison staff. In one respect, it’s reasonable to question sympathy for violent offenders, but in another respect, it’s basic human decency to care about the well-being of others, even prisoners. This film, in its own dramatic and suspenseful way, asks how you feel about it without projecting its own outlook onto the audience.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review