Saltburn

By Brian Eggert |

With just two credits as writer-director, Emerald Fennell has already established a few directorial signatures in her films. She tapped into the zeitgeist with her debut, Promising Young Woman (2020), for which she won the Oscar for Best Screenplay, but reduced its main character’s complexity, wounded psyche, and provocative rebellion with a simplistic conclusion that served the film’s discussion points rather than its dramatic integrity. But the film kept the viewer guessing through an array of unpredictable tonal shifts and serious themes, with a touch of shock treatment stylization at times. In the end, though, the feature almost destabilized any goodwill with an it-was-all-part-of-the-plan conclusion, which cheapened the nuance that came before. Her sophomore effort, Saltburn, suffers from an almost identical set of issues, even while, like its predecessor, the film is sharply written, terrifically acted, and decidedly engaging to watch. Unfortunately, Fennell resorts to silly games in her narrative structure in the end (I will discuss these aspects in detail below, so consider yourself warned), placing her characters’ many potential equivocations into a tidy box and robbing them of their potential to evoke much thought or lasting effect.

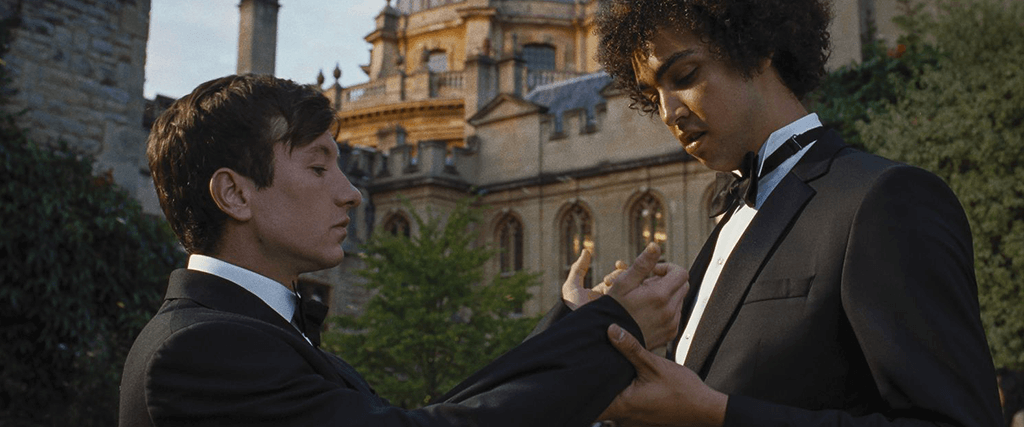

While Fennell targeted toxic masculinity, rape culture, and the absence of accountability with Promising Young Woman, she trains her cinematic arsenal at the casual cruelty, absurd excesses, and freakish idiosyncrasies of the exorbitantly rich in Saltburn. Her target proves so obvious that she hopes to relate to the mere 99% of her audience that doesn’t belong to the top 1%. The story is told from the perspective of Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan), who narrates from some time in the near future, when he seems to be giving testimony about a crime. Oliver is a seemingly naive freshman at Oxford who comes from a troubled background of drug-addicted parents. A wallflower, he doesn’t fit among his privileged fellow students, and he spends much of his time ogling the Adonis-like Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), hoping to become part of his insufferable clique. After weaseling his way into Felix’s graces, Oliver must contend with the superior abuses of Farleigh (Archie Madekwe), a Catton family relative whose America-based family relies on financial support from Felix’s parents, and so he jealously clings to his benefactor and remains suspicious of encroaching outsiders like Oliver.

At the end of the school year, the death of Oliver’s father prompts Felix to take pity and invite him to the Catton family estate, Saltburn, for the summer. There, Felix gives Oliver the grand tour, disinterestedly waving off some “hideous Rubenses” and a bed purportedly stained with Henry VIII’s semen. Only the flytrap spied in the chandelier suggests the rotten core of this lavish, venerable estate. Oliver soon becomes the subject of amusement for Felix’s nauseating, gaudy family, who supply a constant source of laughs from their sheer awfulness. His father is Sir James (Richard E. Grant), a veritable space case with deep pockets; his mother is Elsbeth (Rosamund Pike, terrific), a former model and acidic human being with a “deep and utter horror of ugliness.” Felix’s sister Venetia (Alison Oliver) makes herself available outside of Oliver’s bedroom window at night—even if she does think he’s a “surf,” she admits, “I think I like you even more than last year’s one.” To be sure, the Cattons keep people around to amuse them. Take Pamela (Carey Mulligan), who overstays her welcome with her tattoos, tacky style, and dour mood that no longer entertains Elspeth, so she’s quietly ushered out one morning by their equally elitist butler, Duncan (Paul Rhys, excellent).

Fennell works with cinematographer Linus Sandgren, who applies a palette of fleshy, saturated colors to convey the hedonism on display. This is a gorgeous-looking film, with intimate compositions, bold uses of color, and images no viewer will soon forget. Yet, it’s all very similar to his work on last year’s Babylon. But unlike that expansive film, Saltburn feels like a secret world at which we’re peering through the keyhole. It’s a theme reflected in Fennell’s use of the boxy Academy aspect ratio—the overused choice of arthouse filmmakers to convey claustrophobic or isolated worlds—to mirror how Oliver often looks through open doorways to spy Felix having sex or masturbating. Oliver weaponizes sexuality in the film, but his infatuation remains with Felix. It’s difficult to decide which scene is more brazenly debauched: the sequence when Oliver sips leftover bathwater out of Felix’s tub or the long shot where Oliver, after a funeral, screws a fresh grave. Moments such as these, and many others in the film, will incite vocal reactions of laughter and revulsion from audiences, making Saltburn one of the more participatory viewing experiences in recent memory.

Fennell works with cinematographer Linus Sandgren, who applies a palette of fleshy, saturated colors to convey the hedonism on display. This is a gorgeous-looking film, with intimate compositions, bold uses of color, and images no viewer will soon forget. Yet, it’s all very similar to his work on last year’s Babylon. But unlike that expansive film, Saltburn feels like a secret world at which we’re peering through the keyhole. It’s a theme reflected in Fennell’s use of the boxy Academy aspect ratio—the overused choice of arthouse filmmakers to convey claustrophobic or isolated worlds—to mirror how Oliver often looks through open doorways to spy Felix having sex or masturbating. Oliver weaponizes sexuality in the film, but his infatuation remains with Felix. It’s difficult to decide which scene is more brazenly debauched: the sequence when Oliver sips leftover bathwater out of Felix’s tub or the long shot where Oliver, after a funeral, screws a fresh grave. Moments such as these, and many others in the film, will incite vocal reactions of laughter and revulsion from audiences, making Saltburn one of the more participatory viewing experiences in recent memory.

Similar to Promising Young Woman, I found myself thoroughly immersed in Saltburn initially, for the first two hours of the 131-minute runtime, until the finale, which soured much of my goodwill toward what preceded it. In the end, Fennell and her editor, Victoria Boydell, resort to a twist reminiscent of the Keyser Söze reveal in The Usual Suspects (1995)—a montage that accumulates how Oliver has willfully maneuvered his way into the Cattons’ favor. When finally rejected, he exploits and murders them to acquire their wealth. Except, Fennell doesn’t leave obvious clues for the viewer to discover throughout Saltburn, building to a natural revelation that we missed. Rather, this cheap and gimmicky conclusion has a non-sequitur quality that invents scenes never shown to us. It’s not a case of the filmmaker cleverly hiding details in plain sight; it’s a matter of Fennell changing the nature of her story at the last minute, to a somewhat incongruous effect. For instance, when the full circumstances of the flash-forwards to Oliver recounting his experiences at Saltburn for an interrogation or confession are shown, they raise questions about why he’s recounting the story at all—except for the moviegoer’s benefit, that is.

Certainly, one could argue that it’s not about the destination; it’s about the journey. But Fennell’s twist in the final act changes the dynamic between Oliver and the Cattons from something resembling Cruel Intentions (1999), where the super-rich mock and manipulate an apparent innocent from a lower class, to something more schemy and less challenging. Fennell turns Oliver into a dumbed-down, more intentional version of Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley—albeit without the empathy and human entanglement Anthony Minghella supplied the character in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999). If Oliver is tantamount to Matt Damon’s Tom, then Felix is Jude Law’s object of affection as Dickie Greenleaf, Farleigh is the equivalent of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s pretentious jerk intent on exposing Tom and preserving Dickie for himself, and Velentia supplies the initially sympathetic but eventually suspicious Gwyneth Paltrow role. Unlike Minghella’s film, Fennell disseminates information about her characters with all the subtlety of a leather sap to the head.

Perhaps we should have guessed it. After all, if there’s one thing we can be sure of watching Saltburn, families who invite Keoghan into their homes risk destroying themselves from within. His character’s arc recalls his similar role in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), which dealt with many identical themes of punishing the apathy, irresponsibility, and warped dynamics of powerful people. Instead of eating spaghetti with morbid intensity, however, he goes down on Venetia during her period with vampiric delight. A slippery, fascinatingly unstable presence (he’s compared to a spider in some overwrought imagery), Keoghan demonstrates that he’s one of today’s most hypnotically watchable actors, and here, he takes plenty of risks in bold, daring scenes of extreme debauchery. Those shocking elements keep the viewer watching, with Fennell inventing several moments that viewers might mistake for originality. Even though Saltburn pushes the limits of what we’ve seen depicted onscreen, the story has plenty of superior, more beguiling antecedents.

Perhaps we should have guessed it. After all, if there’s one thing we can be sure of watching Saltburn, families who invite Keoghan into their homes risk destroying themselves from within. His character’s arc recalls his similar role in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), which dealt with many identical themes of punishing the apathy, irresponsibility, and warped dynamics of powerful people. Instead of eating spaghetti with morbid intensity, however, he goes down on Venetia during her period with vampiric delight. A slippery, fascinatingly unstable presence (he’s compared to a spider in some overwrought imagery), Keoghan demonstrates that he’s one of today’s most hypnotically watchable actors, and here, he takes plenty of risks in bold, daring scenes of extreme debauchery. Those shocking elements keep the viewer watching, with Fennell inventing several moments that viewers might mistake for originality. Even though Saltburn pushes the limits of what we’ve seen depicted onscreen, the story has plenty of superior, more beguiling antecedents.

Among Fennell’s many visual and narrative sources is Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975). But where Kubrick’s painterly visuals and characteristic emotional distance challenge the viewer to empathize as that film’s lower-class opportunist schemes his way to the top, Fennell’s approach doesn’t have that much faith in the audience. While the specifics may be novel and entertainingly base, Saltburn’s familiar plotting and unsubtle desire to be clever amounts to a hackneyed resolution that ultimately makes Oliver less interesting and multifaceted. The writer-director’s desire to take down the idle rich is so strong that it overwhelms the material’s potential ambiguity, and Oliver is little more than a tool in that agenda. Then again, the facile message might be easier to swallow if Fennell’s methods in the finale weren’t so rooted in clunky trickery. And while this is blunt-force storytelling, it’s easy to see why so many have shouted their praises for Saltburn. Fennell is unquestionably a skilled filmmaker, and her second feature deserves to be seen, but neither her narrative methods nor the film’s substance add up to much.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review