Evil Dead Rise

By Brian Eggert |

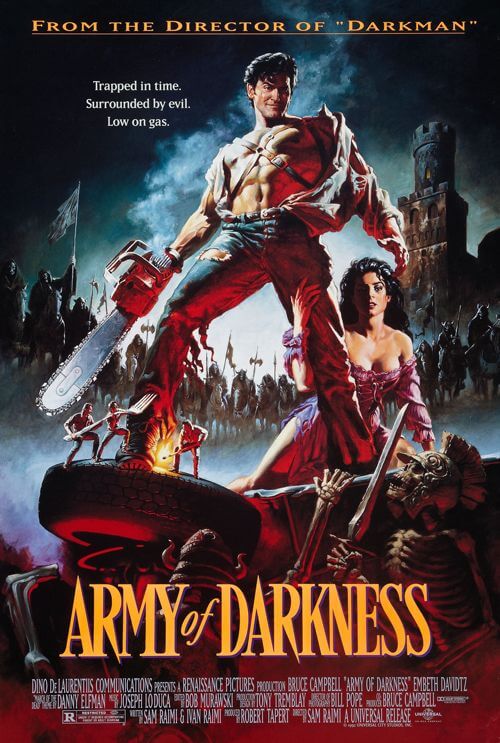

Evil Dead Rise is a movie made by someone who grew up watching Evil Dead movies and not the Three Stooges. That distinction matters. Sam Raimi, director of the original three movies in the franchise—The Evil Dead (1981), Evil Dead 2 (1987), and Army of Darkness (1992)—used his love of slapstick to heighten the horror and conjure larger-than-life physical performances from star Bruce Campbell, among the most celebrated in the genre’s history. Irish filmmaker Lee Cronin, the writer-director of Evil Dead Rise, makes the same mistake as Fede Álvarez did with his 2013 reboot-spinoff-thing by concentrating on gore and having little sense of humor about itself. Cronin delivers some memorably stomach-churning sights, including an eyeball sucked out of a victim’s head, a cheese-grated leg, and a wood chipper sequence. But in his clumsy attempts to pay homage to Raimi’s movies, complete with lines of dialogue borrowed from the originals, Cronin makes Evil Dead Rise into an ample gorefest while underselling the cartoonish glee of Raimi’s aesthetic that defines this franchise.

The problem with remaking The Evil Dead is that the film’s most important quality is stylistic, and few filmmakers can do Raimi well. Raimi’s pervasive wide-angle lenses, fluid camerawork, rampant POV shots, and physical comedy enrich the proceedings, while the storylines in the three films are little more than a primer. Peter Jackson made a worthy imitation with Dead Alive (aka Braindead, 1992), one of the goriest romantic comedies ever made. But not many others have effectively parroted his maneuvers, nor should they want to—he is a true original, and copying him would only underscore their absence of creativity. Aside from a few visual homages, Cronin, in his sophomore effort after 2019’s A Hole in the Ground, attempts to replicate the aesthetic but achieves only Sam Raimi Lite, offering recognizable flourishes but with the edge dulled. Evil Dead Rise would have been better served by Cronin setting aside all Raimi-isms and starting afresh.

At least Cronin’s screenplay distinguishes itself from the earlier movies. After a familiar cabin-in-the-woods prologue, the story resets to a dilapidated apartment complex in Los Angeles, a former bank slated for destruction in a month. After learning she’s pregnant, Beth (Lily Sullivan), a guitar technician who travels with a band and doesn’t want to be called a roadie, worries about becoming a mother. She arrives at the building to visit her sister, Ellie (Alyssa Sutherland), a tattooist mother grappling with her husband’s abandonment and trying to manage three children—the rebellious activist, Bridget (Gabrielle Echols); the wannabe DJ, Danny (Morgan Davies); and the rambunctious youngster, Kassie (Nell Fisher). When the kids return from getting pizza on this dark and stormy night, an earthquake strikes, revealing a long-enclosed section of the former bank. Danny explores, only to find an exposed vault decked out in crucifixes. Danny snatches a book and three vintage vinyl records from 1923 before the kids head back to the apartment, where, inevitably, he plays passages from the ancient Book of the Dead read aloud by a curious priest.

There’s no mention of “Deadites” or “Kandarian demons,” but Danny unleashes a recognizable breed of demonic force that races toward the apartment building in a furious drone shot. At the same time, the book, made from human flesh and inked in blood, flips through its pages to choose how it will torment its first victim. The book stops on a depiction of a possessed woman, and it has chosen Ellie. The book makes a similar choice for each new victim, defining the abject monster born at that moment. Sutherland’s sharp facial features and chilling smile (worthy of last year’s Smile) make her fiendish presence particularly arch, especially when Ellie attacks and taunts her family. Indeed, the idea of a mother trying to mutilate and possess her children, whom she calls “titty-sucking parasites,” is disturbing. And while Cronin adds to the body count with victims from neighboring apartments, the nightmarish notion of the family turning on itself keeps the viewer invested. In her last moment of clarity, Ellie tells Beth, “Don’t let it take my babies.” For all of her efforts, Beth isn’t entirely successful, and it’s a bold choice on Cronin’s part to involve children in such wildly horrific situations.

There’s no mention of “Deadites” or “Kandarian demons,” but Danny unleashes a recognizable breed of demonic force that races toward the apartment building in a furious drone shot. At the same time, the book, made from human flesh and inked in blood, flips through its pages to choose how it will torment its first victim. The book stops on a depiction of a possessed woman, and it has chosen Ellie. The book makes a similar choice for each new victim, defining the abject monster born at that moment. Sutherland’s sharp facial features and chilling smile (worthy of last year’s Smile) make her fiendish presence particularly arch, especially when Ellie attacks and taunts her family. Indeed, the idea of a mother trying to mutilate and possess her children, whom she calls “titty-sucking parasites,” is disturbing. And while Cronin adds to the body count with victims from neighboring apartments, the nightmarish notion of the family turning on itself keeps the viewer invested. In her last moment of clarity, Ellie tells Beth, “Don’t let it take my babies.” For all of her efforts, Beth isn’t entirely successful, and it’s a bold choice on Cronin’s part to involve children in such wildly horrific situations.

Much of Evil Dead Rise occurs in the family’s apartment, though the spatial geography isn’t entirely clear. Still, production designer Nick Bassett creates convincing dank, drab spaces for the ensuing mayhem, lending the movie a grimy, hopeless quality. Once the power goes out in the building, Cronin and cinematographer Dave Garbett resort to shadowy scenes and jarring figures emerging in the background. There’s also a nifty sequence shot from a peephole, looking into the dark hallway as Ellie disposes of the neighbors. However, it’s the sort of visual treatment that won’t play well in movie theaters with dimmed bulbs (which is far too many these days). Still, horror fans will be pleased with the practical effects throughout. The production splashes buckets of viscera onto the screen, including dismembered body parts, gooey vomit, and an elevator filled with crimson blood. This only accentuates the occasional CGI demon that clings like a spider to the ceiling and, by comparison, looks silly.

After the film’s premiere at South by Southwest last month, the critical and audience reception was mostly positive, with fans declaring the movie an improvement on the 2013 version. But for all of its technical merits and the committed cast, Evil Dead Rise never quite popped for me. Its occasional pitch-black humor proves momentary amid the otherwise self-serious tone, making the callbacks to Raimi’s films seem shoehorned in as unnecessary and ungainly fan service. It was passable when the demons chanted “Dead by dawn” in unison. But Beth, a wholly earnest character, never earns the “Come get some” in the finale. Moreover, her arcs of self-doubt about motherhood and desire to validate her tech skills as more than a roadie have dull, writerly payoffs. The result is an awkward marriage of Cronin’s dour tone and a half-hearted attempt to approximate Raimi’s style. Though fittingly shocking and gristly, it never feels like an Evil Dead movie, but it’s not something entirely new either.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review