Chevalier

By Brian Eggert |

This film was screened at the 42nd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. For the full lineup of films available between April 13-27, check out the schedule here. The film arrives in theaters on Friday, April 21.

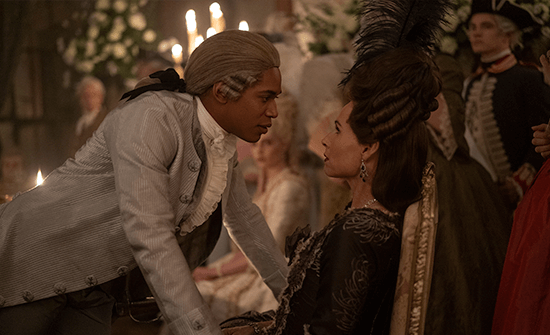

The opening scene of Chevalier finds a smarmy Mozart (Joseph Prowen) leading an orchestra and giving a solo violin performance to an enrapt audience. Echoing the production of Miloš Forman’s multi-Oscar-winning Amadeus (1984), complete with spaces illuminated by candlelight and characters speaking with English accents, the film looks like a conventional Hollywood historical drama. But then, the familiar setting is interrupted by the arrival of Joseph Bologne (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), a man of color who approaches the stage and suggests a veritable duel of violins. Incredulous, the sarcastic Mozart invites Bologne on stage, calling him a “dark stranger” with a bemused expression. But Mozart soon finds himself out-played in the ensuing performance, with his audience and orchestra favoring Bologne. Though fictionalized, the scene symbolically defies simplistic historical views of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, which often refer to him as “Black Mozart” and refuse to consider the man for his individuality. It also establishes Bologne in contrast to white European composers who make up the classical music canon, and Chevalier as an alternative to their conventional representation in cinema.

Joseph Bologne is ripe for rediscovery. Born in the mid-eighteenth century on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, then a French colony, he was the illegitimate son of a wealthy French businessman and an enslaved Senegalese woman. A child prodigy at the violin, he was raised free and trained at a private school among rich white kids. But he earned the respect of many contemporaries, given his knack for fencing, poetry, and music, rising to the honorable rank of Chevalier, despite the Code Noir that robbed people of color of their freedom in France. Bologne remains an obscure historical figure because his work was actively suppressed and destroyed in later years after Napoleon reinstated slavery, leaving all but one of his operas lost to time. But in his heyday, books and plays were written about him; he was a court celebrity, later earning notoriety for heading an all-Black regiment during the French Revolution. Chevalier’s screenplay by Stefani Robinson offers brief glimpses of his early and late life, concentrating on a period when he hoped to lead the Paris Opera.

Having earned the attention of the flighty Marie Antoinette (Lucy Boynton), who bestows Bologne with his Chevalier title after watching him win a fencing duel, our hero engages in another brash stand-off with his smug rival, Christoph Gluck (Henry Lloyd-Hughes), for the honor of running the Paris Opera. Both are charged with auditioning an opera, and Bologne wants a fresh new face as his lead. He rebuffs the longstanding diva, La Guimard (Minnie Driver), who takes his rejection of her sexual advances personally, and instead sets his sights on Marie-Josephine (Samara Weaving). An untested singer who draws his gaze, Marie-Josephine is married to the throne’s most fervent military defender, Marquis de Montalembert (Marton Csokas). Inevitably, Bologne and Marie-Josephine engage in a forbidden affair while preparing his first opera, Ernestine, some of which survives today. The only opera that remains in its entirety is The Anonymous Lover, based on a play by Madame de Genlis, here shown to be Bologne’s friend and backer, played by Sian Clifford.

Directed by Stephen Williams, the film deploys not-so-subtle anachronisms and historical liberties to render the costume drama relatable for modern-day viewers. But it’s not obvious enough to call Chevalier postmodern—at least, not in the manner of Broadway’s Hamilton or the relatively more nuanced flourishes in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006). For instance, each of Weaving’s larger-than-life expressions registers as a twenty-first-century gesture. Harrison, excellent in Luce (2019), also has a bold and daring presence that, quite appropriately for the film’s themes, feels outside of this historical period. While Williams’ direction cannot be called nuanced, he nonetheless underscores how Bologne was a man caught between worlds and, therein, a natural revolutionary. To be sure, after his mother (Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo) arrives to live with him, she and others from the Black community laugh at him, saying, “You look like a white boy” and calling him a “tourist.” After all, white society will never fully accept him due to France’s Code Noir.

Directed by Stephen Williams, the film deploys not-so-subtle anachronisms and historical liberties to render the costume drama relatable for modern-day viewers. But it’s not obvious enough to call Chevalier postmodern—at least, not in the manner of Broadway’s Hamilton or the relatively more nuanced flourishes in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006). For instance, each of Weaving’s larger-than-life expressions registers as a twenty-first-century gesture. Harrison, excellent in Luce (2019), also has a bold and daring presence that, quite appropriately for the film’s themes, feels outside of this historical period. While Williams’ direction cannot be called nuanced, he nonetheless underscores how Bologne was a man caught between worlds and, therein, a natural revolutionary. To be sure, after his mother (Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo) arrives to live with him, she and others from the Black community laugh at him, saying, “You look like a white boy” and calling him a “tourist.” After all, white society will never fully accept him due to France’s Code Noir.

Williams has spent most of his career in television, with credits including Lost, The Walking Dead, and HBO’s Watchmen. Chevalier marks his first major feature production, and it comes off elegantly. Accompanied by cinematographer Jess Hall, whose camera glides, following characters through French salons, opera stages, and drawing rooms in a manner recalling Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), Williams delivers a handsome production. John Axelrad’s editing creates digitally bridged sequences that smooth out the abrupt cuts of a montage, making for a fluid visual experience. Oliver Garcia’s costume design recreates convincing gowns and wigs. Elsewhere, the lazy writing distracts. Take when Montalembert disparages art, citing his disdain for paintings of flowers and ponds. It’s probably a reference to Claude Monet, but Monet wouldn’t be born for another 50 years. Not that anyone should watch Chevalier, or any period drama for that matter, as a work of history rather than dramatic entertainment, but some choices are bound to nag at those with knowledge of the period.

Bologne is a decidedly modern figure, setting down his powdered wig in the finale to embrace his mother’s culture with braids. Then he tells the Queen, “Not everything is about you people—that’s the point.” However heavy-handed the film can be about characters who telegraph its themes through their overstated dialogue, the sense of revolution and inclusive history remains impassioned. Even the title indicates a meaningless station with no real power behind it for Bologne, bringing to mind empty progress for people of color in lieu of true equality. Just as these themes begin to engulf the setting, the film ends far too soon, leaving the viewer wanting more about Bologne’s life during the French Revolution. Fortunately, Chevalier is likely to inspire viewers to learn more (hopefully from a book and not, you know, Wikipedia). In its current state, this is underrepresented subject matter presented in a mostly conventional format, and it will probably do some good as an introduction to a sidelined historical figure.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review