The Adventures of Baron Munchausen

By Brian Eggert |

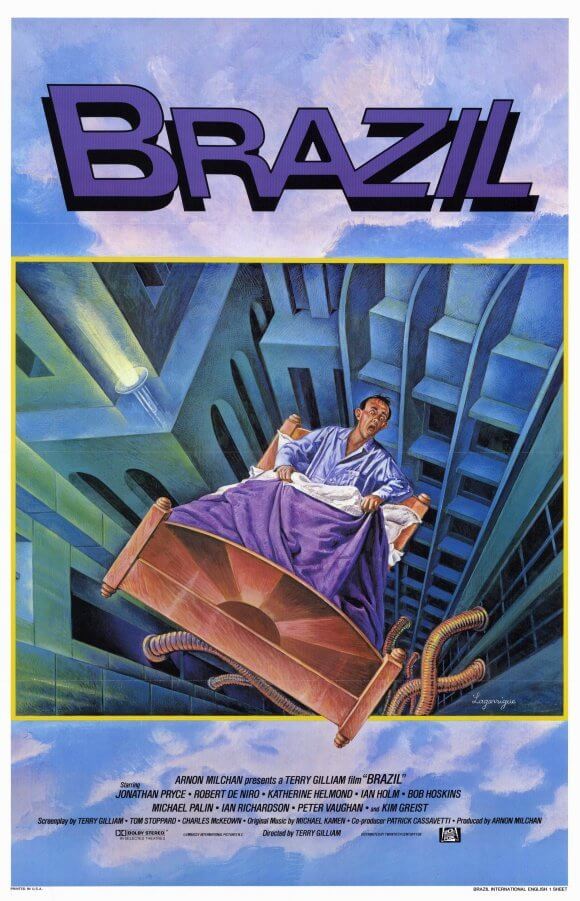

Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen is among the greatest of all fantasy films. Brought to life through the director’s layered sensory stimulation and visual luster, this filmic storybook follows the titular aged hero and a young girl gallivanting about in a series of tall tales, their journey returning adult viewers to their childhood and taking children on a fantastical escapade beyond their dreams. Full of boundless imagination, incredible special effects, and witty Monty Python-esque humor, the splendors of its movie magic are often overshadowed by the story of its over-budget, yearlong, and unthinkably catastrophic production, followed by a truncated and disastrous release in 1988. Yet, part of what makes the film so miraculous is how over the years, the stigma surrounding its behind-the-scenes troubles subsided to make way for an enduring experience. Much like the director’s best films, from Brazil to The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, by some wonder, an impossible work survived its tumultuous creation only to flop at the box office, and then slowly develop into a beloved fantasy classic.

Presented here are some of the broad strokes of Gilliam’s trials, but the production history is outlined to more exhaustive effect in Andrew Yule’s essential book, Losing the Light: Terry Gilliam & the Munchausen Saga. Yule’s behind-the-scenes log details the very worst of Hollywood politics both at the practical and executive level, while the film itself is yet another mirror metaphor in which Gilliam’s final product curiously reflects the film’s journey to the screen. It’s a backstory of stampeding elephants, big business posturing, salary scams, rights disputes, shady producers, poor filming conditions, and a torturous set of circumstances for its director and virtually all involved. When the studio wasn’t threatening to shut down production, the director was so incensed that he threatened to abandon the film altogether, famously punching a hole in the window of his own car in one such bout. The infamous financial disaster of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate has been called a “paradise” by contrast. Gilliam’s chaotic brand of filmmaking triumphed through seemingly unworkable circumstances nevertheless, maneuvering organizational and just-plain-bad-luck ruin—the extent of which only Gilliam could have perpetuated yet also somehow persevered through. As a result, the film itself remains sorely overlooked next to its production history.

The story goes that Gilliam visited George Harrison in 1979 and was shown the former Beatle’s original leather-bound copy of Rudolf Raspe’s The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen, thus implanting the seed of interest in Gilliam. The real Baron, born in 1720 to Hanoverian nobility, joined the Russian army in adulthood and fought the Ottomans. After his retirement, Munchausen became renowned for spinning elaborate and fantastical yarns about his wartime exploits, not because he was a pathological liar or some such fraud, but because his stories provided an acknowledged embrace of Big Fish tales—and a much-discussed amusement at dinner parties to boot. Raspe, a close friend of Munchausen’s, published his friend’s stories in 1785, just a few years before his own death. A half-century later, artist Gustave Doré cemented the fabled hero’s status with graphic, fabulous woodcuts. Munchausen has since become synonymous with lies and imagination, the latter quality greatly appealing to Gilliam. Having made Time Bandits (1981) and Brazil (1985), an adaptation of Munchausen’s tale would complete Gilliam’s unofficial “Dream Trilogy,” in which the downfalls of reality overwhelm and set apart his assorted dreamer protagonists.

The story goes that Gilliam visited George Harrison in 1979 and was shown the former Beatle’s original leather-bound copy of Rudolf Raspe’s The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen, thus implanting the seed of interest in Gilliam. The real Baron, born in 1720 to Hanoverian nobility, joined the Russian army in adulthood and fought the Ottomans. After his retirement, Munchausen became renowned for spinning elaborate and fantastical yarns about his wartime exploits, not because he was a pathological liar or some such fraud, but because his stories provided an acknowledged embrace of Big Fish tales—and a much-discussed amusement at dinner parties to boot. Raspe, a close friend of Munchausen’s, published his friend’s stories in 1785, just a few years before his own death. A half-century later, artist Gustave Doré cemented the fabled hero’s status with graphic, fabulous woodcuts. Munchausen has since become synonymous with lies and imagination, the latter quality greatly appealing to Gilliam. Having made Time Bandits (1981) and Brazil (1985), an adaptation of Munchausen’s tale would complete Gilliam’s unofficial “Dream Trilogy,” in which the downfalls of reality overwhelm and set apart his assorted dreamer protagonists.

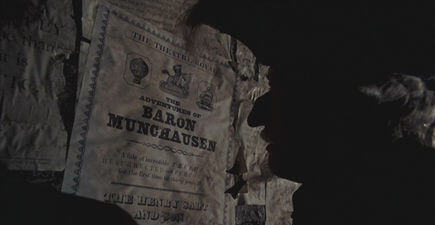

Gilliam, collaborating again with his Brazil co-writer Charles McKeown, opens his tale during the eighteenth century’s Age of Reason in an unnamed European town under siege by Turkish forces. Amid the battle’s gunfire and city’s ruins is a struggling theater in which The Henry Salt and Son production company stages their version of Munchausen’s tales. Owner Henry Salt (Bill Paterson) races to control his frenzied production, cannonballs, and explosions outside audible under the performances, though no one seems to notice. Backstage, Salt’s daughter Sally (Sarah Polley) scurries about, fretting the company’s name because she has no brother. A restless audience watches, among them “The Right Ordinary” Horatio Jackson (Jonathan Pryce), an elected official there to determine if Salt and Son’s company deserves a place in his modern city of rationality and logic. All at once, an elderly man (John Neville) in military garb enters from outside, declaring the play “Lies and rubbish!” as he climbs upon the stage, insisting he is the real Baron Munchausen, and that Salt’s play misrepresents his actual experiences. Munchausen resolves to tell the story as it really happened, beginning with how a wager between him and the Turkish Sultan (Peter Jeffrey) led to the current war.

At Munchausen’s wild explanation, in which he takes every last coin of the Sultan’s treasure after triumphing in a bet, logic-obsessed Horatio Jackson deems the theater must close its doors. Munchausen resolves to prove himself by stopping the war after he assembles his former comrades: Berthold (Eric Idle), the world’s fastest man; Albrecht (Winston Dennis), a massive strong man; Adolphus (Charles McKeown), an eagle-eyed sharpshooter; Gustavus (Jack Purvis), a dwarf with extraordinary hearing and the power to blow torrential gusts of wind. With Sally in tow, Munchausen lifts off above the town in a hot air balloon assembled from ladies’ undergarments and sets sail for a series of rescues and domestic encounters with mythical couples. First, they find Berthold on the Moon with The King of the Moon (Robin Williams, credited as Ray D. Tutto) and Queen Ariadne (Valentina Cortese), the Queen and the Baron sharing an evident romantic history. Albrecht, they find within a volcano attending the Roman god Vulcan (Oliver Reed) and his wife Venus (Uma Thurman) as their “dainty” man-servant. Adolphus and Gustavus believe themselves dead in the belly of a sea monster, but the Baron helps them escape with a modicum of snuff (most efficacious). All the while, Death pursues the Baron, with only Sally there to prevent the cloaked Grim Reaper from taking the Baron into the next life forever. Although his old age is revived by a touch of adventure, the Baron’s relevancy is his power, and the Age of Reason threatens to render Baron Munchausen irrelevant. Sally’s belief in his stories seems to be the only thing slowing Death’s pursuit.

At Munchausen’s wild explanation, in which he takes every last coin of the Sultan’s treasure after triumphing in a bet, logic-obsessed Horatio Jackson deems the theater must close its doors. Munchausen resolves to prove himself by stopping the war after he assembles his former comrades: Berthold (Eric Idle), the world’s fastest man; Albrecht (Winston Dennis), a massive strong man; Adolphus (Charles McKeown), an eagle-eyed sharpshooter; Gustavus (Jack Purvis), a dwarf with extraordinary hearing and the power to blow torrential gusts of wind. With Sally in tow, Munchausen lifts off above the town in a hot air balloon assembled from ladies’ undergarments and sets sail for a series of rescues and domestic encounters with mythical couples. First, they find Berthold on the Moon with The King of the Moon (Robin Williams, credited as Ray D. Tutto) and Queen Ariadne (Valentina Cortese), the Queen and the Baron sharing an evident romantic history. Albrecht, they find within a volcano attending the Roman god Vulcan (Oliver Reed) and his wife Venus (Uma Thurman) as their “dainty” man-servant. Adolphus and Gustavus believe themselves dead in the belly of a sea monster, but the Baron helps them escape with a modicum of snuff (most efficacious). All the while, Death pursues the Baron, with only Sally there to prevent the cloaked Grim Reaper from taking the Baron into the next life forever. Although his old age is revived by a touch of adventure, the Baron’s relevancy is his power, and the Age of Reason threatens to render Baron Munchausen irrelevant. Sally’s belief in his stories seems to be the only thing slowing Death’s pursuit.

Gilliam, too, would begin to wonder if his production could survive death, marking another link between a Terry Gilliam production and its screen story, much like Brazil. That film’s producer, Arnon Milchan, returned for Gilliam’s proposed Munchausen project in an executive capacity, establishing some initial interest at 20th Century Fox and Tri-Star Pictures. Milchan wanted to hire a show-runner producer and sought German-born Thomas Schuhly, a body-building ego who idolized Rambo. Several successful meetings between Milchan and Schuhly came to pass, but then Gilliam and his accountant Steve Abbott began to probe Milchan about several lingering questions about Brazil’s finances, and how Milchan was using unpaid monies from that project to launch The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. When these issues became too thorny for Milchan, he bowed out and left the production to Schuhly (whispers of resentment from the Jewish Milchan toward the German Schuhly abound). After, Gilliam and Abbott, along with partner Anne James, formed The Munchausen Partnership and joined Schuhly’s Rome-based Laura Films in a co-production, this despite Abbott’s research that pointed to Schuhly being a kind of Munchausen figure himself (Schuhly had exaggerated his credentials when he claimed to have worked on multiple films with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, but only a few of which could not be verified).

On Schuhly’s insistence, the production would be shot in Rome, where the producer believed it could be made for only $25 million; he assured costs were lower in Italy, whereas U.S. costs would have placed the budget upwards of $50 million. Columbia, then under CEO David Puttnam, agreed to supply $22.5 million of the proposed $25 million budget and gave Gilliam final cut, provisionally, provided a test audience of older and younger viewers (to match the Baron and Sally) scored the film well. This was a virtual impossibility, Gilliam’s most devoted fanbase being neither the very young nor very old. Nevertheless, Gilliam leaped headlong into production as debates over video and distribution rights ensued, and an agreement with completion guarantor Film Finances was struck. Film Finances would monitor the daily progress and budget, and, if needed, step in to assure completion. For Schuhly’s part, he secured a wonderful crew of Italian veterans, including production designer and frequent Pier Paolo Pasolini collaborator Dante Faretti; cinematographer Guiseppe Rotanno made several pictures for Luchino Visconti, including La Notti Bianche (1957) and The Leopard (1963); legendary actress Valentina Cortese (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965) would play dual roles as Queen Ariadne and the Salt Company actress Violet. Schuhly even promised his European connections could secure the film cameos by “friends” like Gérard Depardieu, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Marcello Mastroianni.

On Schuhly’s insistence, the production would be shot in Rome, where the producer believed it could be made for only $25 million; he assured costs were lower in Italy, whereas U.S. costs would have placed the budget upwards of $50 million. Columbia, then under CEO David Puttnam, agreed to supply $22.5 million of the proposed $25 million budget and gave Gilliam final cut, provisionally, provided a test audience of older and younger viewers (to match the Baron and Sally) scored the film well. This was a virtual impossibility, Gilliam’s most devoted fanbase being neither the very young nor very old. Nevertheless, Gilliam leaped headlong into production as debates over video and distribution rights ensued, and an agreement with completion guarantor Film Finances was struck. Film Finances would monitor the daily progress and budget, and, if needed, step in to assure completion. For Schuhly’s part, he secured a wonderful crew of Italian veterans, including production designer and frequent Pier Paolo Pasolini collaborator Dante Faretti; cinematographer Guiseppe Rotanno made several pictures for Luchino Visconti, including La Notti Bianche (1957) and The Leopard (1963); legendary actress Valentina Cortese (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965) would play dual roles as Queen Ariadne and the Salt Company actress Violet. Schuhly even promised his European connections could secure the film cameos by “friends” like Gérard Depardieu, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Marcello Mastroianni.

On the set, Gilliam quickly found himself in a situation where being an English-speaking director over an Italian-speaking crew left him little control. Moreover, the Italian crews worked slowly and progressed little in the time allotted for pre-production; they also engaged in a number of salary scams by overcharging for simple tasks, whereas Abbott learned that studios in London would have charged a fraction of the cost, and what’s more, they wouldn’t have had to work through a language barrier. Just after sets and miniatures were built, the production was already $4 million over budget. At the same time, Schuhly’s true colors began to show. Whenever a crisis emerged, he was nowhere to be found, regardless of his later insistence that he was always on set. Schuhly’s never-ending stream of broken promises began to accumulate into a pattern, while the concerned studio heads at Columbia Tri-Star, who had been sold to Sony in the meantime, wanted nothing to do with former CEO David Puttnam’s existing projects. Both Film Finances and the new Columbia demanded mandatory script cuts to make the budget, or at least make it more manageable. These cuts eliminated a number of key sequences, including a human chess match (think Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone) between the Baron and the Sultan, later replaced with the (cheaper) Sultan’s musical, “The Torturer’s Apprentice” with lyrics by Eric Idle and composer Michael Kamen. The entire moon sequence was cut down, and the King character, originally slated for Sean Connery, was abbreviated and instead played by Robin Williams, who demanded to appear under a pseudonym as he took the job as a favor to Gilliam. All the while, weather conditions were brutally hot shooting in Italy and Almeria in Spain. With special FX explosions going off and the disgruntled Italian crew frequently sabotaging the set-pieces, the conditions were dangerous besides. Polley recalls the experience as being “traumatic.”

Gilliam’s team would later agree: the production was not necessarily over budget; Schuhly had just approved an incorrect budget. In more than one instance, production was shut down altogether; Columbia even fired the whole crew at one point to reassess the budget. During this time, Neville—a renowned stage actor working his third season as Artistic Director at Stratford Festival Theater in Ontario, then directing Othello—was forced to wait in Italy, having no stop clause in his contract. Everyone else received a much-needed break. When production eventually resumed, Gilliam and McKeown had made several major compromises to get running again. In a rare act of sensibility, Schuhly and Columbia allowed post-production to shoot models and certain effects in Pinewood Studios in England. These shots wrapped effortlessly and without undue delay. After barely getting out of Italy with the completed film negative due to authorities questioning the production’s upwards of $5 million in unpaid bills (all found on Schuhly’s desk), Columbia execs refused to even screen the completed footage; they were preoccupied with the distended budget (final cost: over $41 million) and poor test scores.

Gilliam’s team would later agree: the production was not necessarily over budget; Schuhly had just approved an incorrect budget. In more than one instance, production was shut down altogether; Columbia even fired the whole crew at one point to reassess the budget. During this time, Neville—a renowned stage actor working his third season as Artistic Director at Stratford Festival Theater in Ontario, then directing Othello—was forced to wait in Italy, having no stop clause in his contract. Everyone else received a much-needed break. When production eventually resumed, Gilliam and McKeown had made several major compromises to get running again. In a rare act of sensibility, Schuhly and Columbia allowed post-production to shoot models and certain effects in Pinewood Studios in England. These shots wrapped effortlessly and without undue delay. After barely getting out of Italy with the completed film negative due to authorities questioning the production’s upwards of $5 million in unpaid bills (all found on Schuhly’s desk), Columbia execs refused to even screen the completed footage; they were preoccupied with the distended budget (final cost: over $41 million) and poor test scores.

New Columbia head Dawn Steel had no interest in promoting or putting any effort into the finished project beyond the very minimum necessary to recoup their investment. As a result, Columbia’s promotional campaign was nil, and, along with reports of the inflated budget and out-of-control production, critics responded by reviewing the budget more than the film. Even so, a vast majority (including Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss) saw a busy genius in Gilliam’s work, with only a few detractors to speak of (like the Newark Star Ledger critic Richard Freeman, who, believe it or not, wrote of the film’s lack of “common sense”). Columbia opened The Adventures of Baron Munchausen in a mere 46 theaters, where it did well for its per-theater average sales, numbers that typically would incite a studio to hasten a wider release the coming weekend. But after another four weeks, the film had expanded to only 92 theaters around the states. Other Columbia Tri-Star releases from that year averaged around 900 prints. The Adventures of Baron Munchausen received a smaller release than most independent productions, all due to a level of spite from Columbia execs toward Gilliam and his problem-ridden production. Even on its limited screens, the film made $8 million, and later earned four BAFTA and Oscar nominations each for technical awards; it won three BAFTA awards for costumes, makeup, and production design.

Watching the film today, never once does it look or feel like the result of a troubled production. Visually, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen dazzles. A common remark in the initial critical assessments was that, though the budget may have been swollen, every dollar is evident onscreen, not a dime ill spent. How joyously true. Gilliam’s exuberant production is one of elaborate sets, rich in detail, ornamented with colors and facets that busy the eyes and ignite the imagination. Each sequence in any of the film’s locations contains multifarious stimuli loaded onto the screen, filling us with wonder. The Sultan’s harem, for example, is populated by overweight and lace-draped concubines wading in a pool or lounging naked in a hammock hung between two columns; dwarves and children run about as the Sultan begins his recital of “The Torturer’s Apprentice,” and behind him, an executioner prepares Baron for a summary beheading. Or look at the chamber of Venus on the half-shell; Gilliam and Faretti breathe gorgeous life into Botticelli in their Renaissance ballroom of waterfalls and cherubs. Even the Moon sequence, which Gilliam and McKeown were forced to alter from a population of thousands to just two, the King and Queen, boasts a desert ocean, a charming one-dimensional city cutout, and star constellations swimming in the background’s black of space.

Watching the film today, never once does it look or feel like the result of a troubled production. Visually, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen dazzles. A common remark in the initial critical assessments was that, though the budget may have been swollen, every dollar is evident onscreen, not a dime ill spent. How joyously true. Gilliam’s exuberant production is one of elaborate sets, rich in detail, ornamented with colors and facets that busy the eyes and ignite the imagination. Each sequence in any of the film’s locations contains multifarious stimuli loaded onto the screen, filling us with wonder. The Sultan’s harem, for example, is populated by overweight and lace-draped concubines wading in a pool or lounging naked in a hammock hung between two columns; dwarves and children run about as the Sultan begins his recital of “The Torturer’s Apprentice,” and behind him, an executioner prepares Baron for a summary beheading. Or look at the chamber of Venus on the half-shell; Gilliam and Faretti breathe gorgeous life into Botticelli in their Renaissance ballroom of waterfalls and cherubs. Even the Moon sequence, which Gilliam and McKeown were forced to alter from a population of thousands to just two, the King and Queen, boasts a desert ocean, a charming one-dimensional city cutout, and star constellations swimming in the background’s black of space.

Gilliam orchestrates a convergence of cinematic, historical, artistic, and mythological references spanning countless cultures and epochs, all to celebrate the tradition of storytelling from the ancient Romans to Hieronymus Bosch to Marcel Carné. In a conscious nod to the theatrical metaphors perpetuated in Children of Paradise (1945), Gilliam opens his film on a stage and returns there in the finale, suggesting we’ve never left—that The Henry Salt and Son company has been swept away by Munchausen’s tales just as we have. How easily an audience loses themselves in the Baron’s stories, where not one moment is dull, and every last shot Gilliam has assembled contains some clever gag or striking image or incredible flourish. Beyond the strains of Monty Python DNA in its humor and the bountifully illustrated storybook quality, Gilliam rejuvenates the innocence and freedoms inherent to the imagination. Much like the reflective fiction and reality of Brazil’s making, this production and film are both about lies and reality, about a solitary dreamer trying to inspire cold authoritarians into believing that imagination can arouse a sense of wonder if you think it can. Munchausen triumphed over the nonbelievers in the film and inspired many with his magnificent stories, while, though Gilliam lost his battle, the enduring legacy of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen has lasted far longer than any of those who opposed or hindered its production.

Most endearing about the film is the romanticism of Gilliam’s longstanding call for imagination. His entire picture maintains that, without fantasy and escape, the world is a very dull and mechanized and over-regimented place. Each film in Gilliam’s “Dream Trilogy” contains this message in one form or another, although with varying consequences for the dreamer. In Time Bandits, the boy hero is left parentless and all but abandoned, with only his imagination to comfort him, free though he may be. Brazil leaves protagonist Sam Lowry defeated by the prevailing bureaucracies, locked inside the freedom of his head while his body is doomed to some unspeakable punishment by his dystopian authority. As for Baron Munchausen, he may have been assassinated by Horatio Jackson, and Death may have claimed his soul (clear metaphors for the studio and Schuhly), but the storyteller’s spirit carries on in the imagination of Sally and those touched by his stories. Consequently, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen remains Gilliam’s most hopeful entry in his unofficial triptych, ironically so, given it was the most creatively hampered of the three. Yet, at the same time, it is a film inspired by imagination to such a degree that no hindrance could ever restrain its themes. Proof lies in the picture’s lasting ability to transport its audiences to faraway lands on fabulist adventures, and solidifies Gilliam’s film as a grand and timeless cinematic treasure.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review