The Iron Claw

By Brian Eggert |

The Iron Claw opens in the early 1960s, with Texas family paterfamilias Fritz Von Erich winning a wrestling match thanks to his signature vise grip described in the movie’s title. Afterward, his two young boys and deeply religious wife meet him outside the small stadium, where he shows them their brand-new family car, an expense they cannot afford. The patriarch claims he’s “almost there” in his wrestling career and promises to leave behind the so-called curse that has followed the Von Erich family. The boys soak up every word, convinced their family’s legacy and success reside in professional wrestling. Their father wouldn’t have it any other way. In Sean Durkin’s film about the real-life Von Erichs, the writer-director considers how one man’s obsession with the American Dream is his family’s undoing—not because of a family curse or even a self-fulfilling prophecy but because, in his domineering toxicity and dogmatic fixation on wrestling, he refuses to see his children as anything but reflections of himself. If they are not the strongest, fastest, and best, they are nothing; he is nothing. The unfulfillable expectation leads to devastation, not for the father, but for his hero-worshiping sons whose lives become collateral in their father’s pursuit of greatness.

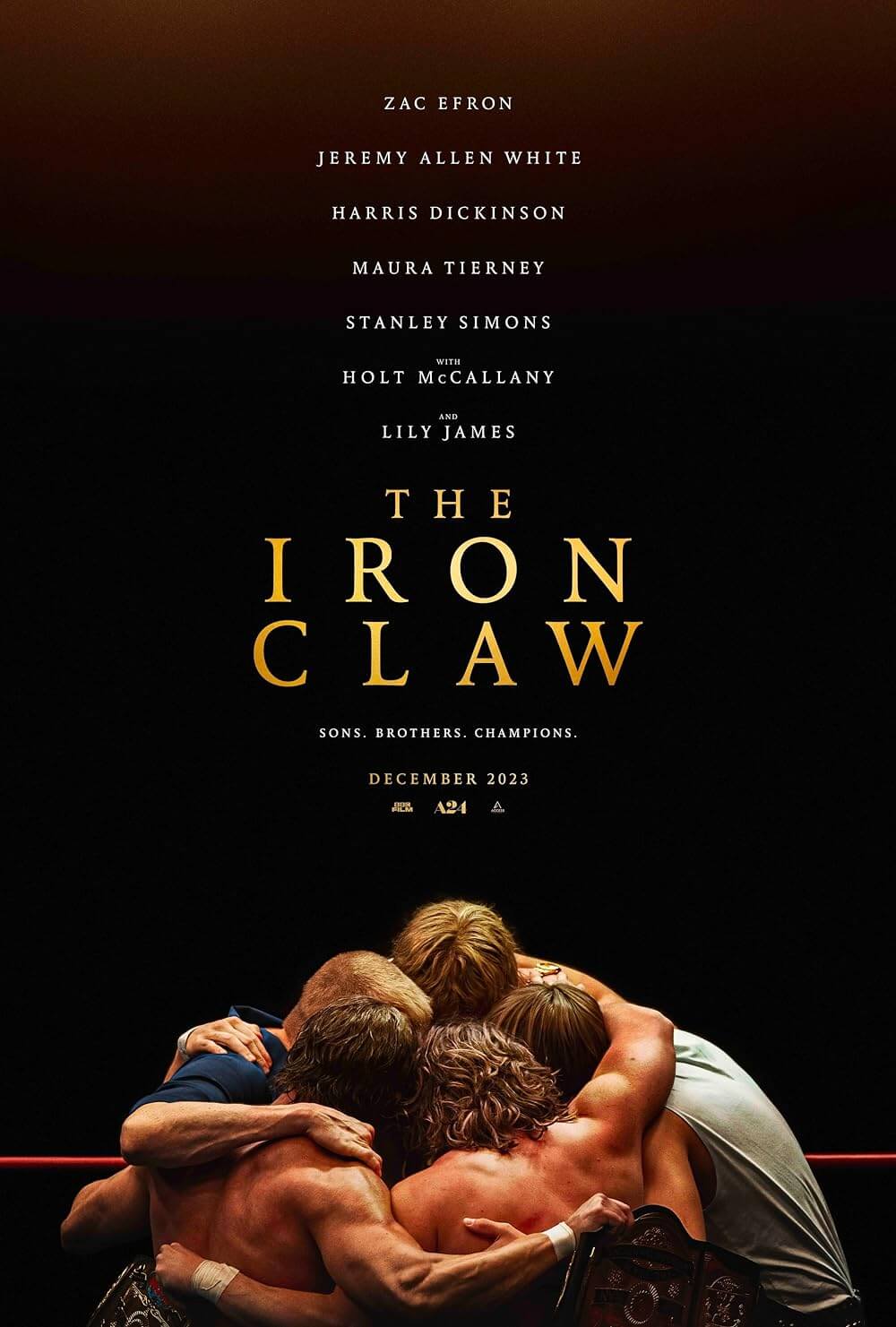

On the surface, a Von Erich family biopic is a curious topic for an A24 release by Durkin. However, professional wrestling fans of the late 1970s era and beyond, familiar with the inconceivably bleak Von Erich story, could no doubt see why the material makes such a fine pairing of filmmaker and subject. Durkin, a longtime wrestling fan, considers this story a passion project; given his earlier work, it’s easy to see why. For instance, Durkin’s debut film, Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011), deals with the unshakable psychological effects a cult has on the brainwashed main character. His next film, The Nest (2020), an overlooked marvel, investigates a self-destructive need to succeed and, if not, project an air of success. Considering those two films, The Iron Claw seems like a natural progression that combines his previously explored themes. To be sure, the Von Erich family has an almost cultish devotion to their patriarch, played with intimidating force by Holt McCallany, whose obsession with his particular definition of success derails his entire family.

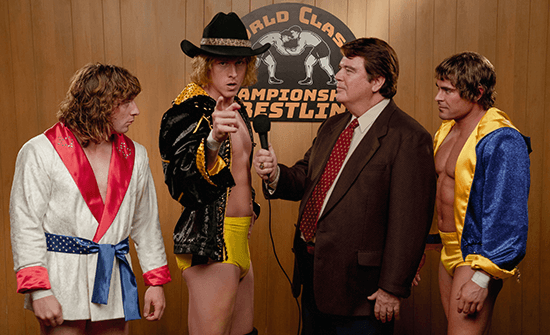

Durkin’s superbly crafted and acted film revolves around Kevin (Zac Efron), Fritz’s oldest living son. Kevin is a Dallas celebrity with his He-Man haircut and physique, wrestling in local matches arranged by his promoter father. The Von Erichs live together on a farm, protecting themselves from the family curse with their physical strength and their mother Doris’ (Maura Tierney) devotional beliefs. Although he’s the most well-known wrestler, Kevin walks the walk better than he talks the talk. His younger brother David (Harris Dickinson) has a better handle on showmanship and trash talk, a crucial aspect of wrestling. Even Kerry (Jeremy Allen White), who was set to be an Olympic discus thrower until the US refused to participate in the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow to protest against the Soviets, has a wild-man presence in the ring that serves him well. Meanwhile, their youngest brother, Mike (Stanley Simons), doesn’t have the wrestling bug; he’s a budding musician, drawing his musical skill from his father, who has suppressed his abilities with multiple instruments in favor of physical pursuits and therefore does not acknowledge Mike’s musicality.

Durkin’s superbly crafted and acted film revolves around Kevin (Zac Efron), Fritz’s oldest living son. Kevin is a Dallas celebrity with his He-Man haircut and physique, wrestling in local matches arranged by his promoter father. The Von Erichs live together on a farm, protecting themselves from the family curse with their physical strength and their mother Doris’ (Maura Tierney) devotional beliefs. Although he’s the most well-known wrestler, Kevin walks the walk better than he talks the talk. His younger brother David (Harris Dickinson) has a better handle on showmanship and trash talk, a crucial aspect of wrestling. Even Kerry (Jeremy Allen White), who was set to be an Olympic discus thrower until the US refused to participate in the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow to protest against the Soviets, has a wild-man presence in the ring that serves him well. Meanwhile, their youngest brother, Mike (Stanley Simons), doesn’t have the wrestling bug; he’s a budding musician, drawing his musical skill from his father, who has suppressed his abilities with multiple instruments in favor of physical pursuits and therefore does not acknowledge Mike’s musicality.

Durkin’s observant writing captures an aching, increasingly unhealthy family dynamic. Ever listening to their father’s expectations and orders, the brothers compete to be number one in his dinner table ranking of favorite sons. “The rankings can always change,” Fritz warns. “Everyone can work their way up or down.” Despite their competition, the brothers have a tender and supportive bond, giving each other what their parents offer only in tough love or, in their mother’s case, distanced stoicism. They fight for each other, but not against the one person they should be fighting: their father. When the sensitive Kevin asks his mother to defend Mike against their father’s bullying, she refuses to discuss it. Everything comes secondary to Fritz’s ambition to earn a “Worlds Heavyweight Champion” belt, which, even if acquired by one of his sons, would be his victory. “I’ve waited my whole life to have that belt,” he tells them. This goal overshadows his sons’ physical health and emotional needs in scene after scene, from Fritz refusing to show sympathy for Kevin’s injuries with a “walk it off” attitude to his shocking discussion of the next title match on the same day he buries one of his children.

Efron has earned attention for his bodily transformation to play Kevin Von Erich, which goes beyond looking the part into a realm of uncanniness. His beefcake appearance might even be distracting for some since before-and-after photos show a staggering amount of bulking and other physical changes. But his career-best performance has a quiet sensitivity that emerges with Kevin’s brothers and Pam (Lily James), the woman who loves him. Alas, a significantly underdeveloped aspect of Durkin’s script is Pam, who arrives in Kevin’s life and provides him with everything he might need to achieve happiness. Durkin doesn’t explore her background, and her personality feels limited to a supporting wife and mother role. Still, her idyllic presence—inhabited by James in a familiar role for her—underscores how Kevin remains driven by his father’s expectations first. The acting throughout The Iron Claw is outstanding, best seen in McCallany’s Fritz, a cruel and singular no-weaknesses character; White’s Kerry, a broken force attempting to manage his pain with self-destructive behavior; and Tierney’s Doris, a compartmentalizer who realizes late that she has suppressed far too much to appease her husband.

Having little foreknowledge about what exactly happened to the Von Erichs, not to mention little interest in the sport of wrestling, The Iron Claw played like a miserable procession of disasters for me, albeit a terrifically made one. Durkin shows some of how the wrestlers work out the moves, dramatic beats, and victory beforehand, but the film inadequately addresses how and why surprises occur in the ring. After a match, sometimes there’s bad blood; sometimes there’s chummy camaraderie to follow the braggadocious antics of Ric Flair (Aaron Dean Eisenberg). I confess to not grasping the relationship between performance and sport in wrestling, and the film offers no clarity for something wrestling fans seem to accept. Even so, the wrestling matches are shot by cinematographer Mátyás Erdély with earthy colors and evocative light, with involving and intimate choreography that stirred even this wrestling novice. Without discussing what happens to the brothers here, in case you’re unfamiliar, the series of events—from illnesses to accidents—goes from bad luck to a possible curse and, ultimately, becomes a mirror of their father’s single-minded ambitions and love that’s conditional on success.

Having little foreknowledge about what exactly happened to the Von Erichs, not to mention little interest in the sport of wrestling, The Iron Claw played like a miserable procession of disasters for me, albeit a terrifically made one. Durkin shows some of how the wrestlers work out the moves, dramatic beats, and victory beforehand, but the film inadequately addresses how and why surprises occur in the ring. After a match, sometimes there’s bad blood; sometimes there’s chummy camaraderie to follow the braggadocious antics of Ric Flair (Aaron Dean Eisenberg). I confess to not grasping the relationship between performance and sport in wrestling, and the film offers no clarity for something wrestling fans seem to accept. Even so, the wrestling matches are shot by cinematographer Mátyás Erdély with earthy colors and evocative light, with involving and intimate choreography that stirred even this wrestling novice. Without discussing what happens to the brothers here, in case you’re unfamiliar, the series of events—from illnesses to accidents—goes from bad luck to a possible curse and, ultimately, becomes a mirror of their father’s single-minded ambitions and love that’s conditional on success.

Durkin’s portrait of the Von Erichs follows the structure of a Greek tragedy until the marginally uplifting final scenes. But even these are bittersweet moments, alternating between a grounded view of the afterlife—hinted at throughout the film, and the only haven the brothers could find from their father—and a happily ever after scene that shows how Kevin will forever wrestle with father-son relationships. Along the way, some of the individual brothers remain underdeveloped and more compelling for their role in the family than as individuals. Still, their fates are no less shattering to behold. Through Kevin’s perspective, Efron commands the film, sharing chemistry with James and a wounded quality that makes his scenes with the other family members feel rich with emotional complications. But more than any one performance, The Iron Claw is best when grappling with the family’s dogged belief that masculinity is strength, emotions mean weakness, and only the best is good enough. When those ideas prove to be false, the family is ill-equipped to process their grief and disappointment, and Durkin mines their delusions for a powerful American tragedy.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review