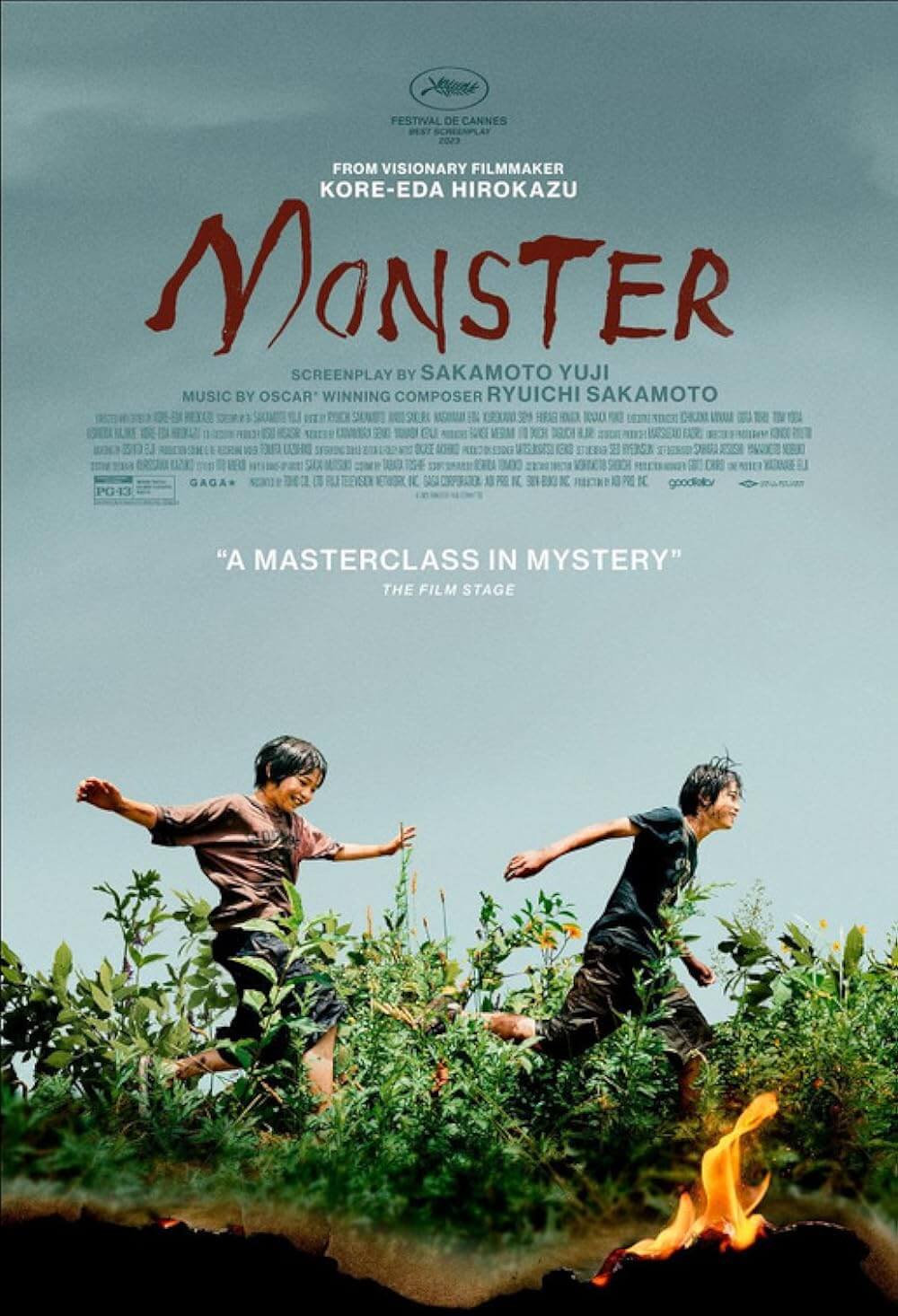

Monster

By Brian Eggert |

In his 1939 masterpiece The Rules of the Game, Jean Renoir’s character Octave remarks, “You know, in this world, there’s one thing that is terrible, and that is that everyone has his reasons.” Our failure to understand that is the titular boogeyman at the center of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Monster, about a cross-section of humanity incapable of seeing beyond surfaces that confirm our worst assumptions. Ever the astute observer of complex family relationships, Kore-eda (Shoplifters, Still Walking) looks at troubled children, protective but misguided parents, and powerless teachers incapable or unwilling to understand what motivates others. But the Japanese drama also acknowledges that some behaviors are pointlessly cruel, spurred by an evil impulse or ingrained prejudice. Consider a brief but critical moment in Monster that follows children playing in a grocery store, loudly laughing and running. One kid runs behind an older woman, who casually extends her leg back to trip the child. Then she notices a fellow shopper saw the entire scene. Rather than react with shame or apologize, she nods her head and continues shopping. Some people’s reasons remain inscrutable.

The first scenes involve a fire at a hostess bar, a dive where lonely businessmen can find the company of a woman for hire. Single mother Saori (Sakura Ando) and her son Minato (Soya Kurokawa) watch the place burn from the safe distance of their apartment balcony. She soon learns that her son’s teacher, Mr. Hori (Eita Nagayama), regularly sees a girl from the hostess bar, and that tells her everything she needs to know about him. When Minato later accuses Mr. Hori of bullying him—saying Minato has a pig brain and even causing physical harm—Saori takes the issue to the principal, Makiko (Yūko Tanaka). Saori has also heard some disturbing news about the principal, that her husband accidentally backed over their grandchild, and she has been grieving. In her exchanges with the school staff about Mr. Hori’s conduct, Saori receives flat, bureaucratic responses to her complaints, clearly crafted by the school’s lawyers: “We accept your opinion with seriousness,” et cetera, et cetera. Their and Mr. Hori’s apologies seem rehearsed, yet the defiant teacher can barely hold back what seems to Saori like a cruel laugh.

But then Monster shifts from Saori’s perspective to Mr. Hori’s, who’s regularly mocked by his hostess lover for his awkward smile and told by the school’s management that he’s “shifty-eyed and suspicious.” What happens to a person when they’re constantly told their appearance is off-putting? Replaying some of the earlier events and shedding light on others, we see that Minato’s accusations may not be true. There’s something more involved going on, and it includes Minato’s fellow student, Yori (Hinata Hiiragi), whose father (Shidō Nakamura) is an abusive drunk and calls Yori a “monster.” We also learn the origin of the “pig brain” insult and a song Minato sings with the refrain, “Who is the monster?” There’s a small collection of presumptions that the viewer makes based on what Kore-eda decides to show us, such as who may have set fire to the hostess bar, who killed a dead cat found near the school, or who was bullying whom. The director and his cinematographer, Ryuto Kondo, capture scenes from a seemingly straightforward eye, all the better to convince and deceive us with.

But then Monster shifts from Saori’s perspective to Mr. Hori’s, who’s regularly mocked by his hostess lover for his awkward smile and told by the school’s management that he’s “shifty-eyed and suspicious.” What happens to a person when they’re constantly told their appearance is off-putting? Replaying some of the earlier events and shedding light on others, we see that Minato’s accusations may not be true. There’s something more involved going on, and it includes Minato’s fellow student, Yori (Hinata Hiiragi), whose father (Shidō Nakamura) is an abusive drunk and calls Yori a “monster.” We also learn the origin of the “pig brain” insult and a song Minato sings with the refrain, “Who is the monster?” There’s a small collection of presumptions that the viewer makes based on what Kore-eda decides to show us, such as who may have set fire to the hostess bar, who killed a dead cat found near the school, or who was bullying whom. The director and his cinematographer, Ryuto Kondo, capture scenes from a seemingly straightforward eye, all the better to convince and deceive us with.

Employing a structure reminiscent of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), writer Yûji Sakamoto’s scenario unfolds patiently, reframing the perspective several times so that earlier scenes receive new contexts, challenging our initial impressions about what happened. But instead of assembling a puzzle into which all of the pieces gradually fall into place, Monster asks open-ended questions that more often lead to scenes of tenderness and tragedy. Sakamoto’s script—winner of the Best Screenplay award at this year’s Cannes Film Festival—doesn’t tie the drama into a bow to leave the viewer with a sense that order has been restored to the universe or absolute understanding has been achieved. Quite the opposite. It emphasizes that our perceptions about people are often wrong or, at the very least, far too simplistic. The late Ryuichi Sakamoto’s wounded score accents this tension, aurally evoking a thematic undercurrent beyond any single character.

Sakamoto’s script uses bold, figurative gestures of fire, water, and natural disasters to frame humanity’s intricacies. The film opens with the evocative sight of a building on fire, while its climactic scenes revolve around a typhoon and the resultant mudslide. Of course, characters also call each other “monster” at various times throughout the film to pointed effect. It’s an absolutist label, which seldom proves accurate as intended except for one case where there’s no excusing the character’s anti-gay hatred, and so there’s no other word for him. A thread in Sakamoto’s dialogue also involves reincarnation, with Saori talking to Minato about how his late father would be reborn. As a giraffe or a horse, perhaps? Minato also wonders how he would be reborn, and these thoughts of death in someone so young prove aching. Later, there’s a touch of the great beyond, which is familiar territory for the director—his 1998 film After Life remains one of the most imaginative conceptions of what awaits us. Though Kore-eda’s direction is subtle and nuanced, his bold, expressive imagery builds Monster into a thoughtful and moving allegory.

Writing in Aeon, Marina Benjamin describes a monster as “a figure of excess, difficult to absorb culturally.” Though she’s talking about the cultural critic Susan Sontag, repurposing the usually pejorative term in a positive light, Benjamin gets at something that emerges from Kore-eda’s film—the notion that labels cannot so easily summarize human beings. Monster is a deeply sensitive film about what we believe about people without ever getting to know them. We are all monsters in this sense, misjudging others despite a lack of context, and existing in a state of multidimensionality that defies simple categorization. By extension, Kore-eda and Sakamoto also reveal how film is a deceptive medium, only showing one perspective at a time—an assessment shared by the likes of Brian De Palma and Michael Haneke, who have both been quoted to the effect of “film is 24 lies per second.” Although Monster’s theme may ring cynical, it’s not without hope that some people may change, make the effort, and approach each other with compassion.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review