Short Takes

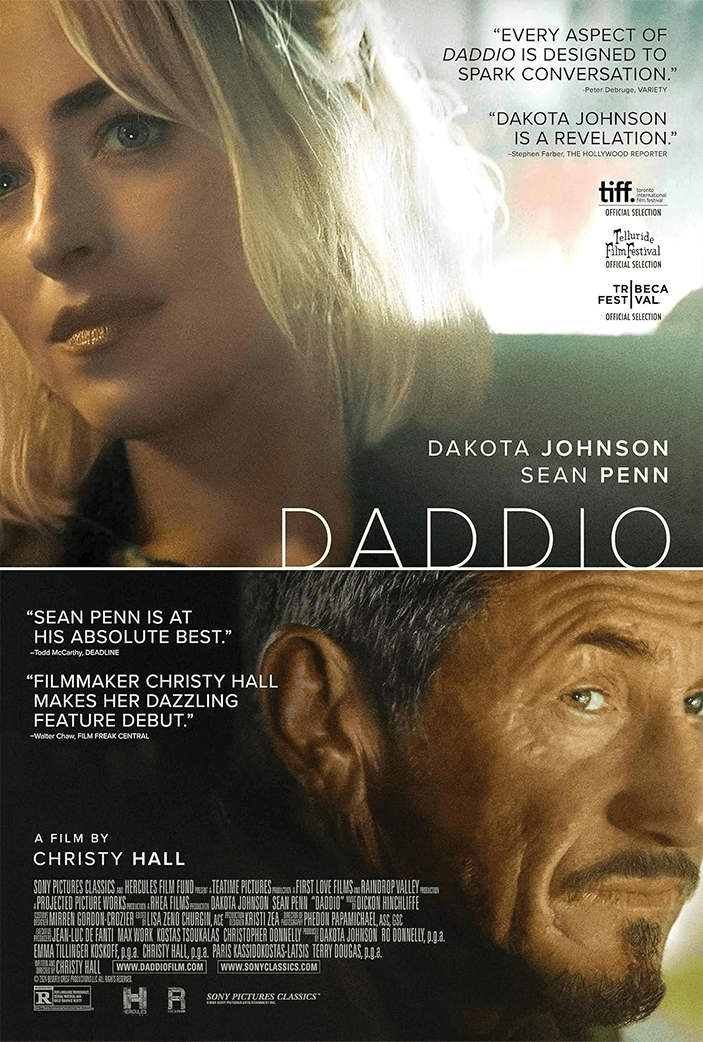

Daddio

By Brian Eggert |

Originally developed as a stage drama, Christy Hall’s directing debut, Daddio, plays like a movie version of HBO’s 1990s phenomenon, Taxicab Confessions. It’s a naturally dramatic arena. The spatial limitations of a cab ride, coupled with an extended period alone with a stranger, make for a distinct stage on which one can let their guard down and reveal hidden aspects of their inner lives to someone they’ll likely never see again. Pulling off a feature-length narrative in this setting, with just two actors in a confined space for 101 minutes, is an accomplishment. However, the content of Hall’s spec script proves too familiar and somewhat generic; though, her assured direction and the measured pacing denote an evident talent at work. The film is a showcase for its two leads, but above all else, it’s impressive for how cinematographer Phedon Papamichael and editor Lisa Zeno Churgin make the limited scale feel visually alive and unrepetitive, and watching the ensuing conversation feels more engaging than it might be without its technique.

In a situation that might seem impossible for those of us who find taxis or rideshare conversations awkward, an unnamed woman, played by Dakota Johnson, gets a cab from JFK International Airport to her Manhattan apartment. After a few establishing scenes in the airport, the action unfolds entirely in the car, driven by Clark (Sean Penn). He starts by making small talk, muttering about apps and tipping culture. Then he compliments her, observing that she’s not like other people—she isn’t glued to her phone and even looks him in the eye. “You can handle yourself,” he admires. Before long, some unexpected delays on the road mean the setting is not only limited but static. Immobile, Clark asks question after question, sometimes pervy, which she accommodates. Their conversation leads to a mutual sharing of their backstories and worldviews, particularly on power and the differences between men and women, and what each gender wants, love or sex. All the while, she secretly exchanges texts with her married lover, unsure of how to define her affair, as a sexual fling or genuine love—though, the answer is pretty clear to Clark and the audience.

If one didn’t know any better, they might mistake Daddio for a COVID-era production, developed and shot with limited locations and actors in adherence to pandemic restrictions. But it was shot in 2022. To be sure, there were small, intimate two-handers before Hall’s film, and there will be plenty after it. Unlike, say, My Dinner with Andre (1981) or Venus in Fur (2013), the conversions here feel at most two layers deep into the characters’ psyches, despite Hall’s spec script appearing on 2017’s “Black List” of the best unproduced screenplays. Johnson, who also produced, and Penn elevate their roles, playing the resident patient and shrink, respectively. Still, using banal generalities and recognizable character types that don’t deviate from their tropes, Hall hardly digs deep into tired assumptions about gender roles and behaviors through her characters, bringing no new ideas about humanity or relationships to the proceedings. Lacking character developments that resonate with much profundity, it will probably be low-key relatable for many, but it neither feels like vital cinema nor leaves much of a lasting impression.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review