Ferrari

By Brian Eggert |

Michael Mann makes movies about professional men. Thieves, cops, hackers, TV news producers, or hitmen—they’re the best at what they do. Whatever their field, their vocation comes first. Nothing comes between them and a well-executed job—not family, personal happiness, or, in some cases, even morality. Enzo Ferrari believed in his brand of mechanically sound fast cars, designed with a commitment to style that reflected Italian high couture. An early scene in Mann’s Ferrari finds the auto impresario, played by Adam Driver, standing for photos next to his new driver, Alfonso de Portago (Gabriel Leone), whose movie star girlfriend Linda Christian (Sarah Gadon) sits on the car’s company logo. Enzo reaches over and scoots her closer, not to be nearer to the starlet, which is what she doubtlessly thinks, but to get the brand in the shot. But beyond his iron will exterior, Enzo Ferrari is an archetypal Mann protagonist, meaning there’s a deep wound he’s protecting behind that composed exterior. However characteristic Ferrari may be of Mann’s thematic preoccupations, the storytelling isn’t as compelling as the director’s other subjects; though, there’s enough here in terms of complex characters and expert racing scenes to mildly recommend it.

Mann has been developing Ferrari as a passion project for over twenty years. He eventually realized the production outside of usual channels—generally, his career has been situated in Hollywood—having been burned by studio interference on his last picture, Blackhat (2015). For Ferrari, the $95 million project received independent financing and distribution from a relatively small studio, Neon, affording the auteur freedom to maneuver. But there’s something about filmmakers who spend decades conceiving and developing a property, only to finally see it realized, that they falter when the time comes to shoot the thing. Martin Scorsese had wanted to make Gangs of New York (2002) for thirty years before finally shooting the project under the interfering producer Harvey Weinstein, and the disappointing result is far from the director’s best. After completing his dream project with 2004’s underwhelming Alexander, Oliver Stone continued to tinker with the film, producing three alternate cuts for home video, none of which resolved the epic’s problems. Similarly, there’s greatness in the idea of an Enzo Ferrari biopic, but Mann’s film suffers from languid pacing in the first half and a central performance that, while skilled, is distractingly miscast.

Written before he died in 2009, Troy Kennedy Martin’s screenplay draws from Brock Yates’ 1991 book, Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, and narrows the story to a few months in 1957 that distill Ferrari’s identity through a personal and professional collision. The screen story builds toward the Mille Miglia, the once-famous race that began in Rome and lasted “1,000 miles” through cities, valleys, and the countryside. Winning the race becomes essential to restoring Enzo’s professional glory, which is threatened by his company’s shaky solvency and rivals from Maserati. At home, Enzo clashes with Laura (Penélope Cruz), his wife of more than twenty years, who helped him start the company and mothered the child they lost to muscular dystrophy. In a location he went to considerable lengths to keep secret from Laura, Enzo maintains a relationship with Lina (Shailene Woodley), whom he met during the war. Their 12-year-old son, Piero (Giuseppe Festinese), could become the heir to Ferrari—a successor and conveying power through lineage remains a kingly concern for the protagonist.

Written before he died in 2009, Troy Kennedy Martin’s screenplay draws from Brock Yates’ 1991 book, Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, and narrows the story to a few months in 1957 that distill Ferrari’s identity through a personal and professional collision. The screen story builds toward the Mille Miglia, the once-famous race that began in Rome and lasted “1,000 miles” through cities, valleys, and the countryside. Winning the race becomes essential to restoring Enzo’s professional glory, which is threatened by his company’s shaky solvency and rivals from Maserati. At home, Enzo clashes with Laura (Penélope Cruz), his wife of more than twenty years, who helped him start the company and mothered the child they lost to muscular dystrophy. In a location he went to considerable lengths to keep secret from Laura, Enzo maintains a relationship with Lina (Shailene Woodley), whom he met during the war. Their 12-year-old son, Piero (Giuseppe Festinese), could become the heir to Ferrari—a successor and conveying power through lineage remains a kingly concern for the protagonist.

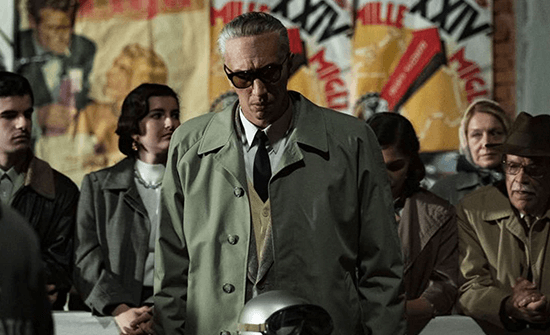

Mann builds tension toward both the climactic race and the clash between Enzo’s dual families by emphasizing the theme that, as he explains to both his team at Ferrari and his son, “two objects to occupy the same space.” Whether applied to race car drivers on the course, the market of high-end luxury car companies, or the women in his life, the outcome is the same: someone has to go. Dramatically, it’s tragic that Enzo is aware of this fact and is strategic about it when he has racing and his business in mind, yet he fails to recognize the personal implications. Mann is persistently fascinated by Enzo’s shrewd tactics as a businessman, and he actively challenges our empathy with the character’s steely exterior. However, a few carefully placed moments hint at the tender person beneath his sunglasses-at-night persona. A sequence early in Ferrari finds Enzo and Laura passing each other on individual visits to the family tomb to visit their son. There, alone, Enzo allows himself to break down. Moments of passion occur with Laura and Linda, but more often, he’s moving through domestic spaces with a preoccupied urgency.

Despite the cast performing in English with Italian accents, Ferrari never devolves into the almost parodic experience of 2021’s House of Gucci, also starring Driver. But the lead’s accent tests the limits of credibility. Still, casting the 39-year-old actor may not have been the most convincing choice since the make-up department had to age Driver up by twenty years to play Enzo. My eyes kept going to that indent on Driver’s forehead, where the actor’s real hair hides beneath the false skin used for Enzo’s receding hairline. (More effective is Patrick Dempsey’s ghost-white coif as Piero Taruffi, one of Ferrari’s racers.) These concerns are purely visual, given Driver’s skill at playing husbands with fractured personal and professional lives (see 2019’s Marriage Story, 2021’s Annette, or 2022’s White Noise). But the other actors Mann considered for the role—Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman—feel equally misguided. In any case, Cruz is more appropriately cast, playing a fiery and unapologetic force of energy, ever willing to confront Enzo about his lies and personal failures.

Mann works with Mank (2020) and The Killer (2023) cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt to craft a sleek, stylish presentation. Production designer Maria Djurkovic and costume designer Massimo Cantini Parrini load the screen with small details that car enthusiasts will probably appreciate, delivering the kind of film that will earn awards attention for technical categories. The racing sequences don’t dominate the movie as they do in Ford v Ferrari (2019). But they’re composed with a striking visuality of bright red cars penetrating the pale green landscapes. Given the length of the race, the finale doesn’t feature a moment-to-moment accounting of who’s ahead, so it doesn’t feel immersive. And since Ferrari has five cars on the track, it’s difficult to keep track of who’s where, unlike in Ford v Ferrari’s solo driver setup. Yet, Mann captures how fast they’re going to queasy effect, leaving longtime Ridley Scott editor Pietro Scalia to punctuate driving scenes with gasp-inducing crash sequences that convey the horrific nature of high-speed automobile disasters.

Mann works with Mank (2020) and The Killer (2023) cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt to craft a sleek, stylish presentation. Production designer Maria Djurkovic and costume designer Massimo Cantini Parrini load the screen with small details that car enthusiasts will probably appreciate, delivering the kind of film that will earn awards attention for technical categories. The racing sequences don’t dominate the movie as they do in Ford v Ferrari (2019). But they’re composed with a striking visuality of bright red cars penetrating the pale green landscapes. Given the length of the race, the finale doesn’t feature a moment-to-moment accounting of who’s ahead, so it doesn’t feel immersive. And since Ferrari has five cars on the track, it’s difficult to keep track of who’s where, unlike in Ford v Ferrari’s solo driver setup. Yet, Mann captures how fast they’re going to queasy effect, leaving longtime Ridley Scott editor Pietro Scalia to punctuate driving scenes with gasp-inducing crash sequences that convey the horrific nature of high-speed automobile disasters.

Mann’s modern-day crime stories, such as Thief (1981), Heat (1995), and Blackhat tend to resonate more with me and feel more appropriate with his particular aesthetics than his uneven period pieces, including The Last of the Mohicans (1992), Ali (2001), and Public Enemies (2009). (The outlier is his masterful look at contemporary news television in 1999’s The Insider, a bona fide masterpiece, and increasingly my favorite of his films.) Ferrari is a typical Mann period drama in that it feels trapped between classicism and modernity. Watch the opening sequence, shot to look like black-and-white prewar footage of Enzo racing a car. The footage cuts several times, even employing a close-up, which would be impossible in that vintage footage situation. It’s a flourish that feels discomfiting, even indulgent in this context. Individual moments such as the two crashes or any scene with Cruz feel alive, whereas others feel cold or simply uneasy due to Driver’s ill-fitting presence. This is an actor whom I admire, and who I would call one of the finest working today, but his presence never dissolves into the mise-en-scène, making Ferrari an experience of constantly trying to reconcile Driver and Mann’s choices. While it’s easy to appreciate the technical and even thematic craftsmanship that went into some areas, others, such as Driver’s makeup and accent, feel awkwardly applied, and I never quite settled into the experience.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review