Reader's Choice

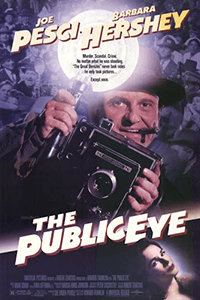

The Public Eye

By Brian Eggert |

In The Public Eye, Joe Pesci plays Leon “Bernzy” Bernstein, known among cops and the criminal underworld as the Great Bernzini. Early in the 1992 film, two sequences establish the character’s driving forces: self-interest and art. The first finds Bernzy snapping photos at crime scenes. He has a knack for getting there before the cops do. At one, Bernzy adjusts a dead body to a more dynamic angle for his picture; at another, he dresses as a priest to gain access to an ambulance and snap a photo of an axe-murderer’s victim. The second sequence finds Bernzy meeting with a photographic art publisher. When his book of New York street life is deemed too “sensational” and “vulgar” to be art, Bernzy recoils. “‘It’s a photo—let’s pretend it’s a painting,’” he mocks with contempt for the still lifes and nudes usually associated with photographic art. From these two sequences, the question at the center of writer-director Howard Franklin’s feature lies in whether Bernzy is a bottom feeder who thrives on documenting the misery of others or whether his unique perspective elevates his subjects into art. Can both be true? However intriguing the question, The Public Eye’s investigation into the nature of this opportunistic artist is secondary to the film’s mystery, which, though modeled after popular neo-noirs, never quite achieves the same level of interest.

Franklin based Bernzy on Arthur Fellig, nicknamed Weegee, the Manhattan freelance photojournalist famous for capturing New York’s visceral street life in candid black-and-white photos. Weegee’s first photo book, Naked City, debuted in 1945 and inspired Hollywood producer Mark Hellinger to develop the film The Naked City (1948), which coined the line, “There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them”—made famous on the subsequent Naked City series on ABC (1958-1963). Like Weegee, Bernzy uses a rubber stamp with a circular logo to sign his photos, establishing a personal brand of artistic authenticity that denies any association with the reputation of other vulture-like tabloid photographers in his profession. Pesci even resembles Weegee, with his short-cropped hair and puggish looks. Franklin’s original screenplay has his fictionalized Weegee investigating a conspiracy. It’s a strange premise, given that Weegee was not a detective but an artist and documenter of life on the streets. Moreover, Franklin’s mystery sidelines Bernzy’s relationship with art and commerce for a stylistic pastiche of nostalgic crime cinema in the vein of Chinatown (1974) and The Untouchables (1987).

Set during the 1940s, The Public Eye establishes Bernzy as a self-proclaimed impartial observer, with allegiances to neither the cops nor the crooks. Taking sides gets in the way of getting pictures, and he has hundreds of them. They’re categorized into boxes—with labels such as “Drunks,” “Cops,” “Hunger,” and “Murder”—in his messy apartment, signifying Bernzy’s status as a loner and outsider. A night owl, Bernzy listens to a police radio in his car and, after snapping photos of a crime scene, he processes them quickly in the homemade darkroom in his trunk, undercutting other shutterbugs to secure the few bucks he’s paid for each shocking photo. The plot kicks in when Bernzy finds himself wrapped in a conspiracy involving two warring mob factions, valuable gas rationing coupons, and Kay Levitz (Barbara Hershey), the widowed owner of the Café Society nightclub. Despite warnings from a well-informed doorman (Jared Harris) that Bernzy is a “scavenger” with “no morality,” Kay sees his artistic side. But she’s also a femme fatale of sorts, getting Bernzy into trouble with the wrong people.

A widow. A conspiracy. A bid for power and money. Indeed, Franklin borrows his structure from Chinatown—or perhaps, based on Robert Zemeckis’ role as producer, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). The filmmaker loosely ties the intrigue to the impact on American soldiers fighting abroad in World War II, but that consequence never amounts to much. Likewise, most of the characterizations prove superficial in Franklin’s hands, dependent on the production’s style over narrative substance. Kay’s genuine interest in Bernzy’s art attracts the photographer, who’s desperate for validation and, therefore, susceptible to manipulation. Pesci is strong in the lead role, which he took after earning an Oscar for Goodfellas (1990), hoping to become a leading man instead of the memorable supporting player from Raging Bull (1980) and Home Alone (1990). Bernzy is a wounded figure, confident in his art and skill but hoping for approval. Several scenes where Kay slights him show a sensitive side rarely portrayed by the actor. Hershey, meanwhile, is somewhat rigid and dry in what should be the film’s juiciest role.

Franklin wanted to explore Weegee, but he couldn’t find a way to make the character engaging enough for general audiences without placing him at the center of a labyrinthine case. A mystery is something Universal Pictures could sell; a portrait of an artist, much less so. Still, several sequences, captured in high-contrast monochrome by cinematographer Peter Suschitzky, a frequent collaborator with David Cronenberg, convey how Bernzy sees the world. Everything’s a potential photograph through Bernzy’s eyes. At times, his world moves in slow motion as he processes what’s unfolding and where he can place his camera. He’s always negotiating how to turn any situation into a work of art, and he’s loaded with cameras hidden in his pockets. While such details make for amusing quirks, they also provide an unintended parallel to people who obsessively turn their lives into social media content. Bernzy’s almost fanatical need to document everything suggests that this is not a new development in human behavior. Since technology allowed us to record the world and present it to others, we did so with almost addictive urgency. But, whereas cameras were a luxury in Weegee’s day, almost everyone has one in their pocket today.

The Public Eye never confronts Bernzy’s claim to capturing “life as it happens,” though he’s constantly manipulating reality to enhance the outcome in a manner “people like to see.” In one scene, Kay looks on as Bernzy stages a drunk passed out in a rainy alley, hoping to compose a perfect shot. In this way, Bernzy is less an observer of reality than a documentarian such as Werner Herzog, who’s not interested in a vérité aesthetic but in conveying the world through a filter Herzog calls “ecstatic truth.” This allows the observer to manipulate reality to heighten its intended meaning, which is what all documentarians and photographers do when processing the real world. They shape a story or manipulate light and composition to present reality in dramatic, evocative terms, but they’re not interested in direct cinema or its purely photographic equivalent. With Bernzy nimbly maneuvering a criminal situation in hopes of photographing the violent fallout between two warring gangs, he’s less a noble artist than one of the unscrupulous ambulance chasers from Nightcrawler (2014). However, Franklin is far less critical of this behavior than Dan Gilroy was of Lou Bloom’s (Jake Gyllenhaal) actions.

The Public Eye has a curious classicism and polish for a picture about gritty street crime, gangsters, and wartime profiteers. The production boasts all the classic cars, period-appropriate costumes, and scenery to deliver a convincing view of 1940s New York. But Suschitzky’s even-keeled camerawork and lighting feel jarringly straightforward, neither moodily presented in noirish terms nor heightened to Weegee-esque extremes. The film has the handsome look of Chinatown’s respectable sequel, The Two Jakes (1990), combined with the classy treatment of superficial details in The Untouchables. However, some visual panache, bravado, or perhaps a more kinetic, tabloid-style momentum would have better reflected the material. Instead, the tone is relatively flat and leisurely paced, and editor Evan A. Lottman never captures Bernzy’s zippy energy in the film’s measured pacing. Scenes where Bernzy cajoles his way into an FBI agent’s office or convinces a camera-shy mobster to allow a photo should crackle; instead, they just kind of happen.

Released to poor box-office receipts and mixed reviews, The Public Eye remains a competent 1990s production. Roger Ebert was among the few who gave the film his highest rating, admiring its “couple of great juicy movie performances” and comparing the result to Casablanca (1942). More akin to my take was Vincent Canby’s assessment in The New York Times that the film “never quite takes off, either as romantic melodrama or as a consideration of one very eccentric man’s means of self-expression. The facts are there, but they never add up to much.” Franklin’s career as a director never quite took off, either. He was limited to co-helming Quick Change (1990) with Bill Murray and then, after The Public Eye, overseeing the Murray-and-an-elephant road movie, Larger than Life (1996). Since then, Franklin has been working as a screenwriter on a few modest projects. And while it’s easy to give The Public Eye a pass as a competent crime thriller, Franklin fails to engage its protagonist with the complexity he deserves. The writer-director never resolves or sufficiently addresses Bernzy’s opportunistic scheming, which flies in the face of his self-proclaimed artistic integrity.

In the end, Bernzy is celebrated for exposing a gas-rationing conspiracy by way of his efforts to document a gangland shootout. He schemes and puts himself in great danger to capture the gunplay on camera, not the before or after that he usually photographs. Why is capturing that moment so important, and why now? He also secures a book deal, wrapping up the story in a tidy bow, save for his inability to stop seeing the world as one big potential photograph. The Public Eye sees Bernzy as a pure artist whose way of processing the world is what matters. However, his tactics suggest less of a keen eye for observation than an acute understanding of what the public wants to see and how to manipulate reality to achieve that. It’s a subtle distinction that never becomes a conflict for the character or the film, though it seems like a vital contradiction that could have made Bernzy that much more complicated if addressed. As it is, The Public Eye alternates between character study, artistic appreciation, and conspiracy yarn, but it never balances these individual strains into a satisfying whole.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on April 2, 2024. Thank you, Steve, for your continued support!)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review