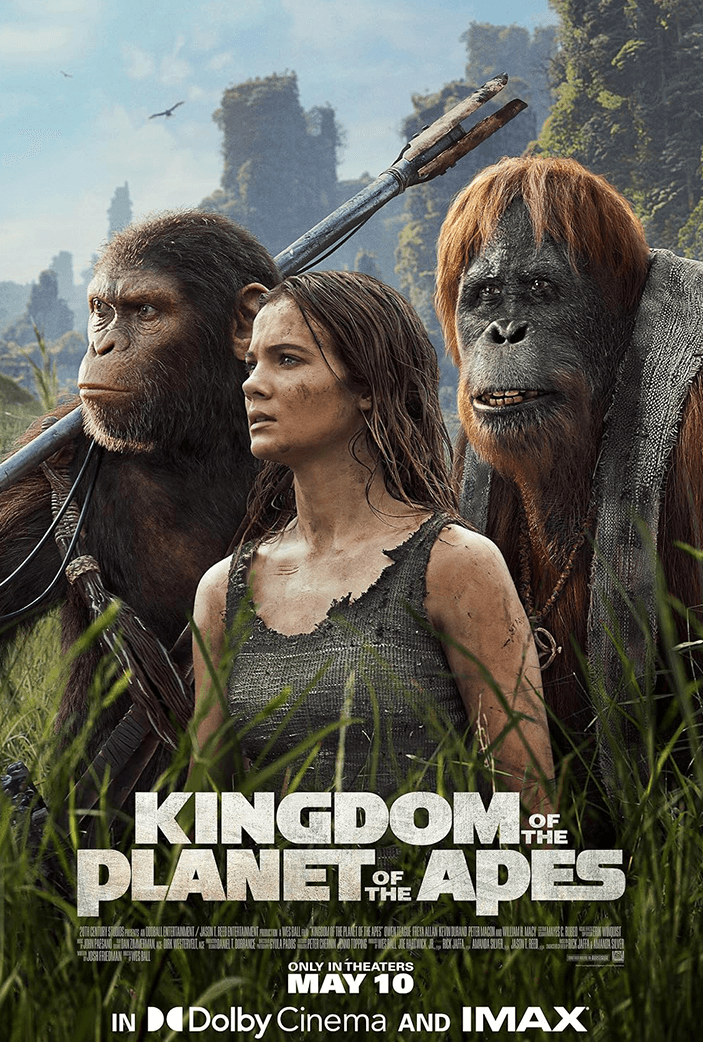

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

By Brian Eggert |

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is the first entry in what was a 20th Century Fox property before Disney acquired the studio in 2019. The fourth installment of the reboot franchise that started in 2011 with Rise of the Planet of the Apes is another soft reset, involving new characters, new talent behind the camera, yet the same visual technique that deploys stunning motion-capture CGI to render lifelike apes who talk, emote, and convince us of their corporeality. After helming the last two entries, Matt Reeves, now overseeing The Batman series at Warner Bros., hands the baton to director Wes Ball, best known for helming the Maze Runner movies, based on the popular YA books. Ball is a serviceable replacement, delivering a competent and visually impressive sequel, albeit without some of the awe-inspiring visual panache of the films under Reeves. The cast, too, feels like the B-squad, with a few recognizable names but no real star power. Regardless, the apes remain the attraction here, and Kingdom feels like its own beast. Screenwriter Josh Friedman (next year’s The Fantastic Four) shows a palpable interest in theme and character over empty spectacle and action set pieces, resulting in a smarter-than-average popcorn movie.

The Planet of the Apes franchise has been around for nearly 60 years. In that time, there have been ten movies, including Kingdom, and three separate cinematic continuities. The original series, starting with the 1968 film—a masterpiece based on Pierre Boulle’s groundbreaking 1963 novel—remains a watershed moment in science fiction. Four sequels followed with mixed results, alternately veering into camp and schlock but each worthy of attention. Tim Burton attempted a reboot in 2001, offering a production notable for its incredible costumes and simian makeup, but it was saddled with a dull leading man and a laughably confounding ending. However, the so-called Caesar Trilogy that began in 2011 had the potential to elevate the intellectual property. It is this critic’s opinion, a minority one though it may be, that Reeves failed to stick the landing due to the overreliance on biblical imagery and heavy-handed cinematic reference points throughout War for the Planet of Apes (2017). And while Kingdom maintains its share of allusions to religion and politics, the film uses them in a subtler and more clever way.

The story begins with the end of Caesar, the protagonist of the last three installments, being laid to rest on a funeral pyre. It also marks the end of Andy Serkis’ presence after revolutionizing mo-cap performances with characters such as Caesar, Gollum, and King Kong. “Many Generations Later,” we meet Noa (Owen Teague) and other chimpanzee members of the Eagle Clan, who still talk with the speech patterns of English neophytes and intermittently use ASL. They train birds of prey, perhaps as the symbol of their unity with Nature. But Noa and those in his village are not the only ape clan. Another group, wielding electric prods and determined to capture other apes, raids Noa’s village early in the film, leaving his “Master of Birds” father dead and taking his family and friends captive. In the aftermath, Noa sets out to find them. Along the way, he makes a friend in the wise orangutan Raka (Peter Macon, excellent), and they’re both followed by a human, Nova (Freya Allan), from a species his clan calls “echo.” Raka and the apes in Noa’s tribe believe humans have no more intelligence than warthogs and cannot speak. But Noa soon learns that his preconceptions about humans are wrong; as it turns out, so are his assumptions about other apes.

Kingdom loses much of its humor and joy after Raka, with his comically backward beliefs about the human-ape dynamic, disappears early on—he’s such a well-drawn and realized character that the movie is never better than his scenes. Eventually, Noa finds himself in the presence of Proximus Caesar (Kevin Durand), the crowned and self-declared king of “stolen clans” such as Noa’s. But Proximus is no Caesar, despite counting hundreds of apes among his followers—including one lowly human, Trevathan (William H. Macy), who’s relegated to teaching Proximus about ancient Rome. The hero of the last three movies has since become a Christlike figure, as suggested by the end of War. For instance, the window in Caesar’s attic bedroom from Rise has become a crucifix-like symbol for the fallen leader, worn around Raka’s neck and stenciled on the rusty ships that represent Proximus’ kingdom walls. Caesar’s lesson—“Apes… Together… Strong.”—is repeated by various apes, recalling devout Christians who recite biblical verses like a mantra. “For Caesar!” his followers declare with zealous commitment. And also, “Caesar will forgive” small offenses. After a few of Raka’s cursory lessons, even Noa becomes a converted member of Raka’s Order of Caesar, quickly drinking the Kool-Aid on Caesar’s importance.

Kingdom loses much of its humor and joy after Raka, with his comically backward beliefs about the human-ape dynamic, disappears early on—he’s such a well-drawn and realized character that the movie is never better than his scenes. Eventually, Noa finds himself in the presence of Proximus Caesar (Kevin Durand), the crowned and self-declared king of “stolen clans” such as Noa’s. But Proximus is no Caesar, despite counting hundreds of apes among his followers—including one lowly human, Trevathan (William H. Macy), who’s relegated to teaching Proximus about ancient Rome. The hero of the last three movies has since become a Christlike figure, as suggested by the end of War. For instance, the window in Caesar’s attic bedroom from Rise has become a crucifix-like symbol for the fallen leader, worn around Raka’s neck and stenciled on the rusty ships that represent Proximus’ kingdom walls. Caesar’s lesson—“Apes… Together… Strong.”—is repeated by various apes, recalling devout Christians who recite biblical verses like a mantra. “For Caesar!” his followers declare with zealous commitment. And also, “Caesar will forgive” small offenses. After a few of Raka’s cursory lessons, even Noa becomes a converted member of Raka’s Order of Caesar, quickly drinking the Kool-Aid on Caesar’s importance.

Proximus, much like certain political leaders, has weaponized a popular religion to present his leadership as more than a mere elected official or self-appointed royalty—he advances the notion that his reign is mythic and, therefore, less about his quality of leadership than the belief system he invokes. To be sure, the film has much on its mind regarding how religions develop and what people extract from them, specifically the people in charge. Friedman’s intelligent writing does this without overemphasizing the modern-day parallels, though the script lends itself to interpretation. Of course, Proximus also has a Master Plan. He knows about human intelligence, science, and theories from Trevathan, and he wants “instant evolution” from the technology inside an underground vault—a human bunker filled with who-knows-what to make Proximus an almighty ruler.

Kingdom is Ball’s most accomplished work to date, both dramatically and visually; the director makes excellent use of his $165 million budget to deliver a convincing post-human world. Though, at times, it feels like the environment’s designers played many hours of The Last of Us: Part 2 before conceiving this overgrown vision of the Pacific Northwest, complete with wild zebra herds and skyscrapers wrapped in vegetation. Gyula Pados, Ball’s cinematographer on the Maze Runner series, once again presents a dystopian world in bright, clear lighting, with most of the movie taking place during sunny days. Generally, the presentation is cohesive but not necessarily evocative or memorably stylized. And while Ball resists the onslaught of movie references that Reeves embedded into War, he includes a few visual nods to the 1968 film and familiar notes on John Paesano’s score that recall the original’s music by Jerry Goldsmith. Ball also directs several marvelous performances. Durand shines as Proximus, the dim, power-hunger leader, and Teague captures Noa’s sensitivity and inner strength.

The most compelling aspect of Kingdom involves Noa’s maturation. The film opens with Noa, joined by compatriots Anaya (Travis Jeffery) and Soona (Lydia Peckham), performing a right of passage that entails climbing to a high nest and acquiring an eagle egg, which Noa must protect until it hatches. By the end, though he loses his initial egg, Noa has learned much about how the world works, from how leaders manipulate their followers to how people will do anything, no matter how duplicitous, to preserve their clan or species. In that respect, the movie isn’t sure where the audience should place its sympathies. Should we root for Noa, the kindly, smarter-than-the-average-ape member of the peaceful Eagle Clan? Should we root for the humans, represented by Nova, an intelligent human, at least by Raka’s standards for the species? In the end, who does the human audience want to see survive and dominate the planet, apes or humans? Should anyone dominate? Or is it just the nature of intelligent life to want to conquer, establish power, organize, and rule?

The most compelling aspect of Kingdom involves Noa’s maturation. The film opens with Noa, joined by compatriots Anaya (Travis Jeffery) and Soona (Lydia Peckham), performing a right of passage that entails climbing to a high nest and acquiring an eagle egg, which Noa must protect until it hatches. By the end, though he loses his initial egg, Noa has learned much about how the world works, from how leaders manipulate their followers to how people will do anything, no matter how duplicitous, to preserve their clan or species. In that respect, the movie isn’t sure where the audience should place its sympathies. Should we root for Noa, the kindly, smarter-than-the-average-ape member of the peaceful Eagle Clan? Should we root for the humans, represented by Nova, an intelligent human, at least by Raka’s standards for the species? In the end, who does the human audience want to see survive and dominate the planet, apes or humans? Should anyone dominate? Or is it just the nature of intelligent life to want to conquer, establish power, organize, and rule?

These questions linger after Kingdom is over in a way that challenges the viewer. After the last three entries, which were firmly on the side of Caesar and portrayed humans as destructive and dangerous, Kingdom’s suggestion that humanity may rise again should feel ominous; instead, it feels hopeful. The lesson, I suppose, is that we all exist under the same stars—a point made in a subplot involving an observatory telescope—so why not try to get along? But the movie also acknowledges that, while individuals from different backgrounds, even species, can connect, groups of people (apes included) tend to fear Otherness and demand conformity. Kingdom packages these ideas in a fast-paced, 145-minute blockbuster that balances relevant themes with an impressive visual treatment. It doesn’t sing with the full-throated enthusiasm of Rise and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), but it’s a worthy sequel and promising start to what one hopes will become a new trilogy.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review