Reader's Choice

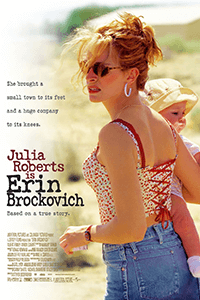

Erin Brockovich

By Brian Eggert |

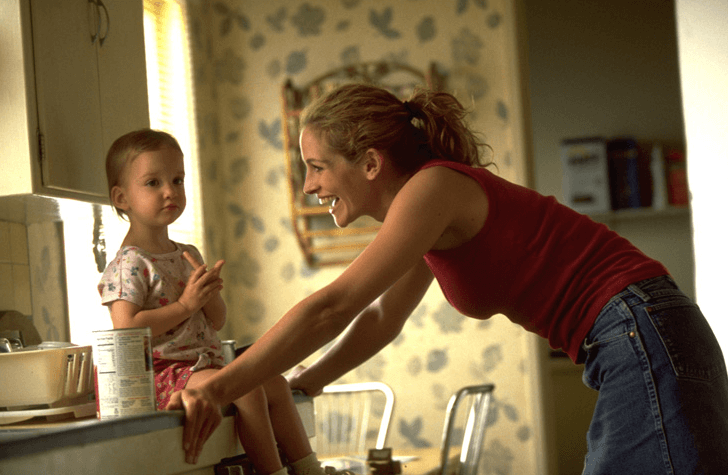

With Erin Brockovich, Steven Soderbergh wields Julia Roberts’ star power to draw public attention to an environmental issue. It’s a shrewd tactic, but typical of the director using A-list actors to expose predatory corporate and capitalistic behaviors. In a modest but inspiring David and Goliath story, Soderbergh’s film follows a single mother of three who talks her way into a minimum-wage job answering phones at an attorney’s office. Before long, she finds herself spearheading a case against a California utility, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), resulting in the biggest direct-action lawsuit settlement ever at that time. “If you’re trying to sneak something under the wire,” Soderbergh told an interviewer, “By which I mean an adult, intelligent film with no sequel potential, no merchandising, no high concept, and no big hook, it’s nice to have one of the world’s most bankable stars sneaking under with you.” Of course, at the turn of the century, few names were associated with the term “Movie Star” as fully as Julia Roberts, then America’s Sweetheart, known for playing women of a certain warmth, genuineness, and moral standing. Even while playing the titular character, distinct for her foul language, animal print garb, and considerable cleavage, Roberts exudes a moral integrity that, combined with some of Erin’s eyebrow-raising behavior, makes her so compelling.

The role harkened back to Robert’s star-making part in Pretty Woman (1990), where she plays a sex worker who defies the usual movie characteristics for such a role, offering a wholesome and empathetic girl-next-door quality instead. Roberts’ presence encourages audiences to look beyond her Pretty Woman character’s tacky outfits and the predominantly offscreen realities of her métier. She brings a similar effect to Soderbergh’s film, reframing the legal drama from an unprofessional woman’s perspective. Comparable films often center on an attorney, usually a man, whose career objectives are refocused by a case that activates his moral outrage. A Civil Action, released a year before Erin Brockovich, features John Travolta as a beleaguered, small-time lawyer who fights a legal battle against the high-paid corporate attorneys in a groundwater contamination case. Similarly, Dark Waters (2019) features Mark Ruffalo as a corporate defender who risks his prestigious pharmaceutical law career to flip sides against DuPont over the dumping of PFOAs. Next to these conventional examples, Soderbergh’s film offers fewer courtroom scenes or legal jargon. The story unfolds from Erin’s everyday position—that of an average woman who recognizes wrongdoing when she sees it and has genuine empathy for the plaintiffs, which she uses to convince them to join the class-action suit.

Screenwriter Susannah Grant revisits this theme in her by-the-numbers script. Everyone in official positions underestimates Erin’s intelligence, but she proves them wrong with her attention to detail, investigative skills, and ability to connect with common people. In scene after scene, someone judges Erin by her stereotypically indecorous appearance and sharp mannerisms, only to have her prove their superficial assessments wrong. One victorious scene finds her delivering a lynchpin document to an attorney (Peter Coyote), who looks on befuddled. “How’d you do this?” he asks. Erin replies with her typically sarcastic tone: “Seeing how I have no brains or law expertise […] I just went out there and performed sexual favors. Six hundred and thirty-four blow jobs in five days. I’m really quite tired.” Moments like this prove frequent and satisfying, giving way to a crowd-pleasing high. Not only does Erin Brockovich tell an underdog story about citizens from the small Southern California town of Hinkley taking on the callous PG&E, but it also tells a story about a woman rising in a man’s world, following third-wave feminist precepts by employing her smarts and sexuality to her advantage—evidenced in a famous scene where she weaponizes her low-cut top to convince a distracted clerk to give her unfettered access to public records.

Screenwriter Susannah Grant revisits this theme in her by-the-numbers script. Everyone in official positions underestimates Erin’s intelligence, but she proves them wrong with her attention to detail, investigative skills, and ability to connect with common people. In scene after scene, someone judges Erin by her stereotypically indecorous appearance and sharp mannerisms, only to have her prove their superficial assessments wrong. One victorious scene finds her delivering a lynchpin document to an attorney (Peter Coyote), who looks on befuddled. “How’d you do this?” he asks. Erin replies with her typically sarcastic tone: “Seeing how I have no brains or law expertise […] I just went out there and performed sexual favors. Six hundred and thirty-four blow jobs in five days. I’m really quite tired.” Moments like this prove frequent and satisfying, giving way to a crowd-pleasing high. Not only does Erin Brockovich tell an underdog story about citizens from the small Southern California town of Hinkley taking on the callous PG&E, but it also tells a story about a woman rising in a man’s world, following third-wave feminist precepts by employing her smarts and sexuality to her advantage—evidenced in a famous scene where she weaponizes her low-cut top to convince a distracted clerk to give her unfettered access to public records.

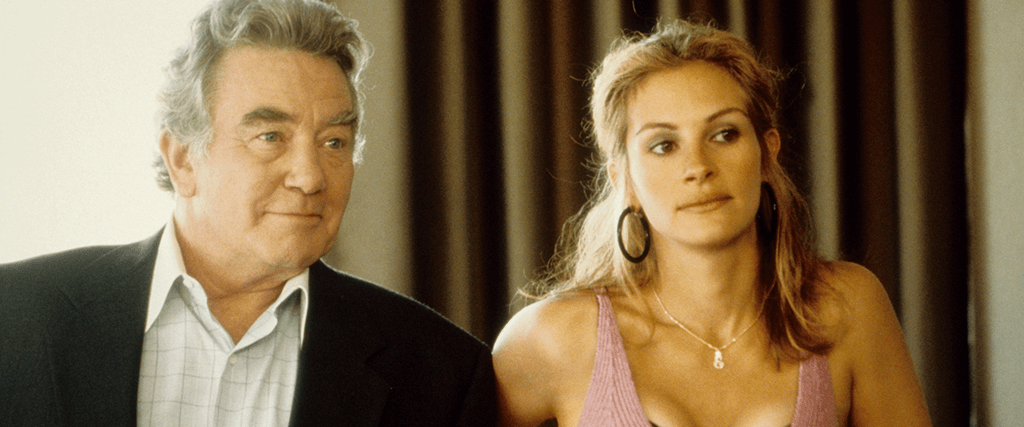

However punchy and sexualized Roberts’ role might be, the scenes that work best in Erin Brockovich involve Erin’s humorous, combative bond with her employer and quiet scenes of human connection with the plaintiffs. Albert Finney plays Edward L. Masry, the self-made attorney with a small practice in Los Angeles. In Hinkley, PG&E attempted to buy victims out of their homes who were exposed to a dangerous carcinogen in the water, Chromium 6, but not before claiming the chemical compound was safe. Finney fits nicely into his role as a stuffy but good-hearted lawyer who gives Erin a chance after botching her sure-thing car accident suit in the opening scenes. Although capable and fatherly, he relies on Erin’s rapport with people and ability to keep the PG&E case details organized; he even needs her to tie his necktie before a meeting, suggesting she’s the fierce office den mother. Keeping a professional exterior, Ed cannot help but admire Erin, leading to satisfying moments when he breaks his self-serious demeanor for a moment of sincerity and humor he has been so reticent to show.

Grant’s script comes alive thanks to the performances, particularly Roberts’ and Finney’s. Roberts showboats in a role that both plays to her strengths and offers a more imposing version of her usual persona. For instance, Erin quickly lashes out at coworkers (like the one played by Conchata Ferrell), announcing in one volatile scene, “I’m not talking to you, bitch!” She might be accused of creating a toxic workplace today. Even so, tender moments where Erin bonds with a victim of the contamination (Marg Helgenberger) remain affecting, and Roberts displays convincing compassion. Elsewhere, Erin’s relationship with George (Aaron Eckhart), her neighbor and eventual romantic partner, a rugged biker who’s willing to drop everything to babysit her kids every day, feels underserviced. An affable performance from Eckhart counteracts his character’s vague backstory. Similar to Finney’s role, there’s not much for Eckhart to do, except lend his screen presence to boost the main character—an apt gender role reversal, given that in legal dramas, the male lawyer’s love interest is usually underdeveloped.

Compared to Soderbergh’s previous two features, Out of Sight (1998) and The Limey (1999), which capitalized on Hollywood’s then-current post-Tarantino love affair with nonchronological stories either inspired by or written by Elmore Leonard, Erin Brockovich was a change of pace for the director. Whereas the two earlier films deployed an out-of-order structure and saturated the viewer in slick capers, Soderbergh’s first twenty-first-century production was an “aggressively linear reality-based drama” in his mind. The film might also be the least stylized of his career. In a rare example of the director not serving as his own cinematographer under the pseudonym Peter Andrews, Soderbergh teams with d.p. Ed Lachman, who shot The Limey. There’s a recessive, straightforward aesthetic at work in the filmmaking, even more than some might perceive as Soderbergh’s usual approach. A few color saturations (yellow for the barren landscape around Hinkley, blue and green for nighttime scenes) anticipate his more fully committed use of this tactic on Traffic, while the minor presence of jump cuts courtesy of editing legend Anne V. Coates hint at Soderbergh’s affinity for New Wave techniques.

Compared to Soderbergh’s previous two features, Out of Sight (1998) and The Limey (1999), which capitalized on Hollywood’s then-current post-Tarantino love affair with nonchronological stories either inspired by or written by Elmore Leonard, Erin Brockovich was a change of pace for the director. Whereas the two earlier films deployed an out-of-order structure and saturated the viewer in slick capers, Soderbergh’s first twenty-first-century production was an “aggressively linear reality-based drama” in his mind. The film might also be the least stylized of his career. In a rare example of the director not serving as his own cinematographer under the pseudonym Peter Andrews, Soderbergh teams with d.p. Ed Lachman, who shot The Limey. There’s a recessive, straightforward aesthetic at work in the filmmaking, even more than some might perceive as Soderbergh’s usual approach. A few color saturations (yellow for the barren landscape around Hinkley, blue and green for nighttime scenes) anticipate his more fully committed use of this tactic on Traffic, while the minor presence of jump cuts courtesy of editing legend Anne V. Coates hint at Soderbergh’s affinity for New Wave techniques.

Erin Brockovich was released in March 2000, more than half a year before the usual awards baiting begins. But critics and awards groups didn’t forget about the film, perhaps because Soderbergh’s Traffic, released in late December of that year, reminded them of the director’s one-two punch. Between the two features, Soderbergh earned dozens of awards and nominations, including five Oscar nominations for each film. Traffic won four statues out of its five categories, including Best Director; Erin Brockovich’s sole Oscar went to Roberts for Best Actress, with voters reminded of her performance given the film’s recent arrival on DVD, the new-ish home video format that had reinvigorated the ancillary marketplace. Beyond the overwhelmingly positive response from critics and audiences, Erin Brockovich marked a breakthrough for Roberts, who took home $20 million of the production’s $52 million budget. While the performers in Traffic took salary cuts to contribute to the ensemble, Roberts became the first woman in Hollywood to command a salary on the scale of Harrison Ford or Tom Cruise.

Erin Brockovich remains a Julia Roberts vehicle, perhaps even designed in some respect to earn her an Oscar. Conventional as it may seem, Soderbergh delivers a refreshing anti-court legal drama. Whereas other examples in the genre resolve their conflicts in big, emotional courtroom scenes, Soderbergh and Grant follow their non-lawyer character to humanize the conflict from the perspective of a woman who not only isn’t an attorney but doesn’t conform to the legal milieu. Additionally, Soderbergh’s mistrust of corporate greed and government oversight—seen in his Traffic, Ocean’s Eleven (2001), The Good German (2006), The Informant! (2009), Contagion (2011), Side Effects (2013), Unsane (2018), The Laundromat (2019), No Sudden Move (2021), and KIMI (2022)—results in a film that feels straightforward enough but has a sneaky edge in its protagonist. Rather than offering a subversive style or narrative conceit, Soderbergh allows Roberts to take center stage as an ordinary person challenging the system. Selflessly directed, Erin Brockovich is a sly film that banks on Roberts’ power to draw audiences in, and then convey a warranted critique of utilities that don’t have their community’s best interests in mind. However un-Soderbergh-like the film looks, it conforms with his long-held interest in questioning broken and corrupt systems.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on July 27, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review