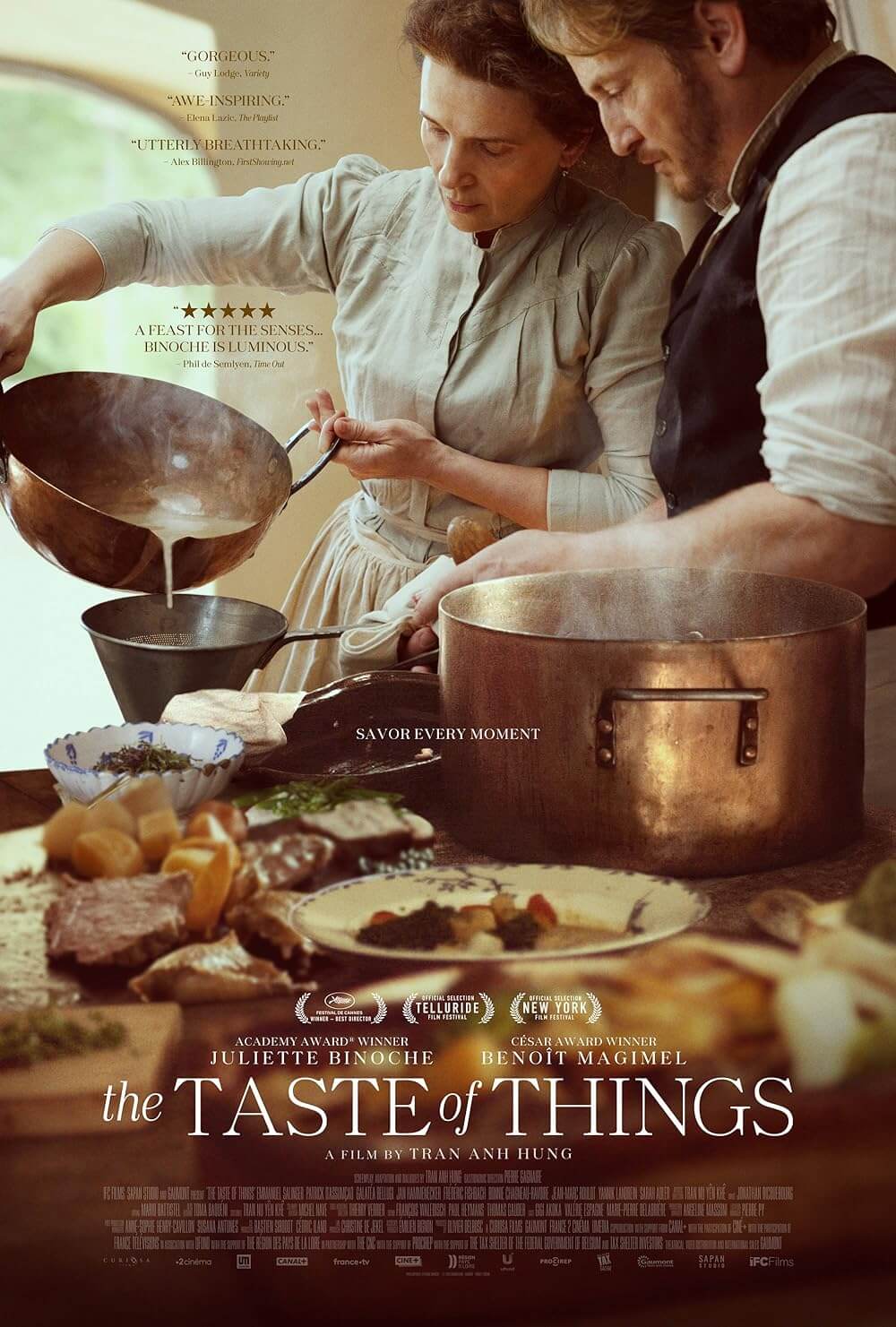

The Taste of Things

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This film was originally screened at the 2023 Twin Cities Film Fest and reviewed on October 26, 2023. Below is an expansion of the original review. The film arrives in theaters on Friday, February 9, 2024.

“What a perfect expression,” remarks a friend of Dodin Bouffant, the world-famous French chef and restaurant owner. At a regular gathering of haute cuisine connoisseurs, the friend has tasted Bouffant’s vol-au-vent—a dish that, to untrained eyes, looks like a simple bread bowl with a creamy stew inside. But the delicate pastry’s complex, rich filling includes vegetables and proteins that have taken hours to prepare. Although it’s Dodin’s recipe, his cook Eugénie has labored in the kitchen, bringing the food to life with a touch that even he cannot achieve. Without her, it’s worth questioning whether his recipes could ever be realized. This dynamic between the chef and his cook, played by Benoît Magimel and Juliette Binoche in effortlessly natural performances, is the subject of The Taste of Things, writer-director Trần Anh Hùng’s latest feature that, too, might be described as a “perfect expression.” The film belongs in the same category as Tompopo (1985) or Babette’s Feast (1987), where all elements of the cinematic apparatus have been deployed to draw out sensuous pleasures and food appreciation. But, like those other foodie films, there’s a cultivated joy involved in watching The Taste of Things, giving way to a sumptuous emotional experience that delights the senses and leaves the spectator full.

Set in 1885, the film is a moving romance and virtuosic triumph, both understated and engrossing in its portrait of a relationship that extends beyond the kitchen and into the nighttime hours when Dodin knocks at Eugénie’s door to make love. But Eugénie hesitates to marry him, despite their 20 years together. Anything not related to their refined, multilayered cuisine comes secondary. Even so, their work in the kitchen and their meals serve as conversations, communicating their relationship not in certain terms but through how Hùng observes their interplay. When we first meet Eugénie, she lovingly works in Dodin’s pastoral yet elaborate kitchen in the French countryside, where roosters and peacocks sound off in the distance. She then prepares a meal for Dodin and his inner circle of fellow gourmands (Patrick d’Assumçao, Frédéric Fisbach, Emmanuel Salinger), who wax philosophical about wine as the “intellectual side” of a meal, whereas meat and potatoes are the “material.” Savoring every bite, they take in stratified sauces and ingredients that few modern palettes could imagine or grasp—much like the film. On the periphery, there is also the young Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire), who works alongside Eugénie’s young assistant, Violette (Galatéa Bellugi), and whose refined palette suggests her future as a master chef.

The French appreciation of food could be understood by how they view cinema. Both should engage a variety of senses, evoke an array of emotions, and leave one to appreciate the artistry and dimensions involved. Hùng sought to capture this idea through his filmmaking. Having emigrated to France from Vietnam when he was 12 years old, Hùng wanted to explore what he saw as characteristic of French culture—the artistic passion and aesthetic logic applied to all endeavors. Using Marcel Rouff’s book from 1924, La Vie et La Passion de Dodin-Bouffant, Gourmet, as a springboard, Hùng’s portrait of Dodin and Eugénie’s relationship centers on food and remains true to their culinary ideals. No stranger to sensuous filmmaking—see The Scent of Green Papaya, his Oscar nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film of 1993—Hùng understands that watching ingredients come together onscreen can create a delectable sense of involuntary, mouth-watering pleasure that neither logic nor reasoning can explain. He sees beauty in the labor and process, which is a far cry from fast food or blockbuster movies.

The French appreciation of food could be understood by how they view cinema. Both should engage a variety of senses, evoke an array of emotions, and leave one to appreciate the artistry and dimensions involved. Hùng sought to capture this idea through his filmmaking. Having emigrated to France from Vietnam when he was 12 years old, Hùng wanted to explore what he saw as characteristic of French culture—the artistic passion and aesthetic logic applied to all endeavors. Using Marcel Rouff’s book from 1924, La Vie et La Passion de Dodin-Bouffant, Gourmet, as a springboard, Hùng’s portrait of Dodin and Eugénie’s relationship centers on food and remains true to their culinary ideals. No stranger to sensuous filmmaking—see The Scent of Green Papaya, his Oscar nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film of 1993—Hùng understands that watching ingredients come together onscreen can create a delectable sense of involuntary, mouth-watering pleasure that neither logic nor reasoning can explain. He sees beauty in the labor and process, which is a far cry from fast food or blockbuster movies.

The director and his cinematographer, Jonathan Ricquebourg, employ a camera that roves around Dodin’s spacious kitchen and sways amid the cook and her assistants, often in long, unbroken takes that observe each step of a recipe. With her artistry inspired by the famous chef Antonin Carême, Eugénie knows her food so well, she says, that she doesn’t even need to taste it. Whether they’re melding ingredients for an elaborate sauce, sipping wine that spent 50 years at the bottom of the sea, or sampling Baked Alaska, the food looks splendid. So do the actors’ responses to the meal. Under the supervision of French chef Pierre Gagnaire, credited as Directeur de la Gastronomie, the actors prepare actual meals. But it’s more than a cooking-show-as-cinema, even though the scenes of cooking have a certain instructional quality. While these sequences build each recipe in a transfixing progression toward the final delicacy, they also serve as an observational study of the harmony (or, evidenced later, disharmony) between the characters in Dodin’s kitchen—terrifically acted by Binoche and Magimel.

The two leads have a real-life romantic history, and perhaps they draw upon that for their performances here, which feel natural and anything but mannerist. Somewhat obscurely, in the wake of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, the Prince of Eurasia (Mhamed Arezki) calls Dodin “the Napoleon of the culinary arts,” which might make Eugénie his Joséphine. Sure enough, they have a harmonious relationship, though their association isn’t as toxic as the French Emperor’s was—it’s a harmony of artistic contributions. They both contribute to the product of their efforts. The pairing is among the most endearing couples put on screen, with Eugénie supporting their work through tireless gardening, including a new copper antennae system designed to enhance vegetable growth. She puts considerable physical effort into preparing ingredients and laboring over hot ovens and heavy pots; her exhaustion shows in fainting spells, which she dismisses as unserious. He contributes his ideas and affection, and he demonstrates his appreciation by preparing her a meal of oysters and a dessert with delicate sugar paper. The thought and energy that goes into his meals are tantamount to how he feels, and the gratitude expressed in her “merci” has boundless meaning. Still, Eugénie hesitates to marry Dodin, afraid their artistic balance may be upset by the romantic side of their relationship taking precedence.

Their devotion to their artistry, above all else, might be seen as pretentious, the antithesis of the burn-down-the-elitists message of last year’s anti-foodie thriller The Menu. However, this is contrasted by a subplot involving the Prince, who challenges Dodin to a battle of meals. The Prince’s offering is an eight-hour meal, a menu with “no line,” according to Dodin. For the French chef, a meal is not only about the quality of the food, but the journey of tastes, textures, and ideas that emerge as the meal progresses. When Dodin writes up his menu, he includes a pot-au-feu, a rustic and traditional French dish of boiled beef and vegetables normally reserved for commoners. The plan recalls Ratatouille (2007), with Remy winning over the cynical food critic Anton Ego by making the titular peasant dish, which not only conjures his sense memories from childhood but penetrates his armor. In this and the central relationship, Hùng characterizes French cuisine not as a lofty exercise in intricacy for the sake of itself, but rather, as a conversation between the chef, the person who consumes the food, and the sensations evoked by each dish. It’s a similar conversation Hùng has with his audience.

Their devotion to their artistry, above all else, might be seen as pretentious, the antithesis of the burn-down-the-elitists message of last year’s anti-foodie thriller The Menu. However, this is contrasted by a subplot involving the Prince, who challenges Dodin to a battle of meals. The Prince’s offering is an eight-hour meal, a menu with “no line,” according to Dodin. For the French chef, a meal is not only about the quality of the food, but the journey of tastes, textures, and ideas that emerge as the meal progresses. When Dodin writes up his menu, he includes a pot-au-feu, a rustic and traditional French dish of boiled beef and vegetables normally reserved for commoners. The plan recalls Ratatouille (2007), with Remy winning over the cynical food critic Anton Ego by making the titular peasant dish, which not only conjures his sense memories from childhood but penetrates his armor. In this and the central relationship, Hùng characterizes French cuisine not as a lofty exercise in intricacy for the sake of itself, but rather, as a conversation between the chef, the person who consumes the food, and the sensations evoked by each dish. It’s a similar conversation Hùng has with his audience.

Shot in the castle commune of Segré-en-Anjou Bleu, Hùng’s film immerses the viewer in a sensuous cinematic experience, producing phantom smells, tastes, and sensations. The experience amounts to the multilayered foodie concept of umami, Japan’s so-called essence of deliciousness. Even scenes outside of the kitchen have a rhapsodic yummy pleasure, such as simple scenes of Binoche picking vegetables in the garden or the shyly romantic way Dodin enters her room to find her bathing. All the while, Hùng’s approach to the camera recalls the subtle, flowing movements of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s frame in Flowers of Shanghai (1998), hypnotically moving from one corner of the scene to another in delirious pleasure, while transporting the viewer to another time and place—the natural light peering in through the windows, giving the kitchen scenes a golden sense of wonder. Each image recalls the textured beauty of a Pieter Aertsen or Joachim Beuckelaer painting, and indeed, every frame of The Taste of Things looks intentional and masterfully composed. And while it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the cooking and gorgeous imagery, every meal helps us further understand Dodin and Eugénie’s unique romance and its eventual end. Hùng’s direction left me the cinematic equivalent of food drunk.

An exquisite and quietly sophisticated feature, The Taste of Things debuted at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where Hùng won the Best Director award. There, it was called La Passion de Dodin Bouffant, before changing its name to The Pot-au-Feu. Doubtlessly too obscure for non-French audiences who didn’t grow up eating this common recipe, the apt title changed to The Taste of Things under US distributor IFC Films and will represent France’s bid for the Best International Feature Film at the 96th Academy Awards, surprisingly, over Justine Triet’s Palm d’Or-winner Anatomy of a Fall. Although many have questioned why, the reasons are obvious to this critic; it’s a far superior film. Certainly, foodie and Francophiles alike will melt in its richness, which does not limit itself to a cuisine-as-language thesis. The film is far more dimensional. Much like the paintings of Aertsen and Beuckelaer, whose vibrant market scenes have a subtle air of death about them, The Taste of Things also mourns when a great artist passes, and recognizes the patience and skill it will require to replace her. Filled with creative drive and a yearning for personal expression—and the emotions that spring from them—this is an uncommonly sublime film and a testament to the ephemeral quality of art, food, and love.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review