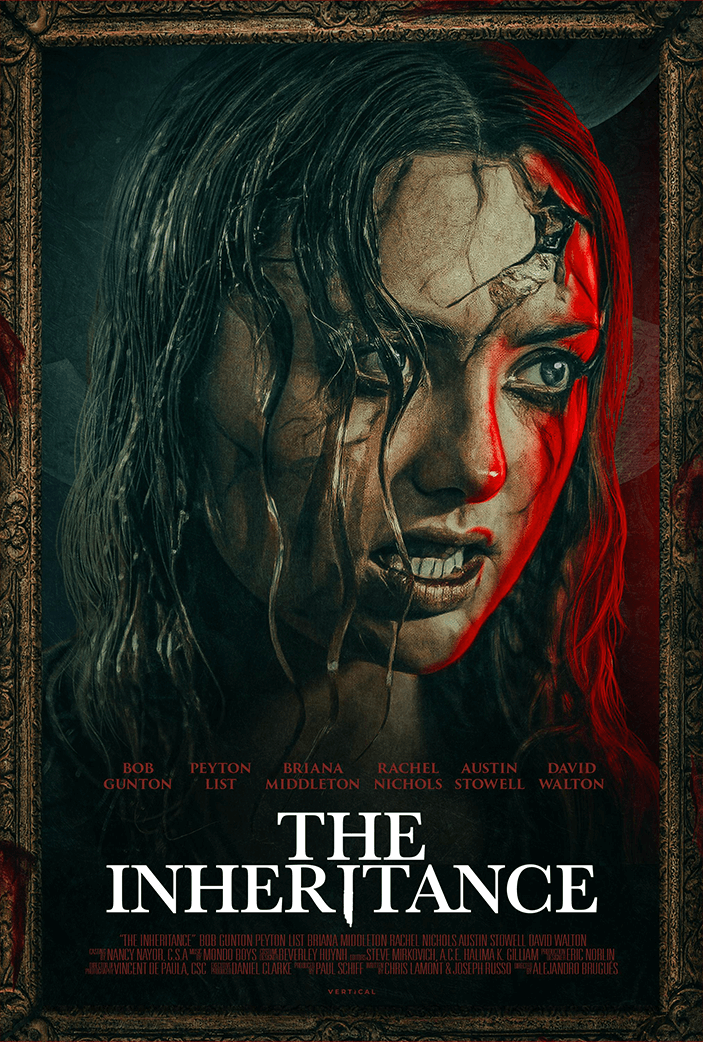

The Inheritance

By Brian Eggert |

You’ve seen this movie before, probably several times by now. The particulars have changed, but the basic setup remains the same: An assorted group of mostly detestable characters finds themselves locked in a mansion overnight. If they can survive until morning, they will receive a large financial reward. They all approach the task with varying degrees of confidence, disbelief, and trepidation. But once the first person dies, the others resolve to split up and, gradually, the body count rises, usually in the order of the actors’ popularity, with characters played by the lesser-known actors dying first. In the end, the nicest character survives, sometimes taking home the prize, sometimes rejecting the promised reward out of defiance. This same scenario goes back to House on Haunted Hill (1959) and its 1999 remake, or more recently, Escape Room (2019) and its 2021 sequel, Ready or Not (2020), and this year’s Abigail and Humane. It’s also the outline of The Inheritance, a middling iteration with a supernatural edge that neither reinvents the format nor does it very well.

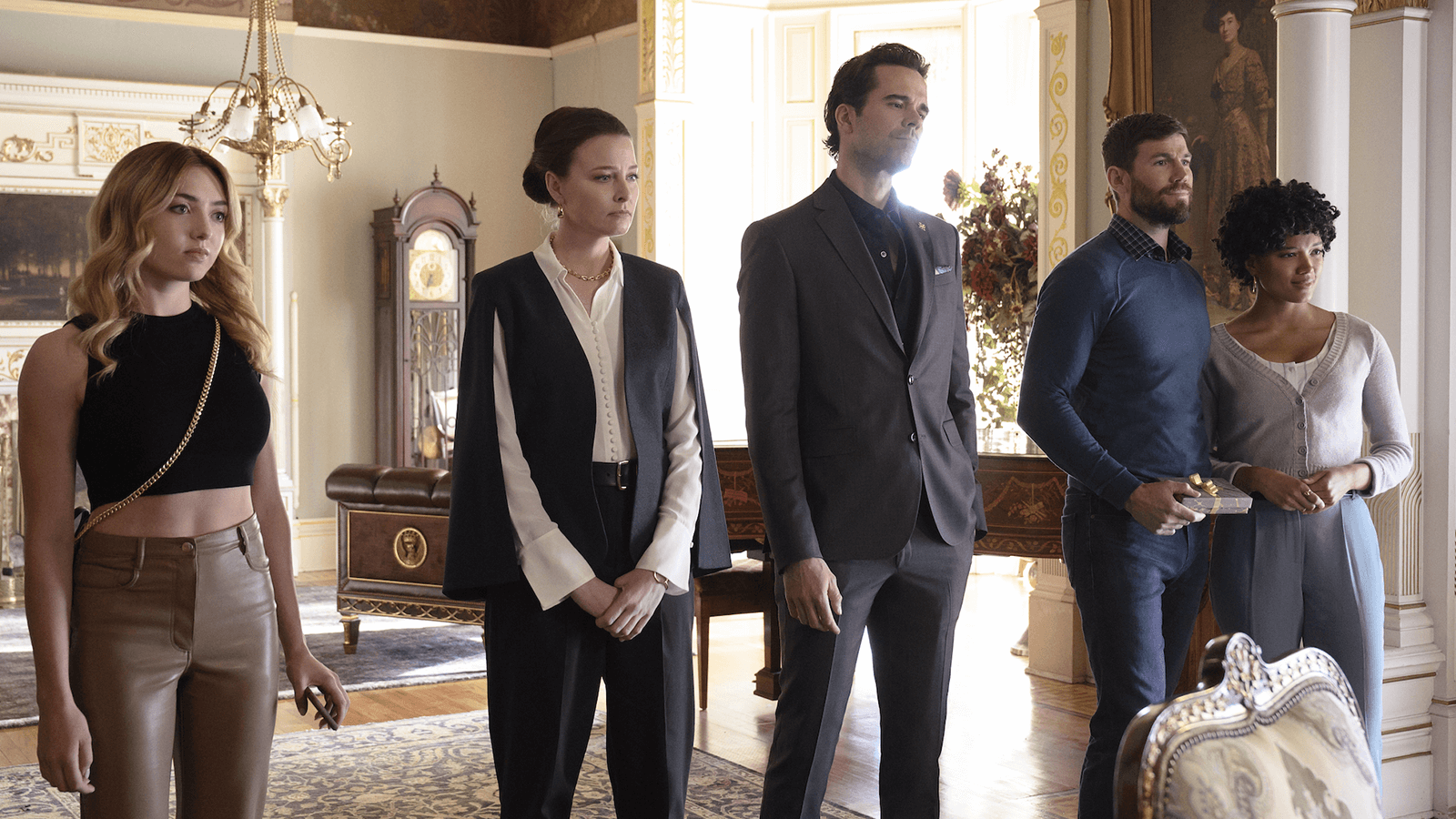

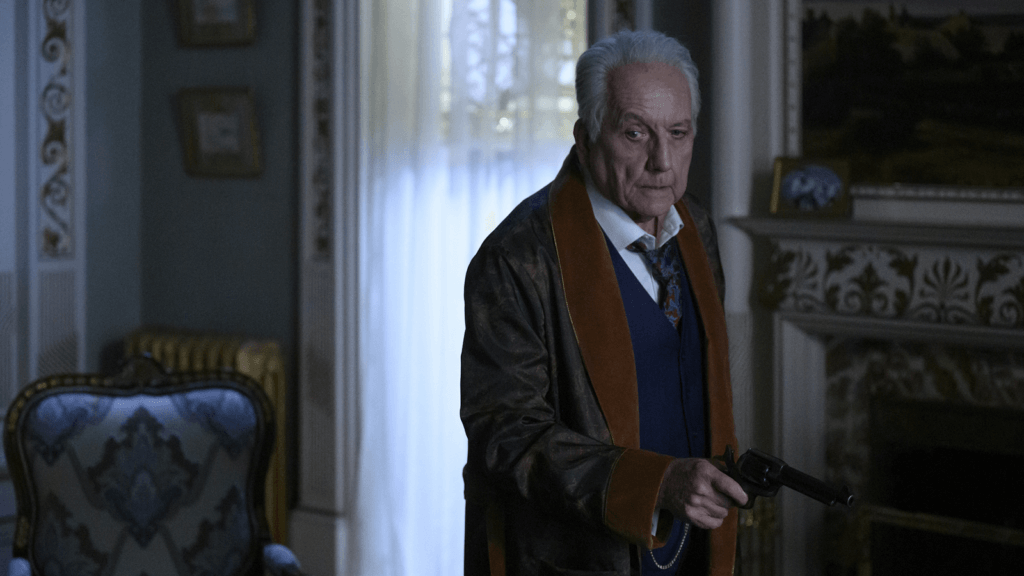

Opening with a montage of imagery alluding to demonic contracts, the movie promises something sinister ahead. A wealthy man, Charles Abernathy (Bob Gunton), has called his children to the vast and isolated Abernathy estate on his 75th birthday for a blood-relations-only meeting. Everyone arrives in black SUVs, denoting their (self)importance. The eldest siblings—fraternal twins Madeline (Rachel Nichols), the Boss Lady, and C.J. (David Walton), a conniving jerk—are the most acidic of the bunch. The youngest, Kami (Peyton List), is a vapid social media influencer, always recording for her fans and plugging her fashion line. In the middle is milquetoast Drew (Austin Stowell), who runs a charity with his wife, Hannah (Briana Middleton). After everyone grumbles that Drew has broken the rule by bringing his wife to a siblings-only family meeting, Charles announces to the group: “It’s come to my attention that there’s a price on my head.”

The contract, he claims, will be collected sometime overnight, and the children have been called upon to protect him. Charles offers Hannah the option to leave, given that she’s not a blood relative. But she vows to stay, feeling like a member of the Abernathy clan. Should Charles survive, the children will receive the billions promised to them in Charles’ will. They will get nothing should he die, and his fortune will go to a charitable foundation—a wrinkle that prompts vocal disdain from everyone but Drew and Hannah. Moreover, they will all be locked inside until the next morning, with the doors and windows reinforced, making the mansion inescapable. The question remains: Who wants to kill Charles, and why? The paterfamilias’ vague explanation offers few clues, and the children seem content not to ask many questions, apparently afraid to challenge their father. Though, judging by Charles’ affinity for Faust, the viewer might guess what’s in store.

The problem is that the movie doesn’t care about its characters as people. Screenwriters Chris LaMont and Joe Russo spend little time developing fleshed-out relationships or personalities, leaving each inevitable victim a one-note construction. Consider how the children react to their situation. Despite the chilling setup, they do not strategize or even speculate. They separate and, for some reason, resolve to walk around the mansion in the dark. Cue the customary signs that something evil is afoot, such as a pool table that resets itself, a wind-up toy that plays on its own, and shadowy figures lurking in the dark. At the same time, Madeline and C.J. plot a company takeover, feeding on each other’s jealousy and paranoia, convinced that their father has lost his mind and that Drew and Hannah are plotting against them.

The problem is that the movie doesn’t care about its characters as people. Screenwriters Chris LaMont and Joe Russo spend little time developing fleshed-out relationships or personalities, leaving each inevitable victim a one-note construction. Consider how the children react to their situation. Despite the chilling setup, they do not strategize or even speculate. They separate and, for some reason, resolve to walk around the mansion in the dark. Cue the customary signs that something evil is afoot, such as a pool table that resets itself, a wind-up toy that plays on its own, and shadowy figures lurking in the dark. At the same time, Madeline and C.J. plot a company takeover, feeding on each other’s jealousy and paranoia, convinced that their father has lost his mind and that Drew and Hannah are plotting against them.

Running a mere 84 minutes, The Inheritance was directed by Alejandro Brugués, the skilled filmmaker behind Juan of the Dead (2011) and segments in horror anthologies such as Nightmare Cinema (2018) and Satanic Hispanics (2022). Evidence of his smart approach to scary scenes can be found in a sequence with Kami, who decides to explore the indoor pool in the dark. The scene plays out like the opening of Jaws (1975), except, instead of watching the victim from the water’s surface and wondering what’s below, he reverses it. The camera remains underwater, and Brugués shows Kami’s feet dangling in the pool. Her feet suddenly become tense. We gather that something has taken hold of her, and it drags her over the pool before lifting her in the air. Beneath the surface, we see only her feet disappear and blood drop into the water, with the grisly details cleverly left to our imagination.

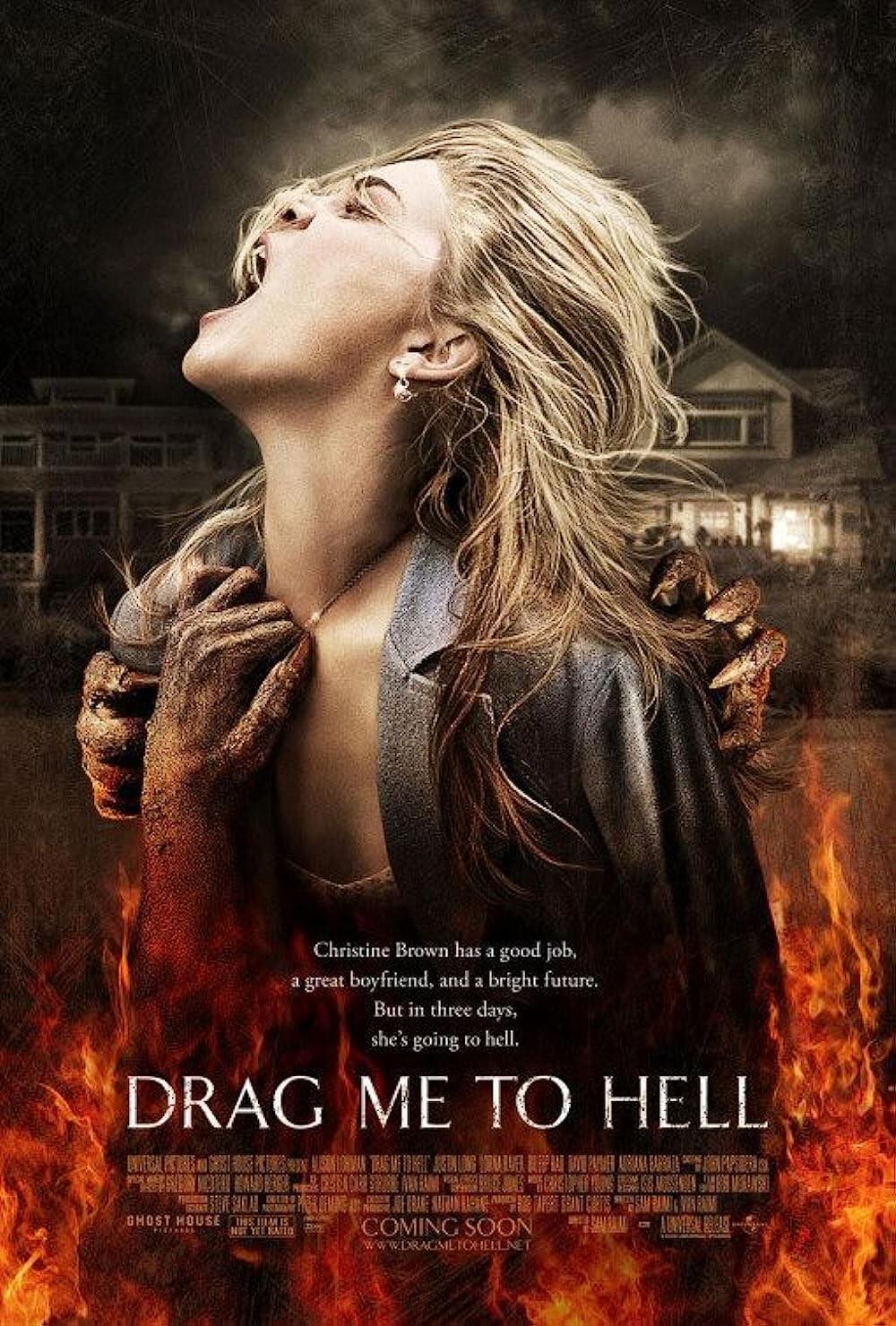

After that inspired sequence, the movie returns to its banal mode. The siblings barely shed a tear over poor Kami. They ask few questions about what happened or how to proceed, further suggesting their lack of humanity or the inadequate screenplay. Ghosts appear. Another creepy sequence involves Kami’s specter climbing out of a painting, but its imagery is perhaps too closely inspired by The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Drag Me to Hell (2009). There’s also an ominous storage room sequence with historical artifacts that turn to look at Drew and Hannah as they try to escape the mansion, as if to say, “Whaddya think you’re doing?” A recurring motif involves the family members announcing themselves to each other with the old “shave and a haircut, two bits” knock, which is a not-so-secret code they use. To be sure, the filmmakers have few original ideas here. Worse, they don’t explore these well-trodden ideas with much inspiration.

Watching The Inheritance late at night, with lowered expectations, one might find the material serviceable and mercifully short. But its ideas will be familiar, including the rich people are the worst theme. Its character and plot tropes have been done before, and better. The movie introduces few novel flourishes or innovations on this familiar setup, and it does nothing to stand out from the crowd, not even from similar 2024 efforts. The few neat horror sequences mentioned above, along with others left unmentioned, prove adequately diverting. But the movie does little more than supply proof that Brugués’ talent outweighs the material he chooses to direct. As the filmmaking adage goes, not even a gifted director can make a good movie out of a bad script.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review