Evil Does Not Exist

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This film was screened at the 43rd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. The film arrives in theaters via Janus Films and Sideshow on May 17, 2024, at The Main Cinema in Minneapolis.

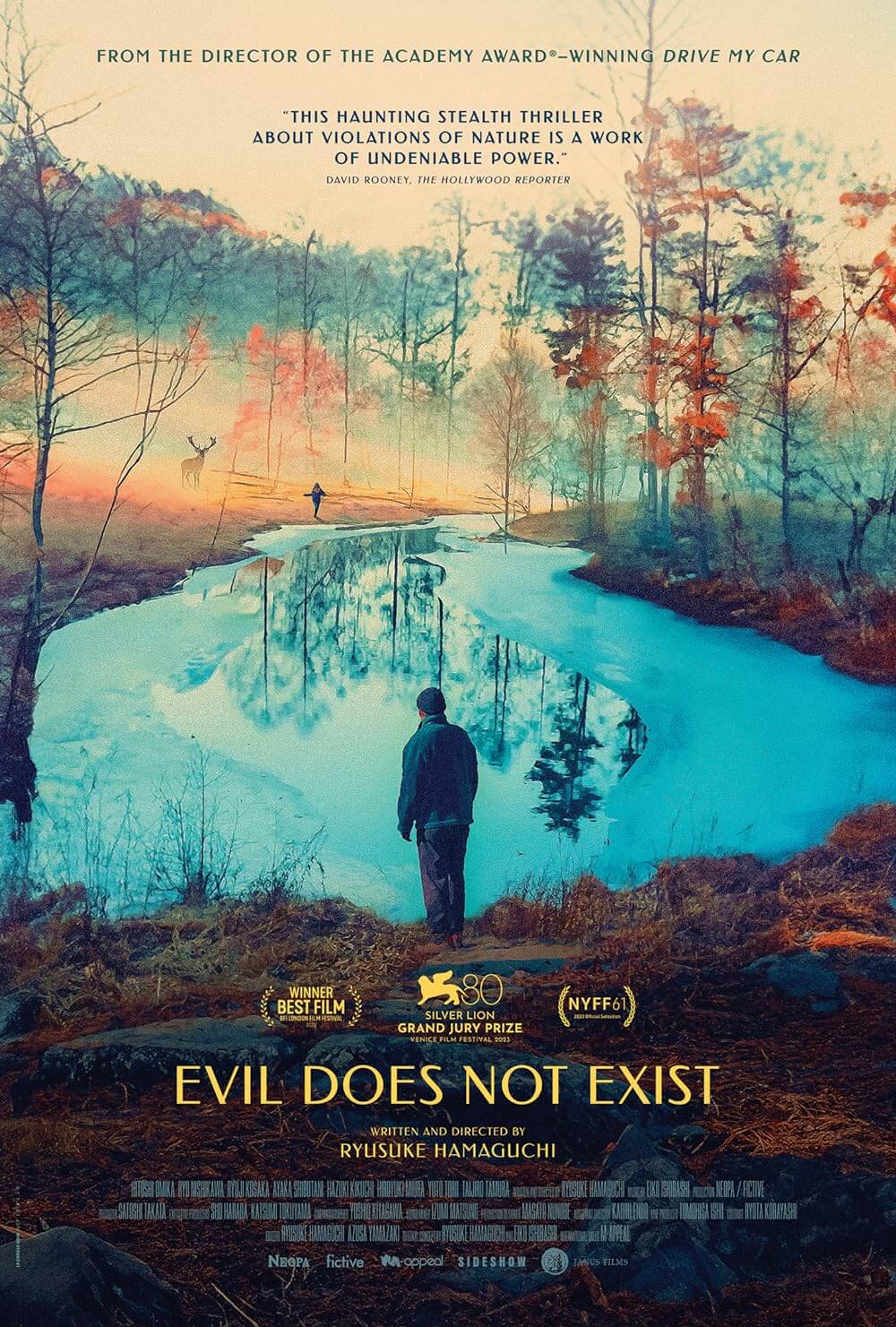

Evil Does Not Exist is a meditation on humanity’s relationship with and encroachment on the natural world. The film takes place a few hours north of Tokyo, in Mizubik, a sleepy mountain town surrounded by freshwater streams, animal life, and mostly untouched wilderness. The first shots look up at forest trees in winter, framing the overcast sky with skeletal branches. Composer Eiko Ishibashi’s electronic score implants an eerie brooding underneath these harmonious images, aurally suggesting the tension between people and Nature at the center of writer-director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s haunting, quietly immersive film. After his Oscar-winning feature Drive My Car (2021), Hamaguchi’s latest offers a new facet to his concerns as a filmmaker, examining how people interact with and disrupt their natural surroundings. Most of Hamaguchi’s output involves alienated people who inhabit metropolitan spaces and attempt to make meaningful connections with one another. A thoughtful and even challenging low-key eco-thriller, Evil Does Not Exist considers the relationship between people and their environment as fraught with disruptive forces, both in how humanity corrupts the environment and also in how Nature fights back.

Hamaguchi portrays this relationship in fragile terms, as though the natural world were a thin sheet of ice and, with each step a person takes, it cracks. Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), a handyman who maintains close ties with his surroundings, knows this better than most. He lives off the land with his young daughter, Hana (Ryô Nishikawa), in an isolated home in the woods. Several sequences entail Hana and her father walking through the forest, and their footsteps compacting the snow seem to ring out in the forest’s silence. Hana identifies trees as her father taught her; he also shows her how to look for signs of deer in the local fauna. But even the most conscious preservers of the natural world infringe on their surroundings. Hamaguchi and co-editor Azusa Yamazaki deploy a startling cut that finds Takumi chainsawing logs, the sound breaking the quiet with a deafening buzz. Takumi then chops the wood for his fireplace, and each impact sounds like a violation. Takumi and other Mizubik community members represent the lowest possible impact of humans on Nature. And yet, every once in a while, a gunshot echoes in the distance. Occasionally, that shot hits a deer in the gut. Sometimes, the animal gets away and needlessly dies, leaving the hunter without sustenance and, more significantly, the animal’s life wasted. Sometimes, a human encounters a gutshot deer, and the animal fights for its life.

Hamaguchi conceived his film in a conceptual art collaboration with Ishibashi, who asked the director to provide video footage to accompany her music. The outcome, titled Gift, included Hamaguchi’s thirty-five-minute silent film footage with Ishibashi’s music, performed live for an audience. The director then expanded on his footage for Gift, turning the project into a feature-length narrative. Ishibashi expanded her score as well, adding an occasional synth sound and curiously artificial dimension to Hamaguchi’s film, with its entrancing, almost ‘80s-style thriller tones set against natural images, accenting the dichotomy between what humans create and how that clashes with our environment. If Nature functions in a series of “movements,” as Hamaguchi suggests in the press notes, humans interrupt those movements with their presence through building or simply interrupting a stream to collect water. With the two works of art orbiting around one another, one focused on music and image, the other on image and narrative but accented by music, there’s a fascinating artistic exchange occurring for those fortunate enough to see Gift. For the rest of us, Evil Does Not Exist presents a different kind of Hamaguchi film, where the power of natural images is all-consuming.

Hamaguchi shows the people of Mizubik yearning for harmony with Nature. For instance, a restaurateur (Hazuki Kikuchi) moved there from the city, aware of how even mildly contaminated water affects the flavor of her udon noodles, which taste better when boiled in Mizubik’s fresh spring water—gathered by Takumi in plastic containers from a nearby stream. But that harmony is threatened when PR representatives Takahashi (Ryûji Kosaka) and Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani) arrive in town to address the community on behalf of Playmode, a glamping (“glamorous camping”) company. In the film’s most engaging sequence, reminiscent of the town hall debate in last year’s R.M.N., the reps present Playmode’s technical plans and listen to the community’s concerns. They remain at a loss when Takumi and others point out the central flaw in the proposed glamping site’s septic tank location, which will contaminate local water. “A little pollution won’t affect the water,” they insist. But would you drink water knowing it was even mildly tainted with sewage and chemicals? As the village elder (Taijirô Tamura) wisely observes, “What you do upstream will end up affecting those living downstream.”

Hamaguchi shows the people of Mizubik yearning for harmony with Nature. For instance, a restaurateur (Hazuki Kikuchi) moved there from the city, aware of how even mildly contaminated water affects the flavor of her udon noodles, which taste better when boiled in Mizubik’s fresh spring water—gathered by Takumi in plastic containers from a nearby stream. But that harmony is threatened when PR representatives Takahashi (Ryûji Kosaka) and Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani) arrive in town to address the community on behalf of Playmode, a glamping (“glamorous camping”) company. In the film’s most engaging sequence, reminiscent of the town hall debate in last year’s R.M.N., the reps present Playmode’s technical plans and listen to the community’s concerns. They remain at a loss when Takumi and others point out the central flaw in the proposed glamping site’s septic tank location, which will contaminate local water. “A little pollution won’t affect the water,” they insist. But would you drink water knowing it was even mildly tainted with sewage and chemicals? As the village elder (Taijirô Tamura) wisely observes, “What you do upstream will end up affecting those living downstream.”

The two corporate functionaries can hardly argue with that, especially Mayuzumi, who questions the entire project. But back in Tokyo, when they present the town’s logical arguments against Playmode’s lousy planning, their boss admits the project is full of holes yet wants to proceed anyway. He suggests enlisting Takumi as the glamping site’s caretaker to smooth over any concerns. However, the more time Takahashi and Mayuzumi spend in Mizubik trying to convince Takumi, the more they realize their presence is a violation. They begin to appreciate the austerity and purity of Nature, although Takahashi in particular remains out of sync. Amusing scenes find him struggling to chop wood properly or vaguely insulting the local chef by remarking that her noodles warmed him up. “That’s got nothing to do with taste,” she replies flatly, insulted that he has no substantive take of her cuisine. Takahashi doesn’t quite get it. Similarly, they present their plan to Takumi, who rejects their offers and points out that a deer trail passes through the proposed glamping site. Where will the deer go? “Somewhere else,” Takahashi responds.

Starting with Passion (2008), his first feature-length project completed as part of the graduate program at the Tokyo University of the Arts, and followed by Happy Hour (2015), Asako I & II (2018), and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021), Hamaguchi has told stories about interpersonal relationships in urban settings. Surrounded by vast cityscapes and separated by long highways, his characters struggle yet yearn to connect, often leaving their identities in flux. In Drive My Car, the filmmaker centers on a character submerged in grief, and only by bonding with someone else—his driver, who experiences similar feelings—can he understand and move beyond his pain. But the director sets his usual, comparatively rigid narrative structures aside for Evil Does Not Exist, reteaming with his Happy Hour cinematographer Yoshio Kitagawa to create an aesthetic that is as observant and quiet as his previous features, yet it allows more room for interpretation. Instead of following his Oscar success (a win for Best International Feature Film; nominations for Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Director) with something even more accessible or mainstream, he doubled down on his artistic interests and resolved to experiment—an admirable choice. Hamaguchi captures an astoundingly serene and beautiful world here, from forest scenes to reflective lakes that look painterly. Still, they’re not without dangers, mostly given the presence of humans.

Many critics and viewers have wondered about the title and whether or not evil really is absent from the film. Although the topic is unspoken in Evil Does Not Exist, I believe that Hamaguchi argues the concept of “evil” is a human invention that people project onto various individuals and phenomena, but it has no tangible role in the dynamics between humanity and Nature. The so-called evils perpetrated by humanity represent the behaviors of a species that exists within Nature (humans), yet, in another human construct similar to evil, people consider themselves separate from and above Nature due to their perceived intellectual superiority or religious entitlement. Therefore, many cultures feel justified in conquering Nature and, in some examples, they have made the taming of the natural world their destiny. But these notions are of human design, created to make sense of and attempt to control their world rather than coexist and achieve balance. Anything else is intrusive. At one point, Takumi notes that his grandparents first settled in the region after World War II, so the presence of people in Mizubik is relatively new. “In a way, all of us here are outsiders,” he adds. Omika, an untrained actor who worked behind the scenes as a production manager on Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, terrifically embodies Takumi’s distance from the other characters. He feels he’s being pulled in the direction of human development rather than his preferred closeness with Nature, and he rejects it with quiet certainty.

Many critics and viewers have wondered about the title and whether or not evil really is absent from the film. Although the topic is unspoken in Evil Does Not Exist, I believe that Hamaguchi argues the concept of “evil” is a human invention that people project onto various individuals and phenomena, but it has no tangible role in the dynamics between humanity and Nature. The so-called evils perpetrated by humanity represent the behaviors of a species that exists within Nature (humans), yet, in another human construct similar to evil, people consider themselves separate from and above Nature due to their perceived intellectual superiority or religious entitlement. Therefore, many cultures feel justified in conquering Nature and, in some examples, they have made the taming of the natural world their destiny. But these notions are of human design, created to make sense of and attempt to control their world rather than coexist and achieve balance. Anything else is intrusive. At one point, Takumi notes that his grandparents first settled in the region after World War II, so the presence of people in Mizubik is relatively new. “In a way, all of us here are outsiders,” he adds. Omika, an untrained actor who worked behind the scenes as a production manager on Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, terrifically embodies Takumi’s distance from the other characters. He feels he’s being pulled in the direction of human development rather than his preferred closeness with Nature, and he rejects it with quiet certainty.

Similar to the title, the cryptic finale of Evil Does Not Exist has raised questions and various interpretations. Hamaguchi has named Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Cure, 1997) as a “mentor” and cites his work as inspiration for the ending, and like most of Kurosawa’s work, the final moments could and should be read in many ways. My own interpretation follows, so skip the rest of this paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled. Coming home from school one day, Hana disappears. A search ensues and extends into the next day. Takumi and Takahashi find Hana in a field, lying dead near a gut-shot deer, known to be dangerous to humans in such a desperate state. The editing here is tricky, showing a glimpse of what happened to Hana when she approached the deer—it reacted by attacking out of self-preservation. Garbed in his garish orange wilderness clothing, Takahashi approaches, but Takumi responds with anger at what he represents—the sort of unthinking interloper who would irresponsibly shoot a deer, turning it into the dangerous animal that attacked Hana. He takes out Takahashi with a sleeper hold and then carries Hana home. The conclusion reminded me of Agnieszka Holland’s Polish thriller Spoor (2017), where a woman’s conflict with local hunters escalates into a violent climax, followed by a return to a calming oneness with Nature.

Early in Evil Does Not Exist, a scene in the parking lot of the Mizubik community center shows children playing a game of Red Light, Green Light. When “Green Light!” is announced, the children move in the same direction at once. When “Red Light!” is called, they freeze in position, creepily still. The game represents an apt metaphor for the relationship between humanity and Nature, and how humans announce social concepts that interrupt the natural flow of orderly ecosystems. People make conscious choices to stop the natural movements and progressions of the environment by settling, developing, and building on land. Their presence doesn’t have to be invasive, but no matter where humans are, they redefine the space with their technology and consume resources, often without considering sustainability or long-term effects. Evil Does Not Exist weighs this relationship from Nature’s perspective and sees the only ruptures in the natural order. While it’s reasonable for humans to use their surroundings to improve their lives, Hamaguchi’s thoughtful and patient narrative recognizes the devastation that occurs within this relationship, some of it inevitable, and much of it avoidable.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review