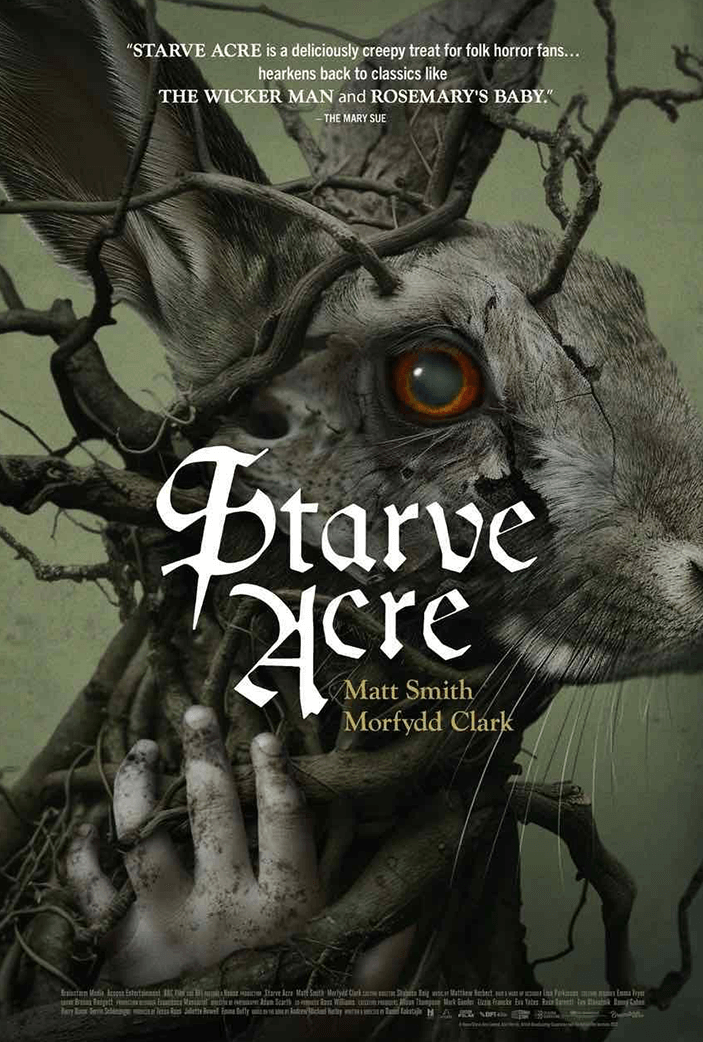

Starve Acre

By Brian Eggert |

Note: Although released last fall in the UK, Starve Acre arrives in limited release to US theaters on July 26, 2024, courtesy of Brainstorm Media.

After his 2017 debut feature, Apostasy—which draws from his upbringing in a strict and isolated Jehovah’s Witness community—writer-director Daniel Kokotajlo delves into similar themes in Starve Acre. Based on the 2019 novel by Andrew Michael Hurley, the film involves an obsessive devotion to a religious doctrine as well. However, instead of a Christian sect, the filmmaker explores British folklore in service of a moody horror story steeped in an obscure myth. An opening poem attributed to Neil Willoughby tells of a figure named Dandelion Jack, though Hurley invented the figure for this story. Backed by cultish followers determined to make sacrifices that will facilitate a return of this “phantom” of the natural world, Dandelion Jack is the gimmicky specter behind an otherwise slow-burning narrative that unfolds like a chamber drama. Limited to a few locations, mostly around an isolated country house on the outskirts of 1970s Yorkshire, the unnerving Starve Acre relies on terrific performances. The quiet intensity of Matt Smith and Morfydd Clark sell this familiar but creepily effective tale of grief manifesting as something scary.

Rigidly adhering to the precepts of the folk horror subgenre, whose resurgence in recent years has resulted in a mixed bag of new entries—from the highs of Midsommar (2019) to the lows of Children of the Corn (2023)—Kokotajlo provides a textbook case with Starve Acre. A rural setting where city folk feel like outsiders in the tight-knit and superstitious community? Check. A local pagan mythology rooted, quite literally, in the power of Nature? Check. A symbolic use of seasonal transitions and cycles? Check. A dark past buried and then unearthed—again, quite literally? Check. A séance that calls upon a pagan god? Check. Personal trauma that finds a healing outlet through the twisted rebirth imagery of the grim local legend? Check. However, noting these standard folk horror themes is not to disparage Kokotajlo for deploying them in his movie; rather, it’s to note their presence and admire how well the filmmaker weaves them into his portrait of a troubled marriage.

Smith plays Richard, an archeology instructor who moves his family back to his childhood home on the titular land. Although his upbringing involved his father—author of the Dandelion Jack poem—performing a series of disturbing, ritualistic abuses on him, Richard returns with his wife Juliette (Clark) and young son Owen (Arthur Shaw), hoping to reclaim some aspect of his warped childhood by creating new and better memories. But that ambition goes sour after Owen’s recent disturbing outbursts, reminiscent of the behaviors in Peter Shaffer’s play Equus. Owen also claims to hear whispers from someone named Jack Grey. Richard worries that a local handyman, Gordon (Sean Gilder), once a friend of his late father’s, may have filled Owen’s head with his father’s ideas about a spirit-like personification of Nature. And once a tragedy befalls the family, supernatural rumblings surround them, destabilize the marriage, and introduce a macabre element into the house.

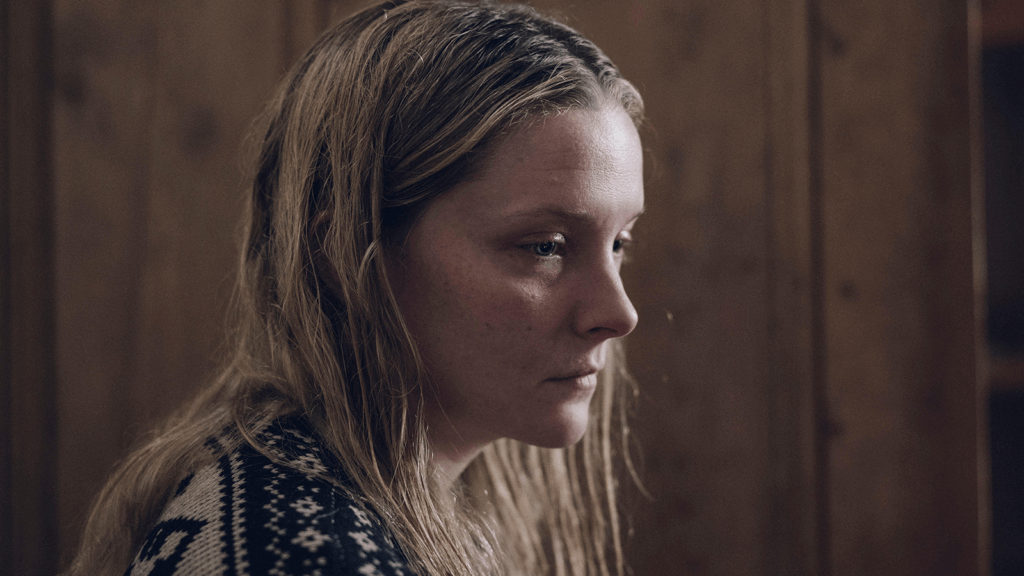

Taking more than a hint of inspiration from Don’t Look Now (1973), Kokotajlo’s approach balances the central couple’s grief with the earthbound mythology at play. Still, it’s not all unpleasant. Smith and Clark spend the entire film in a series of cozy-looking sweaters chosen by costume designer Emma Fryer, which, context aside, look inviting. Along with the rustic, brown-toned cinematography by Adam Scarth that matches the ‘70s setting, the technical presentation is impressive and never overextends the movie’s small budget. The invisible editing by Brenna Rangott occasionally cuts to bloody branches that clutch the soil beneath the family estate, implanting a sense of dread. Playing over it all, musician Matthew Herbert’s score lends the material an air of mystery and curiosity rather than horror, a compelling aural contrast with the nightmarish events onscreen. But it aligns with Richard and Juliette’s growing indoctrination.

Taking more than a hint of inspiration from Don’t Look Now (1973), Kokotajlo’s approach balances the central couple’s grief with the earthbound mythology at play. Still, it’s not all unpleasant. Smith and Clark spend the entire film in a series of cozy-looking sweaters chosen by costume designer Emma Fryer, which, context aside, look inviting. Along with the rustic, brown-toned cinematography by Adam Scarth that matches the ‘70s setting, the technical presentation is impressive and never overextends the movie’s small budget. The invisible editing by Brenna Rangott occasionally cuts to bloody branches that clutch the soil beneath the family estate, implanting a sense of dread. Playing over it all, musician Matthew Herbert’s score lends the material an air of mystery and curiosity rather than horror, a compelling aural contrast with the nightmarish events onscreen. But it aligns with Richard and Juliette’s growing indoctrination.

Elsewhere, production designer Francesca Massariol establishes an entirely believable world, where the small details have a more significant impact than the sometimes showy visuals found in this subgenre. Take the hare skeleton that Richard discovers while excavating his backyard. Hares regularly figure into British folklore, often appearing as witches in disguise, tricksters, or messengers between the living and the netherworld. Richard notices the hare’s bones begin to form sinewy flesh, and the animal entirely reanimates a day or so later. Constructed with modest yet convincing practical visuals, including an eerie puppet with vacant eyes that moves with a stiff uncanniness, the hare becomes a fixture in the household. Juliette’s sister, Harrie (Erin Richards), who has been staying with the couple, recognizes that something’s horribly wrong with the hare from the start, and also with Richard and Juliette’s fixation.

By the time Starve Acre reaches its finale, with Richard and his colleague uncovering the “womb of Nature” that leads to the spirit world, the film stops digging into the relationship and becomes preoccupied with unsettling turns. Without putting a face to the name, Kokotajlo establishes just enough about Dandelion Jack to instill fear, even though the rules around the pagan deity remain unclarified and insidiously vague. Even so, the narrative could be interpreted as one of the characters losing themselves to grief-stricken madness, similar to Clark’s performance in Saint Maud (2021), making everything that occurs in the second half open to speculation. It’s enough that the film adopts the subgenre’s tropes and finds an effective use for them while avoiding the usual references and homages frequently appearing in today’s horror cinema. Overall, Starve Acre presents a respectable entry in the increasingly popular folk horror subgenre, boasting a couple of measured, compelling performances and some chilling imagery.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review