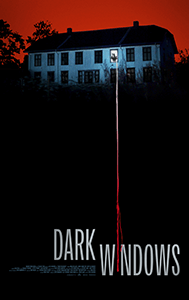

Dark Windows

By Brian Eggert |

Dark Windows has a setup that recalls many body-count movies, but then, just when it seems like the movie will supply the basic pleasures of the horror genre, it meanders into the melodrama of an after-school special. It’s about four teens who engaged in reckless horseplay while driving, which led to a car accident. Their friend Ali (Grace Binford Sheene) didn’t make it, and the three survivors kept the truth about what happened that night a secret. In the aftermath, they decide to grapple with their trauma at a secluded summer house. While there, a masked killer seeks revenge, prompting a home invasion scenario. But before the movie plunges into its torture-laden climax, the filmmakers drag out the proceedings with tedious, manufactured conflicts and awkward dramatics that stretch the 80-minute feature to an unbearable length.

The movie opens with the promise that something exciting will eventually happen. Tilly (Anna Bullard) is surrounded by photos of Ali in the summer house at night. We see a knife and some pills scattered on the floor, and we hear the sound of someone trying to break in. Armed with a baseball bat, Tilly calls for help. Then the intruder enters the room, and Tilly meets him with a look of recognition. Here, the filmmakers implant a whodunit element, raising questions about who would want to harm Tilly and why. Cut to a few days earlier, and Tilly attends the wake of her dead friend, Ali. Tilly was behind the wheel, we are told, and her guilt consumes her. Reeling from grief and remorse, Tilly agrees to a getaway with her besties, the mean girl Monica (Annie Hamilton) who declares “It’s time to move on” a couple of days after her friend is buried, and the jokester Peter (Rory Alexander) who drinks too much.

Doubtless, the killer is among those who attended the wake. Could it be Ali’s boyfriend Andrew (Thomas Takyi) who refuses to talk to Tilly? Or maybe it’s Ali’s creepy Uncle Bob (Morten Holst)? We forget these questions during the protracted second act, which finds the three survivors consumed by interpersonal drama. At the summer house, Monica carries on a text conversation with Ali’s boyfriend. Peter swigs from his flask and continues to drink too much, so Tilly reminds him that his father died from alcoholism. When confronted, Peter reacts with moody petulance. Between its heavy-handed treatment of the car accident and alcoholism, Dark Windows has the makings of a Lifetime Original. And since nothing interesting is happening between the teens, the three credited editors pass the time by cutting to idyllic pastoral shots of a butterfly, a bumblebee, and sunlight passing through the trees. By this time, boredom sets in.

Meanwhile, there’s plenty about Dark Windows that seems generic or just plain off, perhaps because it’s a European production trying to pass as an American low-budget indie. The dialogue sounds like it was written by someone whose grasp of English was tenuous, with characters who speak unnatural lines and banalities. All the characters seem to believe the events take place in America, but any attentive viewer will see they do not. Some of the details look right. For instance, at one point, a character pays in US dollars at a general store. But when there’s an emergency, and Tilly dials 9-1-1, the ringtone doesn’t sound right. The director and writer hail from Norway, as do some of the actors, and the surroundings were clearly captured in Norway. That might explain why Ali’s father (Jóel Sæmundsson) and Uncle Bob have slight accents.

Meanwhile, there’s plenty about Dark Windows that seems generic or just plain off, perhaps because it’s a European production trying to pass as an American low-budget indie. The dialogue sounds like it was written by someone whose grasp of English was tenuous, with characters who speak unnatural lines and banalities. All the characters seem to believe the events take place in America, but any attentive viewer will see they do not. Some of the details look right. For instance, at one point, a character pays in US dollars at a general store. But when there’s an emergency, and Tilly dials 9-1-1, the ringtone doesn’t sound right. The director and writer hail from Norway, as do some of the actors, and the surroundings were clearly captured in Norway. That might explain why Ali’s father (Jóel Sæmundsson) and Uncle Bob have slight accents.

The press materials describe the plot of Dark Windows as being about “a masked man with sinister motives who terrorizes a group of teenagers on their weekend getaway at a cabin in the woods.” Much of that is inaccurate. None of these actors look like teenagers; they’re each either in or nearing their thirties. Most of the events take place at a lofty European-style country house, which would look more appropriate in an Ingmar Bergman movie than a teen slasher. It’s about ten times the size of the cabin in, say, The Evil Dead (1981) or The Cabin in the Woods (2012). And while there’s a forest nearby, the estate is situated on a plot of open country. However, there is a masked man with sinister motives. He shows up in the background in several shots, spooking the viewer. But it’s not clear that he’s wearing a mask until much later in the movie–he’s only shown in silhouette or as an out-of-focus figure until later. Cinematographer Jens Ramborg also adopts a POV shot à la Halloween (1978) to show the killer watching his prey from the bushes.

The director is Alex Herron, who made Leave last year. Ulvrik Kraft, credited as Wolf Kraft, wrote the screenplay. Their attempt at an American horror movie is artificial and uneasy, and their forced treatment of their characters plays out in tedious scenes of unconvincing drama that become unintentionally funny. The only less compelling aspects are the friends’ secret and the killer’s identity. Doubtless, the filmmakers wanted to break into the US’s lucrative low-budget horror market by repurposing elements from successful movies. The score by Kim Berg, for example, consists of booms, winding metal, and jittery ratcheting that sound sampled from countless movies like this one. However, none of these imitative flourishes work. What might be interesting is if Herron made a Norwegian horror film specific to his country and culture, but with this lame imitation, he’s not convincing anyone.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review