The Boy and the Heron

By Brian Eggert |

Returning to feature-length animation after a supposed retirement, Japan’s premier animator, Hayao Miyazaki, demonstrates why he’s an absolute original with his new film, The Boy and the Heron. It’s another transportive wonder, filled with imaginative ideas and bizarre characters who sometimes defy understanding. He contains them within a circuitous narrative that takes its young hero into a fantasy realm, where the story continues down a labyrinthine path before doubling over on itself. “My, a lot of strange things happen in this place,” observes a character. “So many things.” That’s true enough; the film is loaded with bizarre creatures and astonishing magic. The dreamier surroundings mark a return to storybook escapism after his last picture, The Wind Rises (2014), a rather grounded story steeped in Miyazaki’s interest in aeronautics, Japanese history, and early life around his father’s airplane parts company. The Boy and the Heron follows the tradition of the filmmaker’s most celebrated works, journeying into another world where entrenched themes of self-discovery materialize. That he combines his searching narratives with such creativity and vision is what makes Miyazaki’s films exceptional.

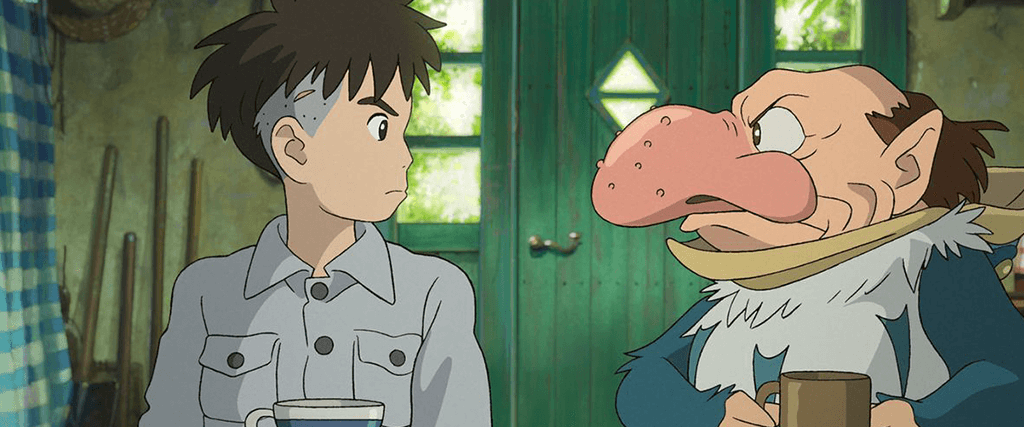

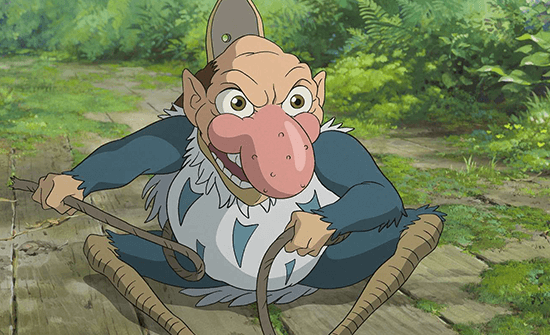

The story begins three years into World War II when a hospital fire claims the life of Mahito’s mother. A year later, Mahito’s father Shoichi gets remarried—to his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko—and moves their family into the country, near his munitions factory. There, overseen by a grotesque gaggle of old maids, Mahito escapes his loneliness and bullying at school by following a mysterious gray heron. The bird seems to beckon him (“Mahito, save me!”), while also revealing a pocky nose and human teeth within its beak—the signs of a magical figure in a bird suit, known only as The Grey Heron. Eventually, Mahito follows the bird into a nearby ramshackle home built by his mother’s eccentric uncle, who amassed an exhaustive library. Inside, the boy stumbles upon, or more accurately dissolves into, another dimension of magic and phantoms, fire-throwing sailors, voracious pelicans, and parakeet soldiers hungry for human flesh, and, eventually, takes a trippy voyage through space and time to meet an all-powerful sorcerer—his Granduncle, who oversees the literal building blocks of the universe. In the end, everyone returns to their reality safely, if covered in bird shit.

Miyazaki enthusiasts the world over will recognize his familiar preoccupations: children taken to the countryside where they discover something fantastical; intrepid female characters; self-reliant pirates; war-mongering villains; cute pouf creatures that move in dreamlike waves; vast, painterly landscapes; and questions about what the future holds. I will admit to feeling somewhat confused in the film’s second half, struggling to understand the dynamic between Mahito’s all-knowing Granduncle and the militarized Parakeet King. Some fast-and-loose world-building around Corridors of Time and a Stone of Power should probably go unquestioned and be accepted as abstract concepts, but I found them distractingly unclear. More than other Miyazaki films, The Boy and the Heron deals with out-there concepts. Trying to box those ideas into a cohesive, logical fantasy is tempting. But it’s also exactly what Mahito and the viewer shouldn’t do—a theme that becomes apparent by the finale, and which, perhaps after another viewing, I will probably be able to accept without pause.

The film’s Japanese title, How Do You Live?, shares its name with the 1937 novel by Genzaburō Yoshino, which makes a brief but crucial appearance in the film. Yoshino no doubt inspired Miyazaki. In 1931, a government-ordered branch of Tokyo’s police force, determined to squash any anti-authoritarian messages in artistic expression, imprisoned Yoshino for his socialist ties and thinking. His time in prison only emboldened his feelings. Upon his release 18 months later, Iwanami Shoten Publishers asked him to contribute a series of books to encourage free thinking and the humanities among Japanese youth. Although the publishers wanted a textbook, Yoshino’s position was unambiguous and might’ve drawn unwanted attention, so his editor suggested that he write a more equivocal novel instead. The subversive result is a coming-of-age story that follows a boy in Tokyo after his father’s death. The perspective shifts from the boy to his uncle in a series of letters, which, in the end, pose the titular question. Although Imperialist Japan banned the book in 1942, it reemerged after the war and became a cultural touchstone, selling over two million copies—at least one of them to Miyazaki.

The film’s Japanese title, How Do You Live?, shares its name with the 1937 novel by Genzaburō Yoshino, which makes a brief but crucial appearance in the film. Yoshino no doubt inspired Miyazaki. In 1931, a government-ordered branch of Tokyo’s police force, determined to squash any anti-authoritarian messages in artistic expression, imprisoned Yoshino for his socialist ties and thinking. His time in prison only emboldened his feelings. Upon his release 18 months later, Iwanami Shoten Publishers asked him to contribute a series of books to encourage free thinking and the humanities among Japanese youth. Although the publishers wanted a textbook, Yoshino’s position was unambiguous and might’ve drawn unwanted attention, so his editor suggested that he write a more equivocal novel instead. The subversive result is a coming-of-age story that follows a boy in Tokyo after his father’s death. The perspective shifts from the boy to his uncle in a series of letters, which, in the end, pose the titular question. Although Imperialist Japan banned the book in 1942, it reemerged after the war and became a cultural touchstone, selling over two million copies—at least one of them to Miyazaki.

On the surface, The Boy and the Heron doesn’t bear much resemblance to the book, except, by the film’s end, they both contain a message that life isn’t about controlling the universe; it’s about appreciating art and the people around you. Miyazaki occasionally tells stories featuring despots who try to conquer Nature or a kingdom in the name of power—see Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997), and Ponyo (2008)—and sometimes finds they regret their actions. His latest film contains that message as well. However, the Granduncle remains an underdeveloped character and hardly a cruel ruler, while the Parakeet King is hungry for power and control. The book’s theme, originally meant to remark on the tyrannical leaders of World War II, feels ever more germane for a world once again facing fascistic leaders and dictatorships. And so, given the ubiquitousness of Yoshino’s book and Miyazaki’s name, Studio Ghibli didn’t bother advertising The Boy and the Heron in Japan. The filmmaker is so renowned that they only needed to release a poster for it to become the country’s highest-grossing film of 2023.

The film delivers on most levels that the writer-director’s fans have come to expect, not the least of which is gorgeous animation. Working in a hand-painted style, Miyazaki’s imagery is boundless—from swarms of frogs and fish chanting “Join us” to the nightmares of fire and ash that preoccupy Mahito’s subconscious, the film is stunning. Only a few computer-aided pans across painted stills create a jarringly unnatural effect. After years without a new Miyazaki film, having to endure one empty computer-animated Dreamworks or Illumination product after another, it’s a treat to be back in Miyazaki’s mind and cinematic arena again. In this familiar visual space, the brushstrokes on trees are visible, the characters have a never-seen-anything-like-it quality, and the overall aesthetic is contemplative. This is also a quiet film, filled with long passages of silence and visual storytelling, only occasionally aided by longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi’s delicate score.

Since the film shares so much substance with many other Miyazaki works, it’s tempting to measure The Boy and the Heron against them. But how do you compare a director’s work when he’s responsible for so many masterpieces, and should you? The process would be unfair, yet I must admit this film would rank toward the bottom half of his output for me. I wasn’t filled with the same degree of wonder as I was with My Neighbor Totoro (1988); the protagonist’s adventure of self-discovery wasn’t as compelling as the one in Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989); I wasn’t as enrapt in the forward thrust of the narrative as I was with Princess Mononoke; the logic and rules of this fantasy world, overseen by an all-powerful creator, weren’t as cogent as those in Spirited Away (2001) or Ponyo. Even so, The Boy and the Heron extracts thematic inspiration from these films; however, maybe those concepts are so ingrained in Miyazaki at this point that they’re less self-referential than variations on career-long themes. Either way, the result feels like a more appropriate final film than The Wind Rises, should it be the 82-year-old filmmaker’s last. Let’s hope it isn’t.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on December 13, 2023.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review