Passages

By Brian Eggert |

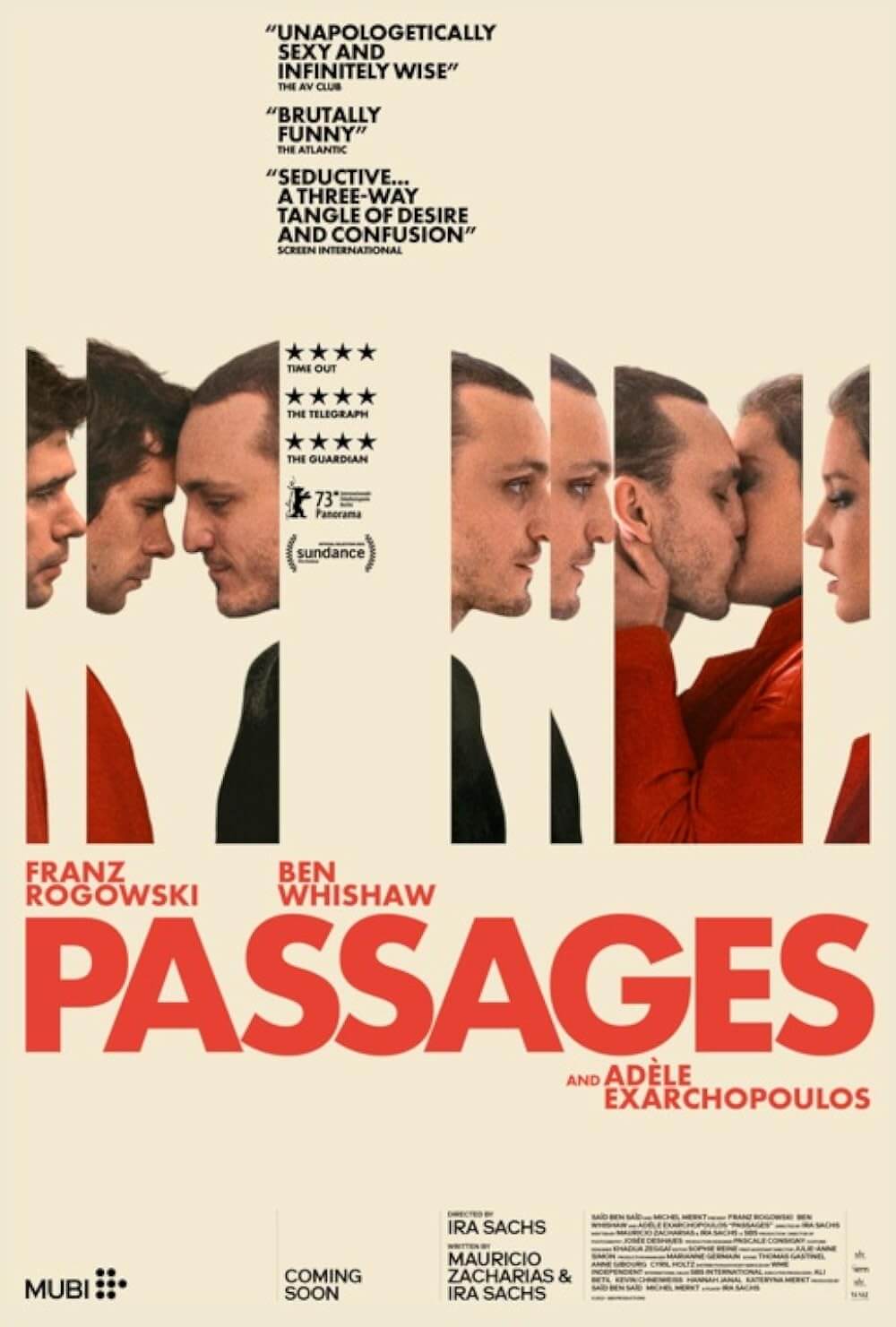

Ira Sach’s Passages opens on a film set, a period piece whose costumes look tacky and whose action seems forced. The production’s impatient director, Tomas (Franz Rogowski), struggles to articulate what he wants. He corrects how an extra is holding her drink, and then he gives repeated, vague instructions to an actor about descending some stairs before finally losing his temper and acting out the scene himself. You get the sense that Tomas sees himself as a genius and that all orbits around his gravity. Worse, through the course of Sach’s film, Tomas is revealed to be selfish, insecure, and predatory. Whether he changes at all is debatable. Passages finds Tomas at the center of a tragic and open-hearted love triangle, whose other members finally realize the extent of Tomas’ narcissism, but not before sacrificing time and emotional energy on him. Ever the sophisticated examiner of his characters’ many textures, Sachs considers a profoundly awful person without alienating his audience, resulting in a kind of magic trick. Fortunately, Rogowski’s incredible performance makes the character a fascinating subject to observe.

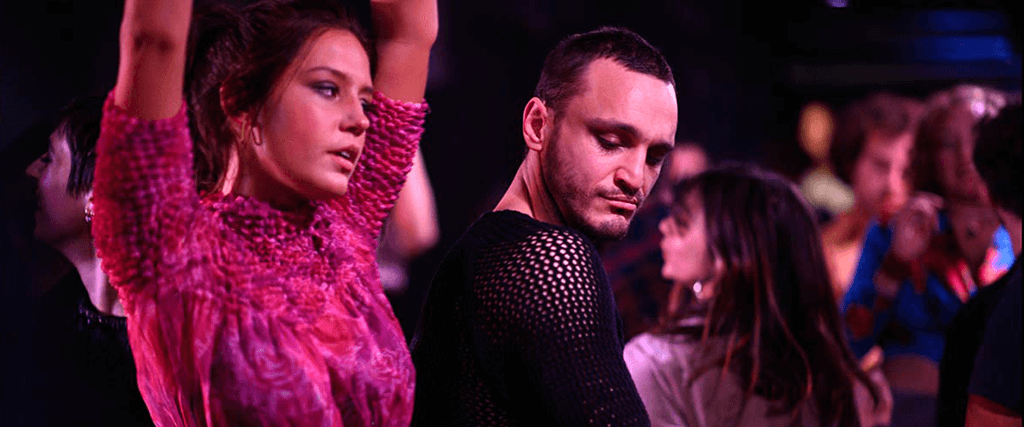

Passages is a thorny film because its unpleasant central character might upset some in the audience who recognize the protagonist’s pattern of behavior. Before the full spectrum of his self-absorption becomes evident, however, it’s not difficult to see his appeal. At a wrap party, Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos) breaks up with her boyfriend only to find herself dancing with Tomas, whose husband, the graphic designer Martin (Ben Whishaw), has left the party. They lose themselves, rapt by their connection to the thumping electronic music. Later, they sleep together and find themselves once again in sync. When Tomas returns home late the following day, he tells Martin, “I had sex with a woman.” Although Martin is visibly upset by this news, Tomas goes on sharing, with the expectation that Martin should be happy about his husband’s new experience. “I felt something that I haven’t felt in a very long time,” Tomas says. “It was exciting. It was different.” He doesn’t seem to understand why Martin wouldn’t be interested. Instead, Martin is in a rush to leave for a class, rationalizing, “It’s fine,” though it is clearly not. “This always happens when you finish a film.”

What seems initially like an affair turns into a full-fledged love triangle when Tomas starts referring to Martin as a “brother,” confesses his love for Agathe, and confronts Martin with the question: “Can you really say that you love me?” Tomas implants whatever justification he needs to end things with Martin and move in with Agathe, because that’s what he wants at the moment. But his possessiveness over Martin doesn’t subside, especially when, after their separation, Martin begins seeing a writer, Ahmad (Erwan Kepoa Falé). At this, Tomas returns to their former apartment unannounced, grows temperamental with Agathe, and shows internal panic over his jealousy. Tomas might justify his behavior as a feeling person since no matter what he feels, he embraces the impulse because it is genuine, regardless of what damage he causes. This leads to unbearable moments where the triangle attempts to share a country house, and Tomas finds his way into Martin’s bedroom, with Agathe listening to their sounds through the walls. But Tomas’ egoism and thoughtlessness culminate in a lunch with Agathe’s parents (Caroline Chaniolleau, Olivier Rabourdin), who size Tomas up in a few minutes.

It’s impossible to look at Passages and not wonder whether Sachs has drawn inspiration from his life and to question whether the filmmaker sees himself in Tomas. Sachs and his partner, painter Boris Torres, have two children with documentarian Kirsten Johnson (Dick Johnson is Dead, 2020), who lives near them in Manhattan and shares parenting responsibilities along with her wife Tabitha Jackson, director of the Sundance Film Festival. Is Tomas what might’ve occurred had Sachs inhabited Bizarro World, where he remained indecisive about his feelings, walked away from conversations he didn’t want to have, and pursued every desire without thinking it through and considering the consequences? Regardless of how horribly Tomas may behave, perhaps Passages is Sachs’ work of earnest gratitude that his situation among three mature adults didn’t play out differently. But even in Tomas’ speculative specificity, he’s a universal character in that surely you’ve met someone as toxic as Tomas, be it a former lover or someone you now avoid after learning the hard way what they’re capable of.

It’s impossible to look at Passages and not wonder whether Sachs has drawn inspiration from his life and to question whether the filmmaker sees himself in Tomas. Sachs and his partner, painter Boris Torres, have two children with documentarian Kirsten Johnson (Dick Johnson is Dead, 2020), who lives near them in Manhattan and shares parenting responsibilities along with her wife Tabitha Jackson, director of the Sundance Film Festival. Is Tomas what might’ve occurred had Sachs inhabited Bizarro World, where he remained indecisive about his feelings, walked away from conversations he didn’t want to have, and pursued every desire without thinking it through and considering the consequences? Regardless of how horribly Tomas may behave, perhaps Passages is Sachs’ work of earnest gratitude that his situation among three mature adults didn’t play out differently. But even in Tomas’ speculative specificity, he’s a universal character in that surely you’ve met someone as toxic as Tomas, be it a former lover or someone you now avoid after learning the hard way what they’re capable of.

Penned with Sachs’ longtime co-writer Mauricio Zacharias, who has been collaborating with the director for a quarter-century since his debut film, The Delta (1997), the screenplay is intelligent and precise. Sophie Reine’s editing further reduces Passages to an impressive economy of scenes. Not a moment of the 91-minute runtime feels wasted, with the deceptively simple camerawork by cinematographer Josée Deshaies (Saint Laurent, 2014) suggesting Tomas’ self-obsession by gravitating toward him and cutting others out. Shot with muted, soft, and natural colors, the film looks about as close to a European arthouse film as an American production could get, complete with the decidedly un-commercial rating. Rather than accept the NC-17 that MPA initially stamped on the film—for an ultimately tame sex scene between Tomas and Martin, exposing only the MPA’s heteronormative biases when issuing their decrees—Sachs resolved for an “unrated” label. Even so, Passages was picked up by Mubi after its debut at Sundance and will find a small but engaged audience, as most of Sachs’ films do.

Sachs and Zacharias never resort to melodramatic speeches or forced dramaturgy, though perhaps that’s thanks to the actors. Rogowski, the German performer whose presence elevated Christian Petzold’s Transit (2019) and Undine (2021), plays Tomas as a force that bounces between whoever gives him the most attention, yet the actor’s presence pulls the viewer inward instead of repelling us. Whishaw gives the most sensitive and genuine turn, hurting the most openly as Martin. But Exarchopoulos imbues Agathe with an inner strength that survives Tomas’ worse betrayal with aching consequences, offering the most complex character. When he comes crawling back, she delivers a searing line that might sound like a cliché by another performer: “Look at you. It’s like you’re not the same person. Your face is ugly now.” In the end, when Tomas rides his bike with a hint of desperation, racing down the street to a jazzy marching band version of “La Marseillaise” on the film’s soundtrack, unable to bounce back and forth between Martin and Agathe any longer, he almost manages to earn some empathy. Maybe this is the lesson he needed to change. Then again, perhaps he will never change.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review