The Definitives

The Bridge on the River Kwai

Essay by Brian Eggert |

On the surface, Sir David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai is a superb epic filled with themes of bravery, valor, and idealism, all set against a grandiose backdrop of powerful images captured by virtuoso camerawork. Beneath the Hollywood exterior, however, resides a daring picture that confronts as much as it entertains. It tells the story of men who refuse to accept defeat, and while striving for their own narrow definitions of honor, their demise in the film’s climactic finale illustrates the lunacy of war. Through the enormity of its human drama, the picture became an immediate and distinctive piece of cinema history, not only for its preeminent standing as a classic but for bringing international recognition to David Lean as a master filmmaker. It would become the first, and perhaps the greatest, of Lean’s signature late-career epics, in which he places involved relationships between a few complex characters within vistas of uncommon splendor.

Lean did not always make epics. He built his name in the modest film industry of postwar Britain, where he could savor his artistic freedom making small romantic pictures like Brief Encounter (1945) and Oliver Twist (1948). In England, he was considered a major player, whereas internationally, he was a minor filmmaker and certainly not seen as an auteur. From humble and strict Quaker beginnings, Lean broke into the industry in 1927 by way of a gopher position, fetching tea and delivering messages in a small British film studio. He moved up through the ranks until he became an editor, earning a reputation as a notorious yet efficient cutter. Serving as an editor on many high-profile British releases, including Anthony Asquith’s Pygmalion (1938) and Powell and Pressburger’s ‘…one of our aircraft is missing’ (1942), he stepped into the director’s chair in 1942 on In Which We Serve, which gave way to several pointedly British releases. Still, from a worldwide perspective, Lean’s influence was confined to a British audience. By 1956, after more than a decade of experience and his most recent Oscar-nominated work on Summertime the year before, Lean was finally approached by Hollywood with a project seemingly designed to gather him international recognition.

Like Alfred Hitchcock before him, Lean’s talent would require a true Hollywood visionary to notice him and lure him overseas. Sam Spiegel had been an independent producer, mostly in France and Germany, until he fled a growing Nazi presence in Europe in 1933. Relocating to the United States, he quickly made a name for himself on profitable and bold releases, Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946) and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) among them. After shooting on location for John Huston’s The African Queen (1951), Spiegel’s reputation for authenticity was at its zenith. He approached Columbia Pictures’ boss Harry Cohn in hopes of adapting French author Pierre Boulle’s novel The Bridge on the River Kwai, another proposed location shoot, and received a green light. Fred Zinneman had turned down Spiegel’s offer to direct; likewise, Howard Hawks and John Ford rejected the material altogether. Despite his David O. Selznick-esque temperament, Cohn had also taken risks on audacious projects; he put his faith in Spiegel when the producer’s attention shifted to David Lean as director. When the offer was made to Lean, the director, who had never before worked with Spiegel, took the job on the advice of Katherine Hepburn, who had worked with Lean (on Summertime) and Spiegel (on The African Queen), and wryly believed the pairing would be a learning experience for both men.

Like Alfred Hitchcock before him, Lean’s talent would require a true Hollywood visionary to notice him and lure him overseas. Sam Spiegel had been an independent producer, mostly in France and Germany, until he fled a growing Nazi presence in Europe in 1933. Relocating to the United States, he quickly made a name for himself on profitable and bold releases, Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946) and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) among them. After shooting on location for John Huston’s The African Queen (1951), Spiegel’s reputation for authenticity was at its zenith. He approached Columbia Pictures’ boss Harry Cohn in hopes of adapting French author Pierre Boulle’s novel The Bridge on the River Kwai, another proposed location shoot, and received a green light. Fred Zinneman had turned down Spiegel’s offer to direct; likewise, Howard Hawks and John Ford rejected the material altogether. Despite his David O. Selznick-esque temperament, Cohn had also taken risks on audacious projects; he put his faith in Spiegel when the producer’s attention shifted to David Lean as director. When the offer was made to Lean, the director, who had never before worked with Spiegel, took the job on the advice of Katherine Hepburn, who had worked with Lean (on Summertime) and Spiegel (on The African Queen), and wryly believed the pairing would be a learning experience for both men.

Boulle’s book came from personal experience, having trained during World War II as a resistance fighter in Britain’s Force 136 and General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in Singapore. In the Far East, he learned about explosives, sabotage techniques, and how to blow bridges. When Japan overran Singapore in 1942, it forced Boulle’s group into Indochina, ruled by Vichy France. Boulle was soon captured and put into a POW camp; he escaped after two years. As he began writing a fictionalized account of his experiences after the war, he changed the story to a Japanese camp to shed light on the infamous “Death Railway,” a 300-mile long stretch of track from Burma to Thailand built between 1942 and 1943, whose construction took the lives of over 14,000 Allied soldiers. Given the cruelty of their overseers, prisoners could not help but almost collaborate with the Japanese simply to survive; yet, it was said that British Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey, the real-life figure on which Boulle based his protagonist, Colonel Nicholson, did no such collaborating. Col. Toosey’s men later took issue with Boulle’s suggestion when the author revealed the source of his inspiration. Like the film, the book earned much acclaim, but it lacked the natural and pointedly cinematic conclusion—something even Boulle himself would later admit.

The film begins with a rundown unit of British soldiers slogging toward a Japanese prison camp deep in Thailand’s jungles, led by their commander, Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness). As they arrive in Camp 16, Nicholson presumably orders a tighter appearance to convey the British army’s resilience, having them fall into lines and march, despite their condition. Lean resolved that the soldiers would whistle a pointedly British tune, one whose meaning is lost on American audiences. “The Colonel Bogey March” was written by Kenneth Alford in 1914. During the Second World War, British servicemen had devised their own bawdy lyrics for some good-spirited lampooning. The revised lyrics went: “Hitler has only one right ball/Goering has two, but they are small/Himler has something sim’lar/but Goebbels has no balls at all.” Whistling the melody was an easier solution than trying to pass the lyrics by any censor board. And while the scene itself has become one of the most iconic in all of cinema, few U.S. audiences grasp its humor, reading the march as a dignified demonstration versus a mocking protest. Composer Malcolm Arnold worked the tune into his score and earned an Oscar in the process.

When the British soldiers arrive in formation, the prison commandant, Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), announces they will construct a bridge over the River Kwai and that everyone will work. Nicholson reminds Saito that the Geneva Convention states no officer shall be subject to manual labor. Saito later confirms that even officers will be forced to work. When Nicholson refuses, Saito orders the enlisted men to work, then damns Nicholson and his officers to suffer under the tropical sun inside metal “punishment huts.” With the officers in captivity, progress on the bridge’s construction wanes. Saito has a strict deadline to complete the bridge, but his pride and honor refuse to permit Nicholson the minor victory. And Nicholson refuses to withdraw his legal precedent. The two men engage in a battle of wills, each driven by strict principles and personal codes of honor. Nicholson follows military law to the letter, whereas Saito adheres to a samurai’s bushido—both soldier’s codes. Both men consider the other man mad, and their mutual madness unfolds slowly over the course of the film.

Saito’s paranoia and desperation, coupled with severe pettiness, reveals his madness early on. When he orders the officers gunned down after they refuse to work, it takes the British medical officer, Major Clipton (James Donald), intervening before Saito changes his mind. Later, Saito eagerly watches through binoculars as Clipton appeals to Nicholson, but then he quickly returns to a casual sitting position when his quarters are approached, so as not to seem fraught. Saito must always appear in control, always composed; every decision must be his. Though, his attempts at false confidence are transparent. Saito tries to bribe a starved Nicholson out of his stance by offering “English corned beef” and cigars at his table, which just so happens to have two place settings. Eventually, Saito has no choice but to release Nicholson, if only so the officers will prompt their men to better their efforts. When he finally gives in to Nicholson’s demands, he makes an excuse to announce the release of the officers, who will not have to work, claiming he came to the decision as a tribute to the end of the Japanese-Russian war in 1905. In a major victory, Nicholson returns to his men, who cheer their commander and raise him up, while Saito weeps for his loss of face.

Both Saito and Nicholson are tragic, almost comic figures whose unyielding ways grow progressively skewed. Nicholson’s adherence to military law comes into question early in the film when he announces any escape plans, usually a soldier’s duty while in captivity, are to be canceled. He rationalizes that the British army in Singapore was ordered to surrender, thus making any escape attempt a possible breach of military law. After being detained in Saito’s “punishment hut,” Nicholson’s devotion to principle nearly proves fatal, and his decisive victory over Saito in the matter of principle seems to vindicate his adherence to military law even further. Released from the hut, Nicholson has gone mad with law, and Arnold’s music plays eerie, winding strings that reverberate the character’s spiraling madness. Nicholson begins with the orderliness of his men. He resolves to restore discipline among the ranks by concentrating their energies on a single goal: building the bridge over the River Kwai. Nicholson hopes the bridge will be a monument to British ingenuity, even as prisoners—a symbol that will outlast the war. His vision proposes an awareness of a bigger picture than the politics of war. Perhaps too big a picture. For the sake of lasting British pride, Nicholson sacrifices his compatriots; he forgets or simply ignores that his actions help the enemy. Meanwhile, Saito quietly accepts that the British officers will oversee the rebuilding of the bridge from scratch, as the Japanese engineer has demonstrated technical incompetence.

While Nicholson suffers the jungle heat in detainment, an American in Saito’s prison, Naval Commander Shears (William Holden), plans a getaway. Barely escaping the jungle alive, he finds rescue in a Siamese village and recovers from his ordeal in a Ceylon hospital, where he enjoys the peaceful beaches and the company of an affectionate nurse. While mending, Shears is approached by Major Warden (Jack Hawkins), of the shrewdly renamed Force 316, to accompany a commando mission back into the jungle, where they will sabotage the bridge over the River Kwai. Shears refuses until Warden reminds him that he is not Shears but an enlisted man that switched identities with the real Commander Shears to get better treatment after their ship sank. Now reactivated with the “simulated rank of Major” and under British control, “Shears” has no choice but to join. The commandos parachute into the jungle and, along with a Siamese guide and several porters, they make their way to the bridge.

While Nicholson suffers the jungle heat in detainment, an American in Saito’s prison, Naval Commander Shears (William Holden), plans a getaway. Barely escaping the jungle alive, he finds rescue in a Siamese village and recovers from his ordeal in a Ceylon hospital, where he enjoys the peaceful beaches and the company of an affectionate nurse. While mending, Shears is approached by Major Warden (Jack Hawkins), of the shrewdly renamed Force 316, to accompany a commando mission back into the jungle, where they will sabotage the bridge over the River Kwai. Shears refuses until Warden reminds him that he is not Shears but an enlisted man that switched identities with the real Commander Shears to get better treatment after their ship sank. Now reactivated with the “simulated rank of Major” and under British control, “Shears” has no choice but to join. The commandos parachute into the jungle and, along with a Siamese guide and several porters, they make their way to the bridge.

Warden makes the film’s third madman, driven by duty no matter the cost. After taking a bullet in the foot while saving his green comrade Lieutenant Joyce (Geoffrey Horne), Warden pushes himself to limp through the rough jungle terrain, continuously losing blood, to reach the location before the bridge’s first train arrives carrying Japanese soldiers and VIPs. Taking out both the train and the bridge together would make a “jolly good show,” and Warden refuses to miss the opportunity. Warden’s devotion to the target is another case of military madness, and Sheers does not hesitate to confront his self-destructive militarism: “With you, it’s just one thing or the other: destroy a bridge or destroy yourself. This is just a game, this war. You and Colonel Nicholson, you’re two of a kind. Crazy with courage. For what? How to die like a gentleman. How to die by the rules. When the only important thing is how to live like a human being.”

By this time, Nicholson has pushed his men to extremes to complete the bridge on time. It has become his obsession to erect this symbol of the British spirit; all other concerns are nonexistent. He even asks that some of the capable wounded and officers work alongside their men, despite his earlier victory over Saito on this very point. Only Clipton questions Nicholson’s intentions to no avail. As the bridge nears completion, the commandos covertly place charges about the structure in the night and intend to detonate with the inaugural train’s arrival the next day. In the morning, Nicholson makes a final inspection, and, as the water level on the river has dropped overnight, he sees the exposed wires of the explosives. Time is short as the Japanese train approaches in the distance. Nicholson calls Saito’s attention to the wires and, together, they follow them downriver to the detonator box. The commandos are spotted, inciting Japanese gunfire. Joyce kills Saito with his knife. Nicholson attacks Joyce in fear of his precious bridge being destroyed. Warden responds with mortars. Shears makes his way to Nicholson, who recognizes the American and realizes his own folly. “What have I done?” says Nicholson, who approaches the detonator, only to die from the impact of a mortar shell and fall on the plunger. When he falls, the bridge explodes, sending the train and the structure into the river. Surveying the bodies, Clipton observes with incredulous dread, “Madness! …Madness!” and encapsulates the entire film’s meaning.

Given his disconnection with reality up to this point, there’s some conjecture over Nicholson’s behavior in the finale. Did Nicholson fall on purpose? Or was it merely an accident that landed him on the plunger? Lean’s intentional ambiguity allows the viewer to assign their own meaning, and arguments have been made for and against Nicholson’s objective. Certainly, his last line of dialogue reinforces the argument that Nicholson deliberately fell on the plunger. On the other hand, if it occurred by accident, then his collapse gives the moment poignant, fatalistic meaning. The most likely solution is that Nicholson makes for the plunger to push it, then dies suddenly, and in death, he falls on the plunger. Lean cuts to the explosive detonator after Nicholson utters “What have I done?”—implying that the Colonel sees the plunger and then progresses toward it. Doubtless, had Warden’s mortar not exploded behind him, Nicholson would have depressed the plunger and flattened the bridge himself. And yet, not knowing for certain fails to provide the certainty that would otherwise grant Nicholson redemption, which in turn would diminish the potency of the film’s catastrophic ending.

Given his disconnection with reality up to this point, there’s some conjecture over Nicholson’s behavior in the finale. Did Nicholson fall on purpose? Or was it merely an accident that landed him on the plunger? Lean’s intentional ambiguity allows the viewer to assign their own meaning, and arguments have been made for and against Nicholson’s objective. Certainly, his last line of dialogue reinforces the argument that Nicholson deliberately fell on the plunger. On the other hand, if it occurred by accident, then his collapse gives the moment poignant, fatalistic meaning. The most likely solution is that Nicholson makes for the plunger to push it, then dies suddenly, and in death, he falls on the plunger. Lean cuts to the explosive detonator after Nicholson utters “What have I done?”—implying that the Colonel sees the plunger and then progresses toward it. Doubtless, had Warden’s mortar not exploded behind him, Nicholson would have depressed the plunger and flattened the bridge himself. And yet, not knowing for certain fails to provide the certainty that would otherwise grant Nicholson redemption, which in turn would diminish the potency of the film’s catastrophic ending.

Deciding upon an alternate finale where the bridge explodes was among the first changes made by the script’s initial writer. Boulle spoke almost no English, so Spiegel sought an experienced Hollywood scribe for the adaptation. Screenwriter Carl Foreman (High Noon) was hired in secret and would not receive screen credit due to Columbia’s policy of not employing blacklisted writers, but then his draft was not the version used. Foreman’s script lost the “spirit of the book,” according to Lean, as it opened with an absurd submarine rescue sequence and contained no end of actionized war-movie clichés. Then again, Foreman did have the insight to blow the bridge in the finale. Boulle’s ending offered no explosion; rather, Col. Nicholson saves his precious bridge. Forman realized that the bridge’s destruction further symbolized the insanity of the narrative’s conflict. Years later, Boulle agreed the film’s ending was superior. Among Foreman’s other changes to the novel, the character Major Shears, originally a British commando, became an American if only to satisfy U.S. audiences with a typical hero type.

To clarify what was desired from a screen story, Lean and associate producer Norman Spencer completed a treatment. Calder Willingham (co-writer of Paths of Glory) replaced Foreman at Lean’s request and would follow Lean and Spencer’s treatment. Lean believed Willingham would better grasp the story’s pronounced anti-war themes, given his credits, but Willingham proved to be what Lean called a “touchy” writer and left the production when Lean resisted some of his ideas. For a time, Lean worked on the script himself, while Spiegel enlisted another blacklisted writer, Michael Wilson, who would later adapt another Boulle novel, The Planet of the Apes. The final script materialized largely from Lean and Wilson’s efforts, and Lean would later become known for personally retooling every script that he filmed. Despite the collaborative efforts on the final screenplay, Spiegel enraged many by giving sole credit for the script to Boulle, who won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. As Boulle could not speak English, he accepted the Oscar, believing it was for his novel. He later learned the truth and condemned the decision. In 1984, the Academy corrected their decision and gave Foreman and Wilson posthumous Oscars; a restoration of The Bridge on the River Kwai in 2000 even placed Foreman and Wilson’s names in the opening credits. Lean’s contributions to the script were never recognized.

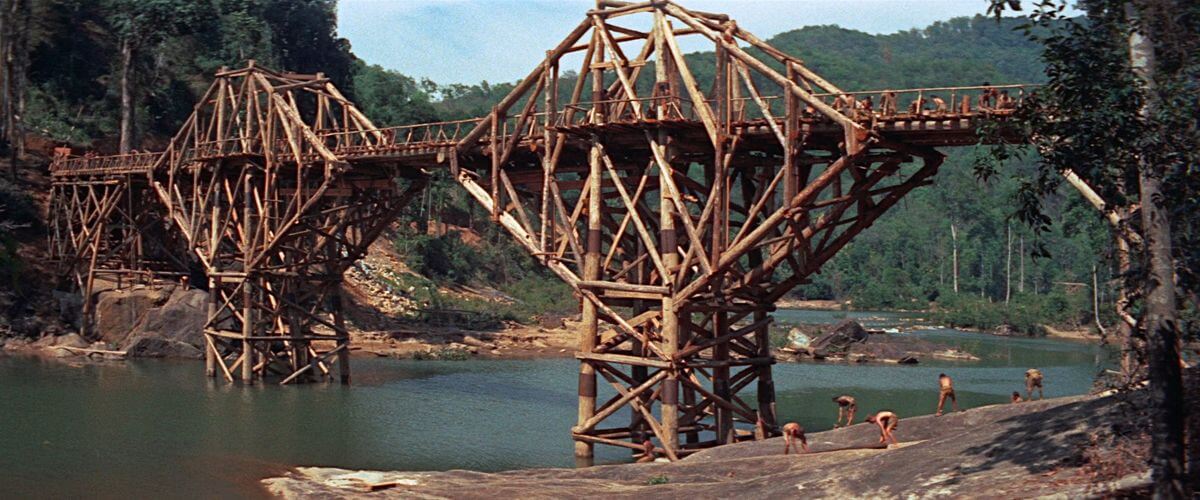

Preproduction began with plans to shoot in the jungles of Ceylon. While scouting locations, Lean and production designer Donald Ashton were approached by a local man who gave them a tattered bit of rice paper; on it was a sketch of a bridge on the Death Railway, which he had planned to pass to commandos for sabotage but never had the chance. Having smuggled the paper out of Burma during the war, he gave it to Lean and Ashton, and Ashton used it as his design for the bridge in the film. The shoot was set in a valley in the jungle; getting there meant transporting supplies for the film’s bridge across rough terrain, including a small river. Ashton and engineer Keith Best practiced constructing a bridge by building a lesser version over this river. The final bridge stood 425 feet long and 90 feet high and was built several months before filming began. It cost $52,000 to complete, a figure which Spiegel inflated to $250,000 in press interviews. The train that rolls across in the finale was 65-years-old and purchased from the Ceylonese government. In the final scene scheduled to shoot, both the bridge and train would be destroyed; amazingly, no miniatures were discussed. Such Hollywood trickery was never an option for Lean or Spiegel, the production’s other advocate for authenticity.

Preproduction began with plans to shoot in the jungles of Ceylon. While scouting locations, Lean and production designer Donald Ashton were approached by a local man who gave them a tattered bit of rice paper; on it was a sketch of a bridge on the Death Railway, which he had planned to pass to commandos for sabotage but never had the chance. Having smuggled the paper out of Burma during the war, he gave it to Lean and Ashton, and Ashton used it as his design for the bridge in the film. The shoot was set in a valley in the jungle; getting there meant transporting supplies for the film’s bridge across rough terrain, including a small river. Ashton and engineer Keith Best practiced constructing a bridge by building a lesser version over this river. The final bridge stood 425 feet long and 90 feet high and was built several months before filming began. It cost $52,000 to complete, a figure which Spiegel inflated to $250,000 in press interviews. The train that rolls across in the finale was 65-years-old and purchased from the Ceylonese government. In the final scene scheduled to shoot, both the bridge and train would be destroyed; amazingly, no miniatures were discussed. Such Hollywood trickery was never an option for Lean or Spiegel, the production’s other advocate for authenticity.

For the cast, Lean originally wanted Charles Laughton (Rembrandt) for Col. Nicholson, although this has been the source of many disputes. Laughton, who had worked with Lean on Hobson’s Choice in 1954, claimed the director sought him out for the role, whereas Lean insisted he never really wanted Laughton, realizing early on that the robust actor would look absurd leading a troupe of starved soldiers through the jungle. When Alec Guinness was approached, though Lean had worked with him a decade earlier on Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist, the actor had since been associated with comedies like The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955). Nevertheless, Guinness passed on the draft he had read, it being an earlier version penned by Foreman. Guinness took much convincing from Lean and the latest draft before he would accept the role.

Lean’s one misstep in his direction was attempting to make Guinness perform the role contrary to the actor’s instincts. Guinness communicates through subtlety, offering audiences an irresistible curiosity in his characters; they are defined through their internal mechanisms versus external behavior. On the outside, Nicholson appears sensible and logical; he is composed and distinguished, even when tested physically. On the interior, however, is madness. Guinness’ characters often share this quality of internalization, forcing audiences to consider how his characters’ minds work. Lean attempted to bring Guinness to the occasional emotional outburst to depict the camaraderie between Nicholson and his men, or Nicholson’s irritation with Saito, but Guinness refused, and his stubbornness caused many an argument. Guinness played the role with unswerving control toward both his men and the Japanese, and yet, despite this control, in a stroke of genius irony, Nicholson does not consider the impact of his complicity in Saito’s plans. A calm statement of “What have I done?” in the climax implies a sudden realization but does not shatter the character’s impenetrability, rather adds an enigmatic quality to a seemingly straightforward finale. His performance would earn him his first Oscar.

For Major Shears, William Holden was the first and only choice for Lean, though Cary Grant had been considered. At the height of his celebrity, the charismatic Holden earned his paycheck thanks to his popularity, although his talent was often overlooked in favor of his good looks. But the actor behind Sunset Blvd. (1950) and Stalag 17 (1953) deserved every cent of his then-unprecedented paycheck of $300 thousand and ten percent of the box office receipts. Silent film star Sessue Hayakawa was chosen as Nicholson’s political rival yet stubborn spiritual equal, Col. Saito. Lean later believed the Japanese actor had become somewhat senile, having lost much of his English since his acting prime in the Silent Era. As a result, he spoke his lines phonetically and read only the pages of the script where his character had dialogue. When Saito’s death scene was to be filmed, Hayakawa stood motionless, unaware his character was supposed to die because his character had no lines in the scene.

For Major Shears, William Holden was the first and only choice for Lean, though Cary Grant had been considered. At the height of his celebrity, the charismatic Holden earned his paycheck thanks to his popularity, although his talent was often overlooked in favor of his good looks. But the actor behind Sunset Blvd. (1950) and Stalag 17 (1953) deserved every cent of his then-unprecedented paycheck of $300 thousand and ten percent of the box office receipts. Silent film star Sessue Hayakawa was chosen as Nicholson’s political rival yet stubborn spiritual equal, Col. Saito. Lean later believed the Japanese actor had become somewhat senile, having lost much of his English since his acting prime in the Silent Era. As a result, he spoke his lines phonetically and read only the pages of the script where his character had dialogue. When Saito’s death scene was to be filmed, Hayakawa stood motionless, unaware his character was supposed to die because his character had no lines in the scene.

Shooting commenced in November 1956 and lasted until May of the next year. In all, 251 days were spent in the jungle, in a valley where winds were infrequent, and the torturous heat meant occasional dips in the nearby river. Lean’s obsessive perfectionism incensed his cast and crew in this environment. They balked at the sometimes over-ponderous approach of their director; he brooded over individual shots, much to their annoyance, and worked out his directorial dilemmas while looking upon the bridge, sometimes for hours. Not only was it Lean’s first time using CinemaScope, it was his first Hollywood picture, and an epic one at that. Pressure from Spiegel only worsened matters, and Lean became aggravated whenever the producer was on set. Spiegel spoke to Lean when the production went considerably over-budget, costing $800 thousand more than planned. But Lean had no concern for budgets or shooting schedules; he cared only about getting the perfect shot and resolved that no one remembers the broken budget or over-schedule shoot after the film becomes a hit. Spiegel was not so confident. The combination of squalid environmental conditions, an increasingly testy crew that later led a union strike, and Lean’s determination to get the perfect shot manufactured a nightmare production. By the time shooting was over, most of the cast and crew had been stricken with some kind of illness, most commonly dysentery.

Watching from an air-conditioned limo, Spiegel looked on as Lean and company prepared the final shot: the bridge’s destruction. Explosive experts from Britain’s Imperial Chemical Industries oversaw the blast. The bridge’s eventual obliteration was not merely a special effect but a controlled demolition. Five cameramen were to begin rolling their CinemaScope cameras, press a button to indicate they had done so, and then retreat to the safety of a bunker that would shield them from debris sent flying in the explosion. A stuntman acting as train operator would leap from the locomotive just before the train reached the bridge. And Lean would press the button to detonate the explosives. When it came time to film the scene, the moment’s excitement caused one cameraman to forget about pressing his button. Fearing the cameraman was not in his bunker, Lean could not trigger the explosion. This false start caused the train to derail off the track, requiring 15 men and several elephants to help get it back into position. The shot was completed the next day, and all went smoothly. As principal photography had been completed, Spiegel announced that Cohn wanted the production to wrap; the cast and the majority of the crew went home. Upon Lean’s insistence, he and a skeleton crew were allowed to stay behind to capture some establishing shots, such as the opening and closing hawk images, which underscore the film’s themes.

All of Lean’s perfectionism on the set was subject to his ruthlessness as an editor. He and editor Peter Taylor, with whom Lean had worked on Summertime, delivered a cut that ran 161 minutes. Spiegel believed too much was cut, whereas Columbia executives like Cohn thought it ran too long. Nevertheless, both critics and audiences approved, making the film an international blockbuster that earned $22 million at the box office. However, many viewers confused The Bridge on the River Kwai as a British production, given its subject, the British director, and mostly British actors. But Spiegel was an independent Hollywood producer whose production was distributed and paid for by a principal Hollywood studio. The truth is, the meager British film industry of the time could never have handled a production of this magnitude. Only in Hollywood could a story of this size be told, and only Lean could give it such depth.

All of Lean’s perfectionism on the set was subject to his ruthlessness as an editor. He and editor Peter Taylor, with whom Lean had worked on Summertime, delivered a cut that ran 161 minutes. Spiegel believed too much was cut, whereas Columbia executives like Cohn thought it ran too long. Nevertheless, both critics and audiences approved, making the film an international blockbuster that earned $22 million at the box office. However, many viewers confused The Bridge on the River Kwai as a British production, given its subject, the British director, and mostly British actors. But Spiegel was an independent Hollywood producer whose production was distributed and paid for by a principal Hollywood studio. The truth is, the meager British film industry of the time could never have handled a production of this magnitude. Only in Hollywood could a story of this size be told, and only Lean could give it such depth.

In addition to Lean’s much deserved Oscar for Best Direction, cinematographer Jack Hilyard, editor Peter Taylor, and composer Arnold also took home Oscars. Along with the aforementioned win for Guinness and the writers, that made seven statues in all. His talents proven, Lean’s success earned him job offers abound for all manner of epics. MGM offered him their Mutiny on the Bounty remake; Universal offered Spartacus; William Wyler even asked Lean to shoot the chariot race sequence in Ben-Hur, promising the director a separate screen credit for that sequence alone. Generous as these offers may have been, Lean, following his love of India, instead turned toward a biography of Mahatma Gandhi that crumbled after some development. In time, Spiegel suggested another historical epic, this one about T. E. Lawrence, the English officer who organized the Arab uprising against the Turks in World War I. That project would become Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Lean’s most successful and arguably his most popular film, which he followed with other successful historical epics like Doctor Zhivago (1965) and Passage to India (1985).

Beginning with The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lean’s creation of what Martin Scorsese has called “the intelligent epic,” along with his reputation as a god-like and visionary presence on set, has solidified the director’s legacy. His influence has spread to uncountable directors who have paid homage to his work. Steven Spielberg has acknowledged that he shot Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) in Sri Lanka, near where Lean shot The Bridge on the River Kwai, if only to walk in Lean’s cinematic footsteps (Spielberg’s film even contains a visual tribute when thousands of giant fruit bats fill the sky, mirroring a scene in The Bridge on the River Kwai). Anthony Minghella’s extensive humanist epics, such as The English Patient (1996) and The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), have closely followed Lean’s model. And Hollywood could not have filmmakers like Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, and Ridley Scott without Lean’s interest in psychological complexity and visual bravado.

Yet, for all its size and brilliance and influence, it remains curious that The Bridge on the River Kwai did so well. Neither a typical crowd-pleaser nor an effortless piece of popcorn entertainment, the film’s themes of madness and fate contain severity that demands a refined audience. The film defies the suggestion that adventure cannot exist in a story fixed by antiwar ideals, as Lean reduces the story’s immensity to a few individuals instead of shallow battles or numbing shootouts. The finale’s explosion is less a cathartic evocation of violence than a symbolic representation of the characters’ burgeoning madness, which Clipton points out with such disbelief in his final summary of the film’s events. Lean’s power to infuse these themes with striking imagery and skilled storytelling are what set his epics apart, earning them comparisons to great novels and Shakespearian tragedy.

The imposing size of David Lean’s films often leads to doubts that a single man could be responsible for such ambitious stories. But Lean’s personal touch, his defining characteristic as an auteur director, resides in his skill for bringing the human question into stories otherwise defined by their majestic scenery and narrative magnitude. As much as his epic pictures are about the visual scope, they are about grand personal conflicts intensified by the setting. His characters, such as Colonel Nicholson, or later T. E. Lawrence and Dr. Yuri Zhivago, resist precise and typical hero classifications, demanding that an audience consider the narrative’s deeper psychological makeup while also enjoying the sweeping size of Lean’s presentation. His ability to fashion sophisticated yet universally entertaining motion pictures like The Bridge on the River Kwai grows from his control as an artist and craftsman whose place belongs among the greatest of all directors.

Bibliography:

Anderegg, Michael. David Lean. Twayne, 1984.

Boulle, Pierre. The Bridge on the River Kwai. Translated by Xan Fielding. Time, 1964.

Brownlow, Kevin. David Lean: A Biography. St. Martin’s, 1997.

Maxford, Howard. David Lean. Batsford, 2000.

O’Connor, Garry. Alec Guinness: Master of Disguise. Hodder & Stoughton, 1994.

Phillips, Gene. Beyond the Epic: The Life & Films of David Lean.The University of Kentucky Press, 2006.

Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of David Lean. Barnes, 1974.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review