The Babadook

By Brian Eggert |

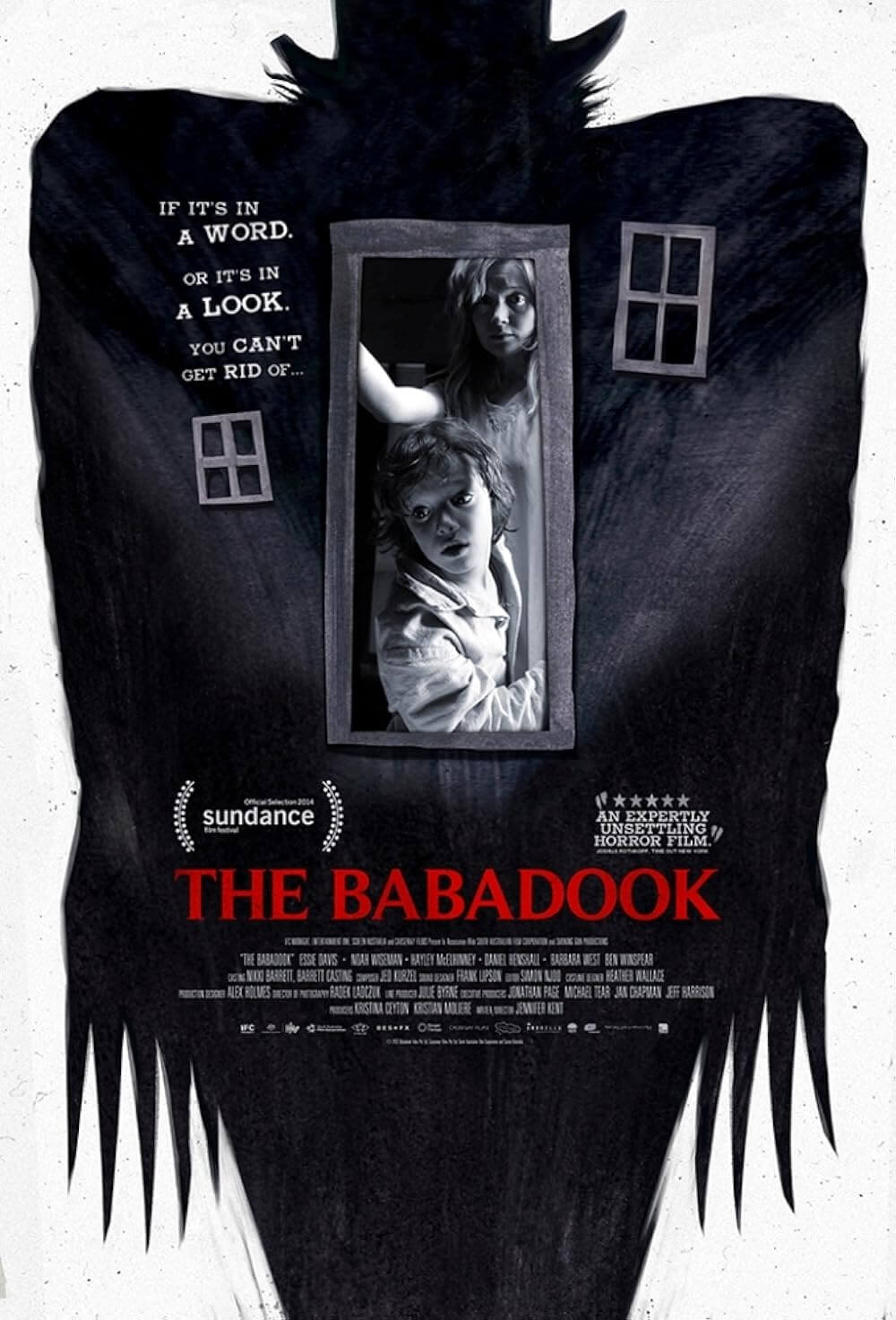

Samuel’s mother Amelia dreads his upcoming birthday because it’s the day her late husband died in an accident while driving her to the hospital to give birth. Nearly seven years have passed, and raising Samuel minus a father has taken its toll. Not only is she still filled with a widow’s grief and loneliness, but her son is a handful. And then some. She can barely support them with her job as a nurse at a senior care facility, and she’s at a loss as to how to handle Samuel’s outbursts and dogged belief in imaginary monsters. To protect his mother from said monsters, he builds dangerous weapons, and even worse, he acts out at school and at home. One night, Amelia reads him a story from a book on his shelf that she does not recognize and offers no author credit. It’s called “Mr. Babadook.” Bound in red and black, the pop-up book rhymes about its titular monster, warning that once he knocks at your door to get in your house, he’s there to stay. And no matter how Amelia tries to rid herself of the book or the idea of the book, or how much she tries to convince Samuel that it isn’t real, she finds its nursery rhyme to be true: “If it’s in a word, or it’s in a look, you can’t get rid of the Babadook.”

Rich with dramatic metaphor and frightening imagery, Australian writer-director Jennifer Kent has executed the most effective, most rewarding horror film in recent memory with The Babadook. An expansion of her short film “Monster,” Kent explores a demanding scenario that is all the scarier because the filmmaker has constructed a dramatically tense situation to draw our emotional involvement. What’s more, the experience is grueling because the imposing imagery employed is truly the stuff of nightmares. Distributed by IFC Midnight, positive word-of-mouth may allow this unrated, independent release to garner deserved attention; and indeed, it should be sought out by those who appreciate complex and challenging material. To be sure, the film is not for the faint of heart, nor is it for the intellectually dim, otherwise accustomed to standard spooky fare like Insidious or The Conjuring. There’s an emotional cause behind every horrible turn, recalling the genre’s best entries such as The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby.

Essie Davis plays Amelia behind tired eyes and ragged hair, the strain of her son’s outbursts wearing on her. He’s a troubled boy, played by Noah Wiseman with amazing intensity—the kind of intensity that makes you wonder how the filmmakers incited the volatile performance, and also wonder what’s wrong that a child actor can make his character’s disturbed state so believable. For much of the film, the audience is convinced that Samuel might end up like the anguished, psychotic youngsters in Joshua or We Need to Talk About Kevin. He acts out in alarming ways, bringing his homemade weapons to school and pushing his cousin out of a treehouse. While claiming that he’s just trying to protect himself and his mother from Mr. Babadook, he’s also carrying around the weight of repressed blame and guilt for his father’s death. He casually mentions to strangers that his father died on his birthday, and so his mother refuses to celebrate the occasion on that particular day. What child could process such trauma without some sort of psychological consequence that, over time, manifests in other ways?

And so, when Samuel screams bloody murder that Mr. Babadook is in his closet or under his bed, one almost has to assume that his behavior is the result of a troubled psyche. Everything that happens early on has a logical, and, more importantly, psychological explanation. But once Amelia resolves to destroy the book by tearing out its pages, it somehow finds itself repaired and back on her doorstep, now with additional pages that seem directed toward her in scary ways. Before long, she’s seeing what her son sees—a tall, cloaked figure shrouded in shadows, his long, straight fingers spread out like thorns, his pale face a work of pure German Expressionism—and then she wants nothing more than to isolate themselves. Illustrator Alex Juhasz created the eerie images in the gothic storybook, which seem inspired by The Cabinet of Dr. Calgari, Francis Bacon, and various tales of the boogeyman. The book itself does such a superb job of filling our imagination with terror, and what little Kent shows us onscreen is enhanced by our fearful anticipation of its appearance.

And so, when Samuel screams bloody murder that Mr. Babadook is in his closet or under his bed, one almost has to assume that his behavior is the result of a troubled psyche. Everything that happens early on has a logical, and, more importantly, psychological explanation. But once Amelia resolves to destroy the book by tearing out its pages, it somehow finds itself repaired and back on her doorstep, now with additional pages that seem directed toward her in scary ways. Before long, she’s seeing what her son sees—a tall, cloaked figure shrouded in shadows, his long, straight fingers spread out like thorns, his pale face a work of pure German Expressionism—and then she wants nothing more than to isolate themselves. Illustrator Alex Juhasz created the eerie images in the gothic storybook, which seem inspired by The Cabinet of Dr. Calgari, Francis Bacon, and various tales of the boogeyman. The book itself does such a superb job of filling our imagination with terror, and what little Kent shows us onscreen is enhanced by our fearful anticipation of its appearance.

In that sense, Kent’s treatment is masterful in how she uses our imaginations to build up the Babadook, and then she delivers him in expert cinematic reality. Moreover, she creates a highly stylized mise-en-scène constructed as a contained environment from which Amelia and Samuel are afraid to leave so as not to expose anyone to Samuel’s outbursts, but inside they’re also exposed to a frightening blend of psychological and real horror. Production designer Alex Holmes and set designer Ross Perkin create a house of pale and dark blues on the walls and trim, bordering on the level of style you might find in a Tim Burton interior—all shot in crisp detail by cinematographer Radoslaw Ladczuk. Every wall and piece of furniture has a deliberate placement, almost as though The Babadook takes place on stage—and, despite a few exterior scenes, the film could easily be adapted to the theater. Best of all, Kent’s treatment avoids strict adherence to genre rules; she refuses to make this a typical supernatural yarn, and instead of using her supporting cast (sister Claire, played by Hayley McElhinney, and an old neighbor played by Barbara West) to increase the body count, she uses them to deepen her central characters.

The Babadook is about as sophisticated as such spookhouse territory gets, and Kent’s confident filmmaking remains impressive throughout. Perhaps the only elements that compare to Kent’s approach are Davis and Wiseman’s performances, especially the latter, since the inexperienced young actor fully commits to his disturbed youngster role with a shockingly mercurial presence, sending us further into the story. But it’s how Kent balances the film’s unnerving storybook quality, genuine scares, and its deep-rooted psychological impetus that leave us in full awe of how well The Babadook has been assembled, and how it walks the fine line between reality and nightmares with skilled footing. Recently, William Friedkin (The Exorcist) remarked, “I’ve never seen a more terrifying film… It will scare the hell out of you as it did me.” He’s since tried to get wider distribution, but its unrated status will likely prevent that. And there’s a simple, justified reason Friedkin has spoken out and become a huge activist for the film: it’s great, and greatly terrifying, and deserves to be discovered.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review