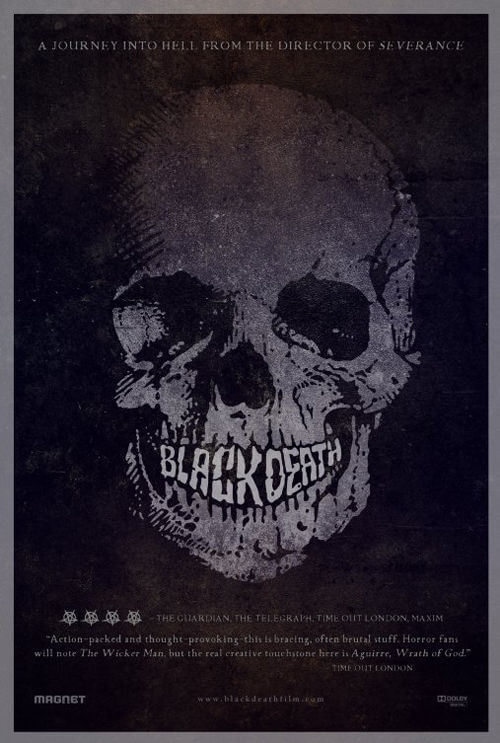

Black Death

By Brian Eggert |

Earlier this year, the low-rent medieval horror tale Season of the Witch opened and featured Nicolas Cage as a knight journeying through dark forests and cursed terrain to an ominous village; once there, his protagonist found the root of evil and the answers to his questions of faith. Filled with bad special effects, shoddy direction, and acting so hammy it could be served Easter Sunday, that B-grade farce barely worthy of the SyFy Channel nevertheless held possibility in its basic concept. And thanks to director Christopher Smith and screenwriter Dario Poloni, the same basic idea is realized to weighty, grim degrees in Black Death, a modest period drama with enough bloody thrills to entice mainstream audiences, and enough meditative notions on religion to satisfy more sophisticated viewers.

Fog machines are on overdrive to create this film’s barren, disease-ridden, corpse-laden landscape set in 1348, at the height of Europe’s suffering under the Bubonic Plague. More than a third of the population was lost to the disease, yet Poloni’s meticulously researched script was correct when suggesting those who survived during plague times were accused of godlessness. The story begins when a young monk, Osmund (Eddie Redmayne), hopes to escape his dying village, and his duties to God, to the forest with his secret lover, Averill (Kimberley Nixon). He prays for a way out and soon enough a knight, Ulric (Sean Bean), answering Osmund’s prayers, rides into the village in search of a faithful guide. On a mission from their Bishop, envoy Ulric and his small gang of holy mercenaries follow Osmund and find a village that has gone untouched by the surrounding pestilence.

Believing the secluded villagers must be in league with Satan to have avoided the plague (which is thought to be the wrath of God), Ulric plans to find their leader, an alleged necromancer capable of bringing the dead back to life, and return with him for judgment. When they arrive at the isolated village surrounded by thick marshlands, the heroes find a thriving, healthy community wary of outsiders and led by (gulp) a woman. The blonde-haired Langiva (Carice van Houten, from Black Book) shows signs of being a witch (her talents with herbs, for example), but something else is off about the shifty-eyed villagers. Sure enough, Ulric, Osmund, and crew find their faith tested in the face of temptation and demonstrate the limits to how far one will open their arms in service of their god.

This is the fourth film by British genre director Smith—preceded by Triangle (2009), Severance (2006), and Creep (2004)—and by far the best of the lot. It’s smart, exciting, and best of all, insightful. The action sequences are realistic and make sublime use of the production’s low budget, whereas the makeup effects used to render oozing pustules and boils never fail to create an appropriate yuck response. Comparisons will no doubt be made to Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man, as the similarly structured stories imply the dangers of blind faith and dogmatic devotion. Smith also points out the hypocrisy of a religion that calls for mercy yet uses cruelty to exact its power, and, through the example of witchcraft, addresses that other religions are no better, as they often resort to the same vindictive methods employed by Christianity. In the end, through a poignant and horrifying epilogue, the enemy proves to be those who choose to believe whatever they must in order to preserve their beliefs.

Much like Season of the Witch, Smith’s film was delayed a number of times despite its completion years ago. Perhaps the distributors didn’t want to contend with their Nic Cage competition, or perhaps the subject matter was just too grim to market—films about the Dark Ages have never been blockbuster material. So after an underwhelming performance at the British box office last year, Black Death earned a video-on-demand premiere and limited theatrical release a month later stateside. Surely this will be one discovered on home video and spread via word-of-mouth among a very limited crowd. But as it grows upon reflection and with serious consideration, the film is not easily forgotten. For those willing to stomach harsh realism from a gloomy period in history and confronting notions on religion, Smith has delivered a rewarding film surprisingly bereft of the typical downfalls usually present when mixing horror and history.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review