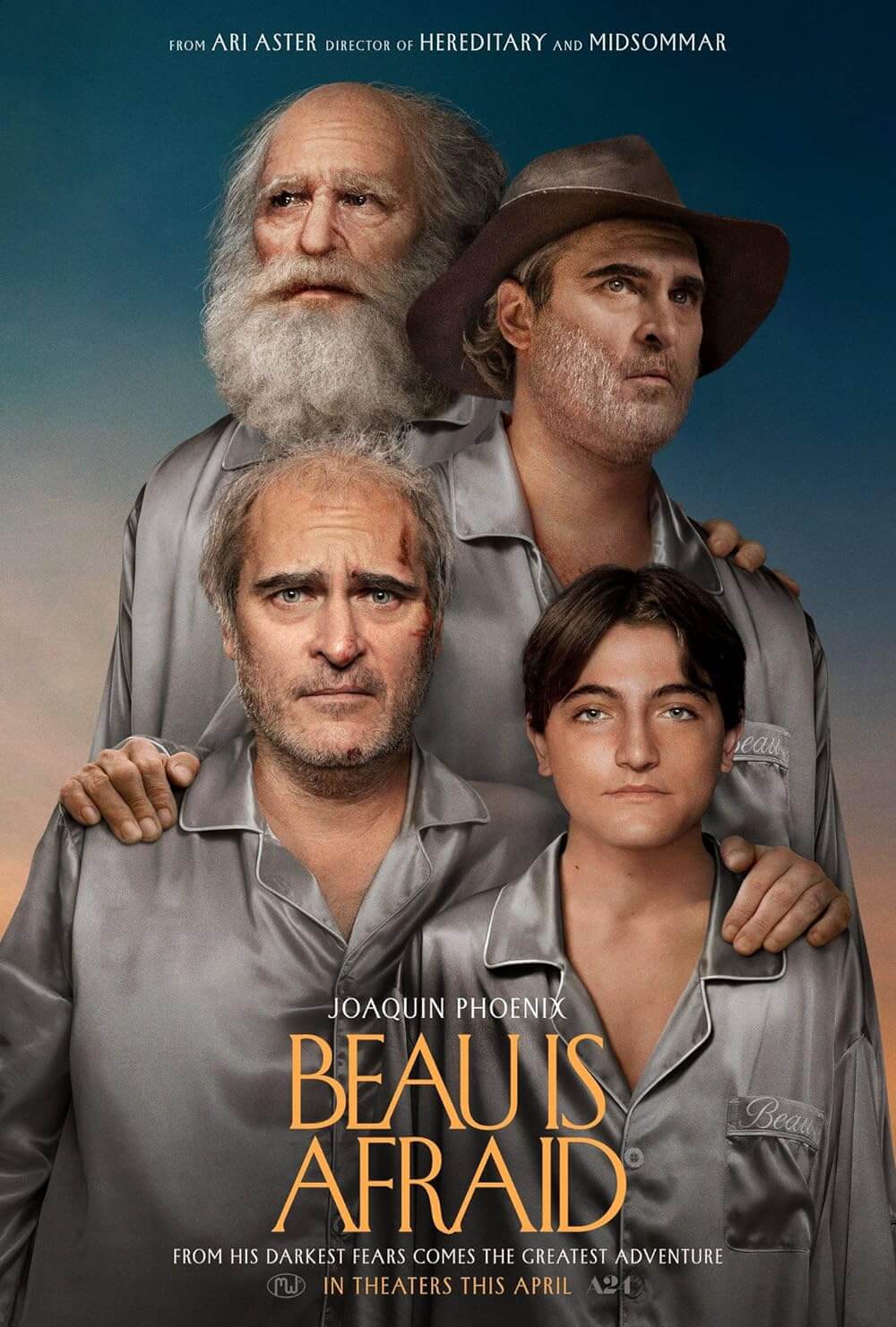

Beau Is Afraid

By Brian Eggert |

In Beau’s bathroom, there’s a small picture of a woman holding her infant child face-to-face. Writer-director Ari Aster returns to this motif in Beau Is Afraid, again with a small knick-knack that Beau intends to give to his mother, on the bottom of which he inscribes, “Thank you I’m sorry I love you.” And again with a statue that towers next to his mother’s home. But if you look closely at the picture in his bathroom, the angelic figure appears to have sharp, monstrous nails supporting the baby’s head. The sight, just one of the film’s countless surreal and Freudian details, surely spilling out from the protagonist’s subconscious, is funny and disturbing. Much of Aster’s film is like that. You don’t know whether you should laugh or feel aghast by this Kafkaesque voyage into Beau’s pointedly Jewish identity. Both reactions are correct, and you’ll probably feel them simultaneously. After all, the line between comedy and horror is thin. Laughter and fear come from our essential selves; you either find something amusing or scary, or you don’t. Aster’s film might terrify you at points, and at others, it might be the most strangely hilarious Greek tragedy you’ve ever seen. However, after surviving the three-hour existential odyssey, you’ll probably have questions. For instance: What did I just watch?

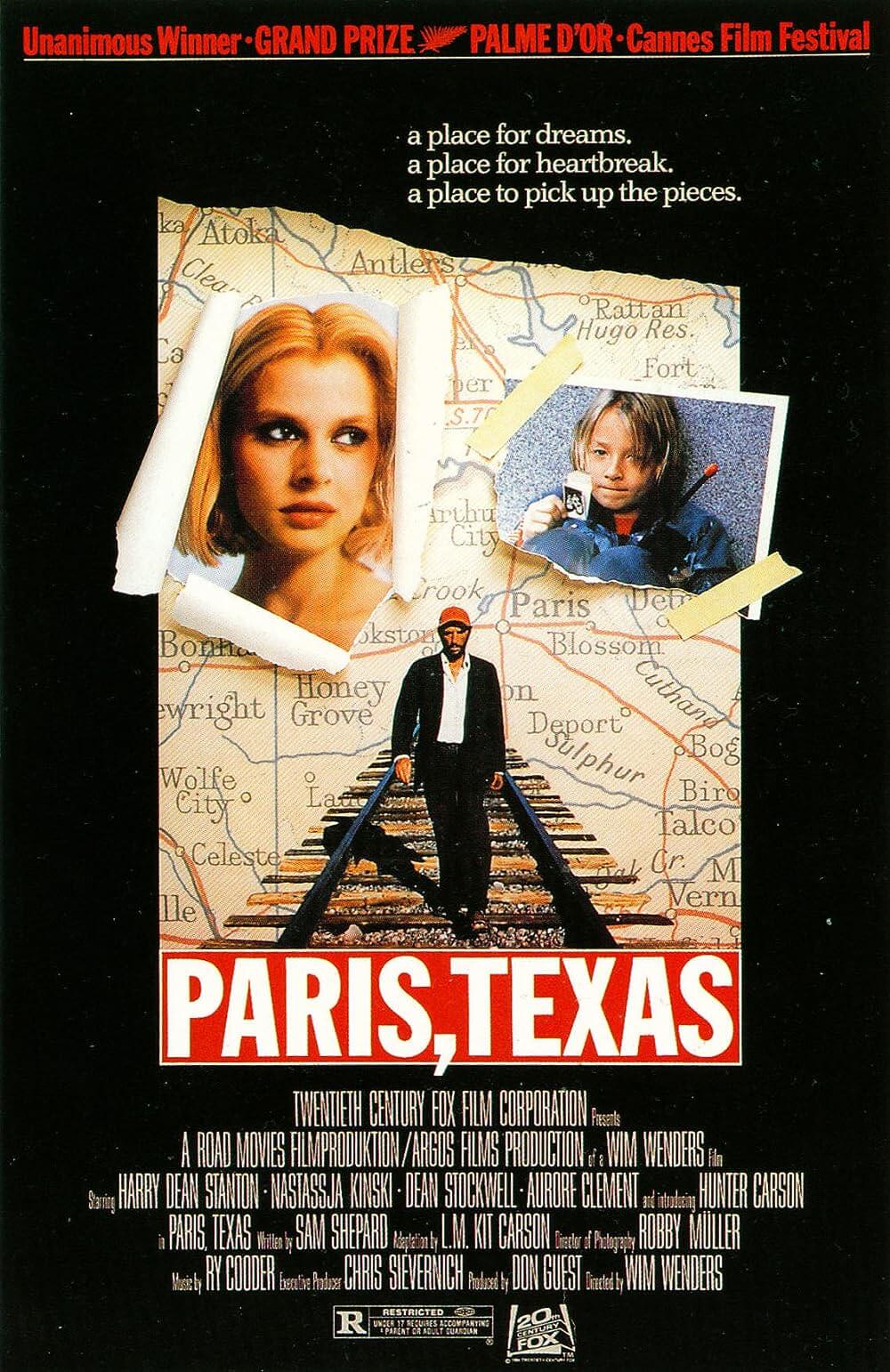

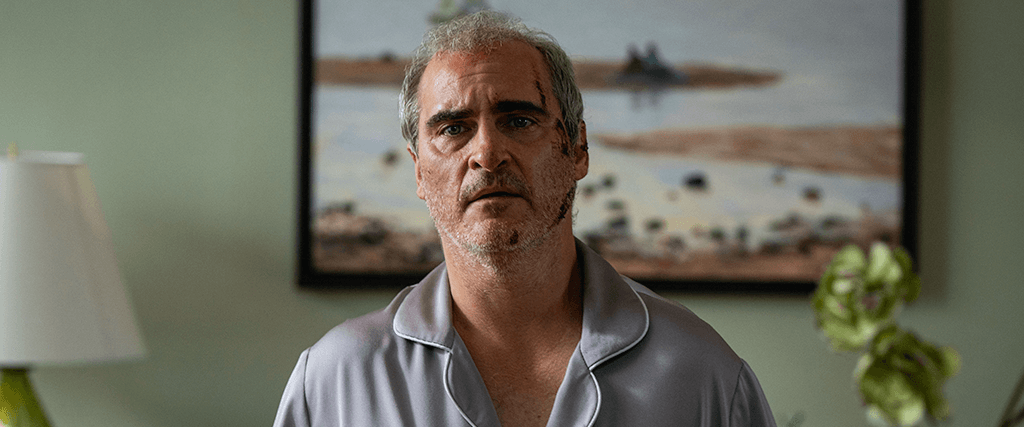

Although A24’s darling Aster started his career with jarringly emotional takes on occultist and folk horror with Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), his third and most ambitious film attempts something far less conventional. Beau Is Afraid is Aster’s delightfully self-indulgent, highly readable, and almost stream-of-consciousness epic, where the director plunges the viewer into the preoccupations and hangups of the titular character. A middle-aged man with anxiety and mommy issues, Beau (Joaquin Phoenix) was raised by his passive-aggressive mother, Mona Wassermann (Patti LuPone). She’s the guilt-tripping “superbusiness” owner of MW Industries, which distributes everything from acne cream to frozen dinners to home security solutions. Despite her continued success, Mona claims to have sacrificed all to raise her son. For this, Beau will forever be indebted to her (“Thank you I’m sorry I love you”). But Beau sees her as a smothering force. So even though she has untold wealth, he resolves to live in a shabby apartment in a dangerous city far away from her. When he plans to depart for a visit but finds himself stalled by practical circumstances, she holds him culpable, prompting the son’s desperate journey to make it right.

From the first scene depicting Beau’s traumatic birth, where his mother’s overprotective impulse finds her shouting at doctors for helping to force fluids from the baby’s airway, Aster’s film lays the groundwork for a neurotic character, immobilized by his guilt over being born. Appropriately, the next scene finds Beau, a schlubby fortysomething with graying and thinning hair, talking to his therapist (Stephen McKinley Henderson). The shrink compares his patient’s relationship to his mother with going back to a well after learning the water is poison, alluding to the crushing reproaches she uses against her son to compel his attention and fuel her own resentment. After therapy, the film follows Beau outside, into a sprawling, chaotic urban nightmare populated by a carnivalesque cross-section of humanity: a maniac with an assault rifle; the “Birthday Boy Stab Man,” who roams the streets naked and knifes anyone in his path; dead junkies; random dancers; bloodied doctors; mothers berating their children in public; and a tattooed freak who chases Beau inside. The sequence following the terrified Beau home—and most sequences throughout—features an overabundance of detail and activity, recalling Terry Gilliam’s hyperactive street scenes in The Zero Theorem (2013).

To be sure, much of Beau Is Afraid could be called Gilliamesque, including the narrative structure that closely follows Brazil (1985): Both follow an anxious protagonist, who has unresolved psychosexual tension toward his mother, and goes on a reluctant journey in a frantic and dangerous world. Trapped by his circumstances, he imagines himself as a heroic figure, loses the woman of his dreams, and ends up judged in a vast arena. If that sounds familiar, like Gilliam, Aster also seems more invested in a free association of moment-by-moment details than a forward-thrusting narrative. The filmmaker loads the frame with alternately amusing and horrifying facets, and no single sitting is enough to absorb them all. Along the way, it would be easy to lose oneself in the particulars, while as a whole, Beau Is Afraid serves as an expression of the character’s preoccupations and beleaguered frame of mind. If the film takes place in any kind of reality, it’s a heightened interpretation filtered through Beau’s irrational paranoia about the world, shaped by the trauma and rampant psychoses fostered by his manipulative mother. Then again, perhaps Mona has put her entire empire to work as an elaborate test of Beau’s devotion (the original title, Disappointment Blvd., hints at Mona’s view of her son, as well as Beau’s assessment of himself).

To be sure, much of Beau Is Afraid could be called Gilliamesque, including the narrative structure that closely follows Brazil (1985): Both follow an anxious protagonist, who has unresolved psychosexual tension toward his mother, and goes on a reluctant journey in a frantic and dangerous world. Trapped by his circumstances, he imagines himself as a heroic figure, loses the woman of his dreams, and ends up judged in a vast arena. If that sounds familiar, like Gilliam, Aster also seems more invested in a free association of moment-by-moment details than a forward-thrusting narrative. The filmmaker loads the frame with alternately amusing and horrifying facets, and no single sitting is enough to absorb them all. Along the way, it would be easy to lose oneself in the particulars, while as a whole, Beau Is Afraid serves as an expression of the character’s preoccupations and beleaguered frame of mind. If the film takes place in any kind of reality, it’s a heightened interpretation filtered through Beau’s irrational paranoia about the world, shaped by the trauma and rampant psychoses fostered by his manipulative mother. Then again, perhaps Mona has put her entire empire to work as an elaborate test of Beau’s devotion (the original title, Disappointment Blvd., hints at Mona’s view of her son, as well as Beau’s assessment of himself).

In literary terms, Aster puts Beau into conflict with his Self and his World, though his world is an extension of himself and his mother. Early in the film, Beau learns from a UPS delivery man (Bill Hader) that a chandelier has fallen on Mona’s head—she has died, horribly, and Beau must return home for the funeral across terrain fraught with dangers and detours. But he’s often crippled by his memories and dreams of his mother (the younger version played by Zoe Lister-Jones), who has implanted Beau’s deep-seated fears, including shame and terror about his sexuality. Beau’s father, Mona tells him, died at the moment of his conception. So for his entire life, Beau has avoided sex; though, since childhood, he has pined after Elaine (Julia Antonelli as a kid, Parker Posey as an adult). Moreover, during an initial chance encounter with Elaine on a cruise ship when he was a teen (played by Armen Nahapetian), he promises to “wait” for her. Most adolescents wouldn’t allow such an early romantic gesture to stall their development or sexual exploration, but Beau is an expert at finding reasons to avoid having new experiences, even if he remains a virgin into middle age. Still, he wishes for more, as evidenced by an interlude with a forest theater troupe, where Beau dreams of himself as the hero of a conventional and storybook life—a fantastical dream in which he works on a farm, raises a family, and undergoes a long journey toward a reunion.

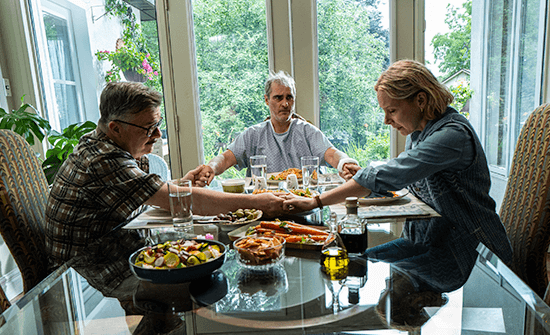

Indeed, Beau’s imagination informs the story and Aster’s filmmaking, with cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski and production designer Fiona Crombie creating an array of distinct visual chapters. The section that plays like Misery (1990), with Beau in the clutches of a psychotic couple (Nathan Lane, Amy Ryan) and their “asshole” teen daughter (Kylie Rogers), looks like a suburban nightmare—complete with Ryan as a fearful wife and Lane as an outwardly chummy, “M’dude”-spouting surgeon. Elsewhere, Beau’s stagelike fantasy of himself as a hero, a gorgeous 20-minute sequence by Chilean animators Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León, looks like a living cutout of stage decorations or a pop-up book. A later, nightmarish scene features a giant penis monster with insect-like arms—a representation of Beau’s father, or perhaps a manifestation of Beau’s sexual anxieties—that attacks a character in a scene recalling one from Starship Troopers (1997). Aster throws everything at the screen. But no matter how weird Beau’s self-flagellating projections become, Pogorzelski captures them with smooth camera movements and constant visual inspiration. Even if you have no idea what’s happening or why, it’s difficult to argue with Aster’s assured filmmaking.

Beau Is Afraid keeps the audience on edge, unable to resolve any particular moment because the entire film is steeped in Beau’s intensified worldview—an amplification of the world today. Every interaction with another human being is a stressor for Beau, as though everyone’s out to get him or make his life miserable. Every moment of his experience is overwhelming, as is every moment of this film. But it’s Beau’s perspective that accentuates each scene. At one point, a man falls into his bathtub (why remains unclear), prompting Beau to run screaming naked outside, where a police officer tells him to freeze, which he does. “Freeze! Don’t make me shoot!” the officer persists. Beau continues to comply, but the officer keeps telling him to freeze, escalating the situation. Is the officer really this jumpy, or is this representative of Beau’s fear of the trigger-happy police? The examples continue: The seemingly average couple who take him in after accidentally striking him with their van? They look like average neighbors but are really kidnappers intent on replacing their son, a fallen soldier. And Beau’s eventual reconnection with Elaine? It leads to an unsettling sex scene, whose Oedipal implications start with Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby” and only get more fucked up from there.

Beau Is Afraid keeps the audience on edge, unable to resolve any particular moment because the entire film is steeped in Beau’s intensified worldview—an amplification of the world today. Every interaction with another human being is a stressor for Beau, as though everyone’s out to get him or make his life miserable. Every moment of his experience is overwhelming, as is every moment of this film. But it’s Beau’s perspective that accentuates each scene. At one point, a man falls into his bathtub (why remains unclear), prompting Beau to run screaming naked outside, where a police officer tells him to freeze, which he does. “Freeze! Don’t make me shoot!” the officer persists. Beau continues to comply, but the officer keeps telling him to freeze, escalating the situation. Is the officer really this jumpy, or is this representative of Beau’s fear of the trigger-happy police? The examples continue: The seemingly average couple who take him in after accidentally striking him with their van? They look like average neighbors but are really kidnappers intent on replacing their son, a fallen soldier. And Beau’s eventual reconnection with Elaine? It leads to an unsettling sex scene, whose Oedipal implications start with Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby” and only get more fucked up from there.

By the climax (a loaded term in this context), Beau Is Afraid produces twists and gasps that viewers might have already suspected. A grim finale follows, set in a CGI stadium that registers as an overly pointed metaphor—a drumhead trial that judges Beau for his behaviors and, informed by his own guilt, condemns him. Yet, no matter how bizarre or obvious the symbolism throughout becomes, Aster conjures several terrific performances. LuPone, Lane, Ryan, and Posey are all great, of course, but the film is a showcase for Phoenix. Sporting a pair of massive prosthetic testicles and an iffy wig, Phoenix delivers what must be the most prolonged sense of exaggerated panic ever captured on film, combined with a wry sense of exhaustion and emotional uncertainty reminiscent of the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009). As other sources go, Aster also seems to draw from hints of the comedy of Albert Brooks’ Mother (1996) and the self-reflexive mind-bending of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York (2008).

Admittedly, I tend to love films like Beau Is Afraid, which follow no conventional or formulaic structure and jam-pack the screen with stimuli, ranging from riotous background details aplenty to shocking violence to absurdism. Films like this defy established precepts and genre limitations, challenging the viewer to figure them out rather than spoon-feeding them more of the same. You know you’re watching something special when there are as many people walking out and exclaiming aloud (“What the fuck?!”) as there were in my screening. But it’s not unfamiliar territory for Aster, whose early, expressive, and silent short film, “Munchausen,” was about a clingy mother trying to prevent her son from leaving for college. Hereditary, too, features Toni Collette’s obsessive and overbearing mother, who was quick to remind her children about her sacrifice for their benefit. Aster’s interest in unhealthy mothers raises some questions about what his relationship with his mother is like. But whatever he’s working through with Beau Is Afraid, Aster’s unmistakable personal vision is on display and, refreshingly, leaves much to interpretation and much to be appreciated. It’s neither a bona fide masterpiece nor a “career killer,” as some have argued. However, it’s a singular piece of filmmaking that deserves to be admired for existing at all.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review