Reader's Choice

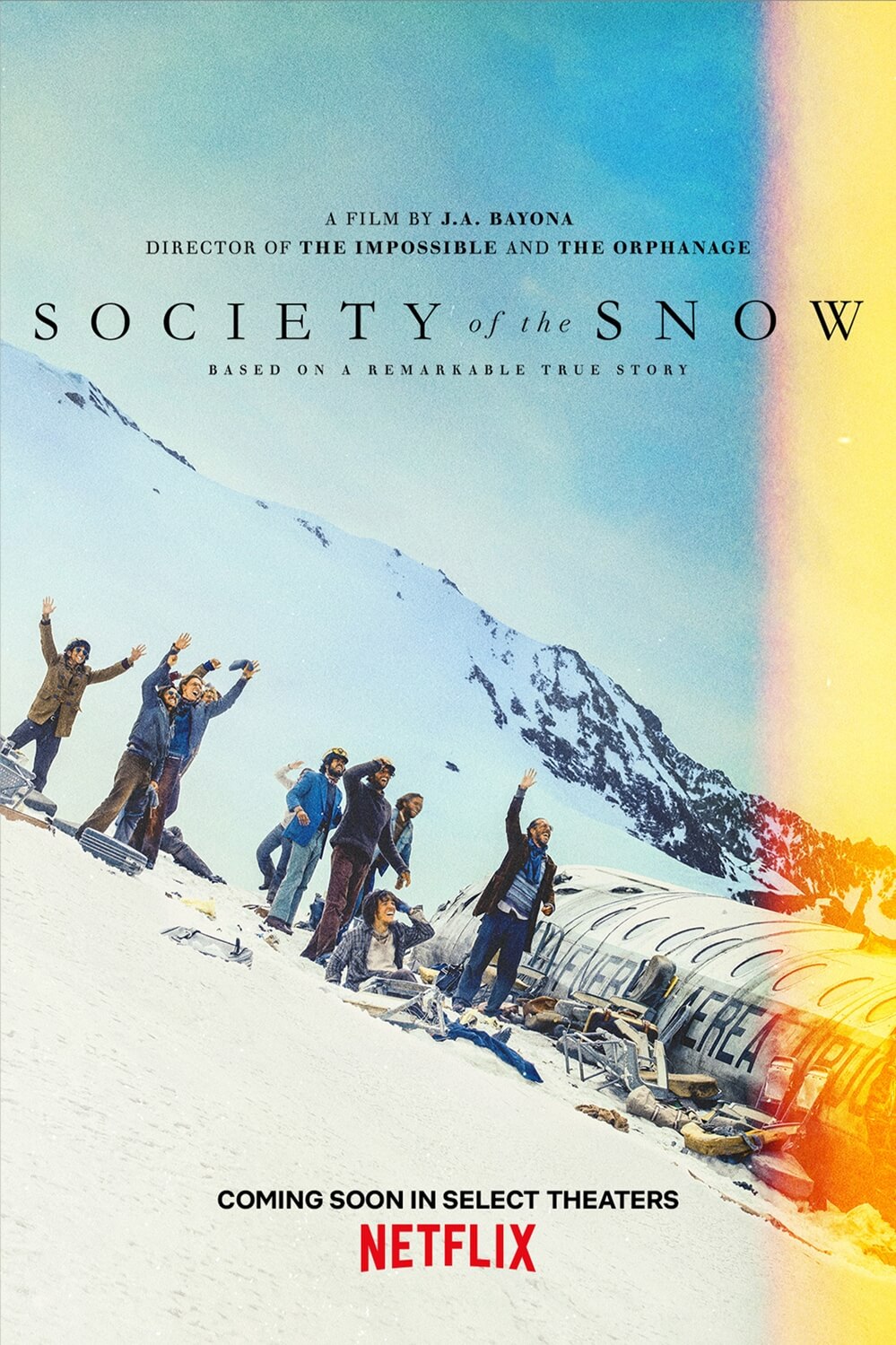

Society of the Snow

By Brian Eggert |

Society of the Snow is about the so-called Miracle of the Andes. On October 13, 1972, a plane with 45 passengers departed from Uruguay en route to Santiago, Chile, and collided with a mountain ridge in the Andes. Authorities did not discover the 16 survivors until ten weeks later. Although many members of the Old Christians rugby team on the flight would attribute their survival to a “miracle,” watching the film, it doesn’t seem like an extraordinary phenomenon inexplicable by natural or scientific laws. Instead, the survivors relied on their ingenuity, perseverance, and sheer luck, not to mention their choice to eat their dead. Fortunately, director J.A. Bayona—who’s no stranger to disaster movies after The Impossible (2012), about a family who survives the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami—doesn’t present what happened through the religious lens of a miracle. Despite Bayona’s sometimes distractingly flashy camerawork, he gives the viewer a sense of authenticity and emotional immediacy about what happened.

Bayona and his co-writers Bernat Vilaplana, Jaime Marqués, and Nicolás Casariego adapt the 2009 book La sociedad de la nieve by Pablo Vierci; though, the incident has been covered before on film. Mexican director René Cardona helmed the 1976 feature Survive!, based on the 1973 book by Clay Blair, which had a made-for-TV quality production modeled after Irwin Allen disaster movies. Hollywood also took its turn when Frank Marshall directed the 1993 version of the story, Alive, featuring a curiously American cast, including Ethan Hawke and Josh Hamilton playing Uruguayans. For a more factual experience, see the excellent 2007 documentary Stranded: I’ve Come From a Plane That Crashed on the Mountains, dramatic reenactments notwithstanding. What Bayona—who could not get a production about this story of this scope made anywhere but Netflix—brings to his production is a verisimilitude that’s missing from earlier versions, from the grislier details to the vast panoramas of the Andes (even though Spain’s Sierra Nevada mountains stand in for the Andes). Its treatment of the eventual consumption of human flesh, too, feels more frank about the choice and how it’s represented than in previous adaptations.

But the screenplay weighs down the events with clunky lines foreshadowing the crash and method of survival. The early scenes in Montevideo show several characters at church, listening to a sermon that “man cannot live by bread alone.” Later, Pancho (Valentino Alonso) convinces Numa (Enzo Vogrincic) to join their friends on the flight, suggesting, “This could be our last trip together.” On the plane, one of the passengers describes the suction effect that causes turbulence and makes flying over the Andes so treacherous. In the 13 minutes of screentime before the crash, the film also introduces several characters, and keeping track of names and faces becomes challenging. Bayona and his editors (Jaume Martí, Andrés Gil) cut back to these early scenes later to remind their audience who died. Meanwhile, Numa remains the narrator, remarking on the events even after his character dies—a moment that seems engineered for a strong reaction, but instead, it feels like a tasteless trick.

Recalling Cast Away (2000), Society of the Snow’s expertly handled crash sequence and the immediate aftermath capture the traumatic experience with visceral detail and cinematic bravado. Split-second images of crushed legs and smashed bodies give way to an even more disturbing scene, where the survivors huddle together on their first night in the sub-zero temperatures, screaming from their injuries, their terror, their fallen friends, and the cold that claims more than one of them. Bayona and the cinematographer, Pedro Luque, capture their anguish with heightened camerawork, including wide-angle lenses to give the events a disorienting feel and CGI-augmented close-ups that seem rather ostentatious for this material. Bayona’s penchant for showy visuals, evidenced in A Monster Calls (2016), also applies to later sequences when an avalanche pours in through the plane’s fuselage, burying the survivors.

Recalling Cast Away (2000), Society of the Snow’s expertly handled crash sequence and the immediate aftermath capture the traumatic experience with visceral detail and cinematic bravado. Split-second images of crushed legs and smashed bodies give way to an even more disturbing scene, where the survivors huddle together on their first night in the sub-zero temperatures, screaming from their injuries, their terror, their fallen friends, and the cold that claims more than one of them. Bayona and the cinematographer, Pedro Luque, capture their anguish with heightened camerawork, including wide-angle lenses to give the events a disorienting feel and CGI-augmented close-ups that seem rather ostentatious for this material. Bayona’s penchant for showy visuals, evidenced in A Monster Calls (2016), also applies to later sequences when an avalanche pours in through the plane’s fuselage, burying the survivors.

When the film opens, Numa’s voiceover asks, “What really happened?” Bayona presents the survivors’ decision to eat the dead passengers as grave, with the highly religious survivors weighing whether their choice is legal, if they have consent from the victims, and if their choice will earn them a trip to hell. Society of the Snow is less successful at showing the personal and physical strain of starvation, and Bayona spends too little time with the characters to make any one of them feel central to the narrative. The survivors make plans, pray, and share poetry, but there’s only a vague sense of the personalities here, with most of them emerging during the debate about whether to eat human flesh for survival. While Numa’s role as the narrator becomes a cheap device after he dies, it is Nando (Agustín Pardella) and Roberto (Matías Recalt) who prove central with their days-long trek through the Andes to Chile, leading to their eventual rescue.

There’s a moment with Nando and Roberto arriving at the top of a ridge, and both hope Chile will be visible beyond the horizon. Bayona moves the camera upward, careful not to reveal what awaits them, Chile or more mountains. It reminded me of Bayona’s debut, The Orphanage (2007), and the disturbing children’s game played in that film, which relied on anticipation and dread. Bayona captures the survivors’ desperation, often in graphic, unsettling detail, but not always with the human dimension that might give the material more weight. In the end, Society of the Snow shows what happened but prompts another question: “What does it mean?” Is there a lesson to impart here? Did they survive because of a miracle? The rationale is that the few survivors give meaning to the tragic events. But that feels like a strained attempt at an answer—any answer—when nothing can adequately explain why terrible things happen. However, the film’s attempt to reach for answers doesn’t change that Bayona has brought the most harrowing depiction of this story to the screen yet.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on January 23, 2023.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review